Tonight at 8pm CET, Olivier Assayas will present his State of Cinema, titled ‘Cinema in the Present Tense’, via a stream on Sabzian. Watch it here!

In 2018, by analogy with similar initiatives in other art forms, Sabzian created a new yearly tradition: Sabzian invites a guest to write a State of Cinema and to choose a film that connects to it. This way, once a year, the art of film is held against the light: a speech that challenges cinema, calls it to account, points the way or refuses to define it, puts it to the test and on the line, summons or embraces it, praises or curses it. A plea, a declaration, a manifest, a programme, a testimony, a letter, an apologia or maybe even an indictment. In any case, a call to think about what cinema means, could mean or should mean today.

Due to the corona pandemic, the State of Cinema’s third edition, which was originally planned on Friday 27 March at Cinema Palace in Brussels,1 could not take place. This event will now be replaced by a stream in which Assayas will present his State of Cinema to a worldwide audience, free of charge.

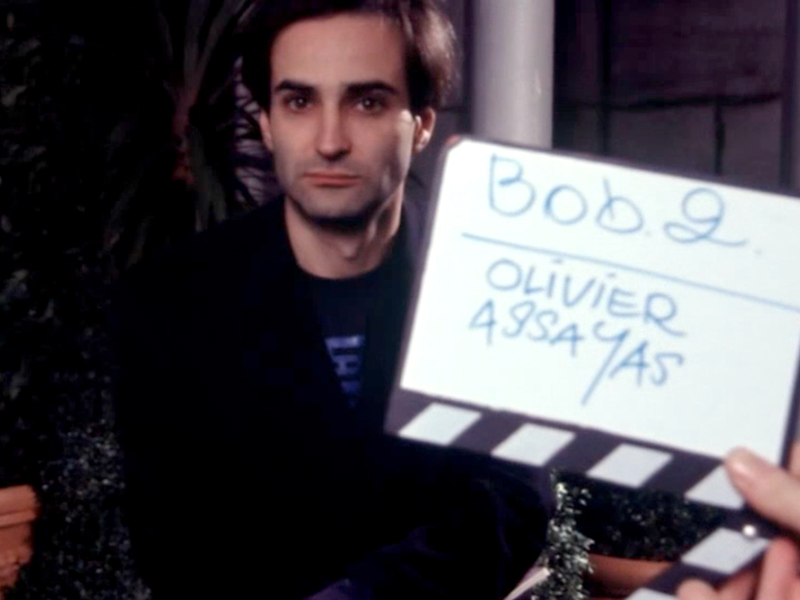

Olivier Assayas is one of the big names of French cinema. A heir to the Nouvelle Vague, he is developing an impressive and eclectic oeuvre, both generationally and geopolitically oriented, introspective and distinctly cinephile. Assayas has made sixteen feature films, including Disorder, Irma Vep, Sentimental Destinies, Carlos, Something in the Air and Personal Shopper. He has made documentaries and short films, and has written screenplays for filmmakers such as André Techiné and Roman Polanski. He has also published several books on cinema, including a book of Ingmar Bergman interviews and a tribute to Kenneth Anger.

In his text ‘Cinema in the Present Tense’, Assayas reflects on the contemporary state of cinephilia, on the position and the importance of reflection and how reflection is inextricably and historically bound up with cinema and the practice of filmmaking. We cordially invite everyone to experience this online edition together on www.sabzian.be.

On the occasion of the State of Cinema 2020, Sabzian will publish several articles by and on Olivier Assayas in the coming weeks. You can find the published texts here.

- 1Olivier Assayas had chosen Tarkovsky’s The Mirror to accompany his lecture. Sadly, due to the present circumstances, the screening cannot take place. Ticketholders of the event on 27 March can ask for a refund by sending an email to info@cinema-palace.be.

On 1 July 2020, Lumière will re-release a restored version of The Mirror in Belgian theatres.