Cinema of Circumstances

On Justine Triet’s Anatomie d’une chute (2023)

Un grand film – such is French critics’ catty formula for films that combine a weighty theme with a grandiose cinematic gesture. The type has indelibly inflected Cannes’s recent record of Golden Palms: Ruben Östlund’s Triangle of Sadness (2022), Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite (2020), Ken Loach’s I, Daniel Blake (2019). Anatomie d’une chute, the 2023 Palme d’Or-winning courtroom drama from the French director Justine Triet, also keeps itself at the beck and call of its viewers and critics, albeit without openly indulging the social themes of its predecessors. In an era in which gender issues are increasingly subject to public theorising, Anatomie focuses on shifting patterns in the relationships between men and women as part of a broader sociological investigation.

Anatomie narrates the parable of a contemporary middle-class couple. An international family consisting of Sandra Voyter (Germany), Samuel Maleski (France) and their visually impaired eleven-year-old son Daniel inhabit a house in the mountains not far from Grenoble. They live in a residence built by the father, after both parents’ careers in the metropolis. Returning from a walk with his guide dog, Daniel stumbles upon his father’s body in front of the family chalet, face motionless in the snow. It is unclear at first whether Daniel has run into a murder, suicide or accident; soon, however, Sandra is both cast and charged as the primary suspect. The evidence is sparse and fraught with ambiguity; in the absence of witnesses, the relationship between Samuel and Sandra is dissected to the bone.

This process unearths a venomous relationship, marked by Samuel’s professional and sexual jealousies, and Sandra’s casual infidelities. She is a well-known writer causing furore in literary circles with her heavily confessional novels mixing private experience with elements of fantasy – an exponent of autofiction. A middling academic, Samuel has been plodding on his debut novel for years, a project hampered by both individual inertia and the success of his partner. His psychiatrist tells the court that he thinks Sandra figuratively “castrated” him. Sandra, for her part, repeatedly cheated on her husband, especially with women; in the opening scene, Daniel disrupts a meeting between her and a younger female postgraduate.

During the trial Samuel also emerges as a man burdened with a paralysing guilt complex. This mainly concerns the accident that left Daniel visually impaired at the age of four, at a time when the child was in Samuel’s care. For her part, originally German-speaking, Sandra regrets exchanging a lively London scene for a forest chalet close to Samuel’s hometown. This mutual resentment finds expression in a sequence of heated arguments, the last of which takes place a day before Samuel’s death – and is later found to have been recorded by Samuel himself. In the courtroom, the young Daniel faces a wall of parental envy. Unwillingly, he is coaxed into the role of the trial’s main witness, forced to choose between the ghost of his father and a surviving mother. As the oedipal subject, he will deliver his parents’ verdict – and ultimately his own.

Anatomie is hardly shy about its quality labels. Triet’s cinematography combines the techniques of the auteur and television film, resulting in a more than two-hour-long exercise in haute vulgarisation. Triet’s dramaturgy is confusingly classical: each component of the whodunnit and crime story is handed to viewers almost menu-wise, from flashback to voice-over to arguments about forensics. Triet’s film exhibits little shame about the recognisability of those templates and props: Anatomie opens as a crime series, where familiar attributes – a bird’s-eye view of the corpse in the snow, the out-of-focus portrayal of the fatal leap, the patient reconstruction of the crime – merge into the more abstract reflection that Triet is after: not just the anatomy of “a” fall, but her treatment of the general Fall (of the family, relationship, man, male sex).

These intentions become manifest in the opening sequence of the film, in which spectators are treated to an instrumental rendition of 50 Cent’s ‘P.I.M.P.’ reverberating through Samuel’s mountain cabin. The soundtrack’s high volume betrays its hyperbolic function: the track blares through both the scene and the cinema, resulting in an overwhelming tangibility. As an instance of cinematic action painting, Triet seeks out a sense of immersion: not only the cinematic forms but the film’s texture is brought to appear, thus promoting viewers as witnesses to the incident.

From its opening minutes, Triet thereby plays in two registers: Anatomie remains viewer friendly, but its participatory ethos upgrades it to something more than the passive, weekday flick. Indeed, the film’s play with genre codes and conventions assists the director’s grand gesture, including Triet’s reflection on three bourgeois institutions in clear crisis: family, novel, law. The director attempts to defuse the dislocation of these with her fourth institution: the feature film.

Viewed from this angle, Triet’s choice for a fiction film also becomes intelligible. Anatomie patiently homes in on contemporary neuroses around truth and truthfulness, more specifically the fading distinction between fantasy and reality in a digital world. Through the genre of a family drama, a broader point is made about the contemporary crisis of representation in the legal system, marital life, and the world of the novel. More than a mere film treatise about gender relations, like David Fincher’s Gone Girl (2014), a socio-aesthetic argument is being delivered; more than any recent crime and courtroom drama, the same gendered theme comes to the fore during the trial in Anatomie.

This might suggest a rather probing sociological inquiry, but in Triet’s case viewers need not look too far. The director has admitted to being inspired by the case of Amanda Knox, who was accused of murdering her British roommate Meredith Kercher in Italy in 2007 (Knox was eventually acquitted). Knox’s trial provided fodder for a feature film and a popular Netflix documentary. Both exemplify the true-crime boom marking recent years: the (re)investigation of cold cases on which viewers are asked to pass final judgment. The trial by media is here reworked as an aesthetic format. As with Sandra’s works of autofiction, the popular genre consistently draws its collateral from reality: works of fiction must not only persuade but also render truthful, producing a tissue of deeply contemporary confusions: was Knox guilty or not? Was the killer found at the end? Questions of strict legal guilt here become casually relative; characters exist to spin the mill of rumours.

Anatomie thematises the same confusion to its advantage. The three institutions the film dissects once had clear prescriptive rules; Triet now demonstrates how their spaces have become interspersed. The viva voce transcript of the marital argument in the courtroom transforms the sequence into an audio play, in which the spouses, as if they were actors appearing on a stage, hurl lines of dialogue at each other; Sandra’s latest novel is set in reverse, staged as evidence in the case; her novellas, so we are told, are not mere instances of fiction, but contain hard nuclei of “truth”; mum and dad’s multilingualism illustrates a communicative bind afflicting every contemporary relationship.

Disorder then manifests itself at each of Triet’s levels. The legal system once represented a world in which the personalities of both spouses remained outside of the picture. Now a second, parallel media circuit intrudes, in which procedural patience has no place. In Triet’s film, a court of law stands out as a space spawning its own fictions, an arena with its own rhetoric, actors and audience looking directly onto the street. Nor does the film’s plot focus on factual truth-telling; the judicial investigation and police detectives are conspicuously absent from Triet’s account. What, then, is her trial about? The distillation of a believable story, so it seems: the prosecution must portray Sandra as a ruthless careerist fed up with Samuel’s ceaseless self-pitying, only to end up defenestrating him. The defence, in turn, underscores Samuel’s essential superfluity, a man cut down to size. The rules of the true-crime format are loyally abided by: it is not up to jurors to judge Sandra, but instead to the audience itself – who will demarcate fact from fiction.

Viewers are even invited to render judgment on family matters. As a modern woman, Sandra not only eagerly takes part in the job market and coerces her husband into home-schooling their son but also effortlessly outclasses him on the professional front. At the end of the film, Daniel, like a blind Tiresias, seems to put a confession into his father’s mouth: father committed suicide. A voice-over with Daniel’s voice dubs the lips of his sire; the boy now commits symbolic parricide. That coup d’état is still possible, even within a relationship in an age after emancipation. Officially, women and men today meet as equals in the labour and partner market. The free-spirited middle class in which Sandra and Samuel move has no distinct expectations about the roles a wife and husband should fill. Anatomie debunks the myth of linear liberation and unearths a hybrid of hypocrisy and transparency. Can Samuel share his life with a successful woman? Does Sandra answer to the maternal ideal? Is Samuel capable of accepting Sandra’s adultery? Was Sandra guilty of psychological castration? Did she facilitate Samuel’s impotence? By cheating on him with women, did she terminally disable her husband’s libido?

A society without shared codes seems to generate unpredictable new codes. An older bourgeois tension between public and private remains unresolved. Sandra’s novelistic genre was once the preferred instrument against this dislocation. “The great bourgeois form of literature”, as Walter Benjamin once described the novel, the “aesthetic centre of gravity that embodied the self-confidence of the middle class as a whole.” In Hegel’s view, modern man was confronted with a “reality already ordered into prose”, for which the novel became the medium of choice, reconciling the “conflict between the poetry of the heart and the opposing prose of circumstances.”1

Hegel’s tension will no doubt seem familiar to contemporary viewers. The hangovers of feminism’s great age of emancipation are now a grateful theme for many a feminist critic on both the left and the right; so is the crisis of the novel incarnated by Sandra. In that general atmosphere of critique, Triet’s project certainly appears to thrive – her very own poetic treatment of a new prosaic reality.

Whether Anatomie is up to this translational exercise is another question. Despite its critical theory and templates, Triet all too often seems to fall victim to her own quest for recognisability: a gentrified television film cannot easily transcend the bounds of its genre. An earnest interest in the film’s core subject, the middle class, is difficult to discern, as is the question of how that class can be identified today. Nor are viewers offered anything dramatically new about how gender relations have shifted in Sandra and Samuel’s circles. Topoi like the sapphic feminist and the splenetic macho remain in its stead, with the manoeuvres of the detective story as a cheerful add-on: who done it, endless disputations about evidence.

In strict accounting terms, Triet’s project has an undeniable plausibility – all the elements of the grand film draw present. In a 1961 conversation in Cahiers du Cinéma, however, the French director Jacques Rivette vehemently objected to a view of films as somehow consisting of neatly additive components – “that this or that film has a neat screenplay, that the mise-en-scène is only so-so, that the editing, on the other hand, is brilliant, that the music is dull, the sets hideous: I think that’s completely beside the point [...] One cannot oppose content to technique; every film consists of a unique expression, and if the film is successful, this expression will form an integral whole.”2 Despite a neatly ticked-off checklist and grand critical ambitions, Anatomie teeters on precisely Rivette’s criterion: Triet stages a shadow play in which many an “issue” is raised but corollary questions are never explored, as if viewers were witnessing a cross-examination delivered in bombastic sign language. A family film that can only engage with its object by deploying clichés will end up as little more than a flashy family film – in this case, one that also reveals pitifully little about the institution it purports to describe.

- 1David Cunningham, “Capitalist Epics,” Radical Philosophy, September-October 2010.

- 2Morvan Lebesque, Pierre Marcabru, Jacques Rivette, Eric Rohmer and Georges Sadoul, “Débat,” Cahiers du Cinéma, December 1961.

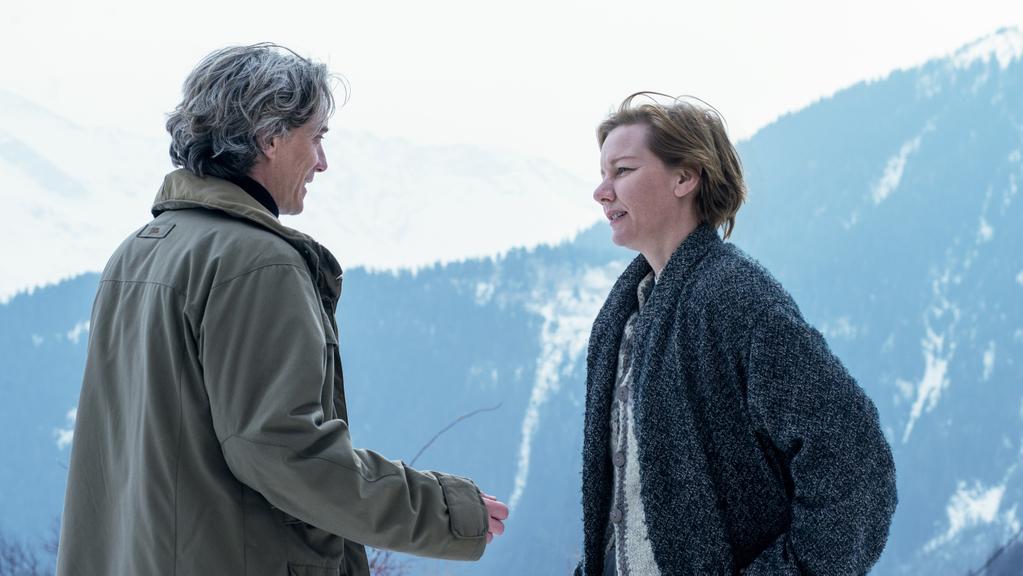

Images from Anatomie d’une chute (Justine Triet, 2023)