The Knokke Cinema

One could hold against me that the following has only a very remote connection with the individual films shown in Knokke1 and that it is a postulate rather than a description of reality. Well, that is how it is intended, not as some far-fetched defence of everything that was shown in Knokke. I would not be able to judge these films in any meaningful way: a regular moviegoer so rarely comes into contact with this genre that its strangeness alone is initially confusing. The devotees of this kind of films are mainly the people making them. Reliable criteria for judging them have not been developed, let alone a theory.

Instead of considering the complete otherness of these films, one often heard in Knokke the convenient excuse that an experimental film festival, by definition, has the right to show failure and imperfection, because these films are primarily about testing new forms and materials which do not necessarily have to be meaningfully integrated into a whole. This argument presupposes that the makers of these films see themselves as suppliers to the commercial film industry. The common premise of all these films, however, is that they consciously oppose narrative cinema, which in the minds of most people is the only cinema. These films are only undetermined when measured against the categories of narrative cinema. To demand that individual works be self-contained would be to misunderstand their basic tenor.

The impression that the filmmakers at Knokke are mainly concerned with form, with testing the technical possibilities of cinema, only stems from the fact that we are used to orienting our reflections on cinema exclusively towards films whose narrative forms ultimately derive from the repertory of the realistic novel. They are indeed concerned with forms and materials but also with the uncovering of the elementary means of expression of cinema and the discovery of the expression that is intimately linked to these forms. The New Cinema, which developed under the sign of Neorealism and the Nouvelle Vague after 1945, turned against the unconscious use of narrative forms; the Knokke cinema is against this kind of film altogether.

The absence of French films of interest in Knokke was symptomatic and the absence of the critics of the Cahiers du Cinéma at least remarkable. Neither of these should be overstated, but both facts are significant when trying to understand the place of the Knokke cinema in film history. The Cahiers and the innovators of French cinema who emerged from their ranks discovered American film for us in Europe and made it more comprehensible. What fascinated them about American cinema were its direct, naïve forms, without the didactic pretence with which European cinema was burdened. The only thing is that, upon its reception by Europe, this cinema lost its purity and naïveté, on the one hand because one was never particularly interested in the relation between the film forms and American life and on the other hand because these American discoveries were only fully endorsed after already being converted into important components of film culture in academic terms. The Knokke cinema stands against this very Hollywood-style American cinema. It is only logical that it developed most where Hollywood’s pressure is greatest, namely in America. America was best represented in Knokke. And should an attentive French admirer of American cinema have been present, he would certainly have been green with envy at some of the new American films, because for all their structural differences from Hollywood cinema, they still have one thing in common: an absolutely natural relationship to their medium, a far cry from any cultural babble.

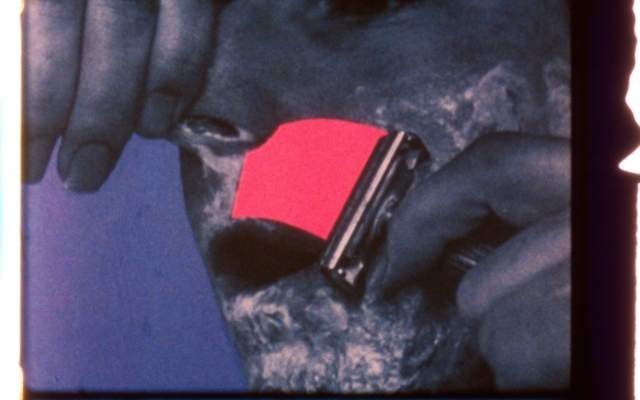

In the autumn of 1960, the New American Cinema Group issued its first manifesto, which concluded with the following sentences: “We are not only for the new cinema: we are also for the New Man [...] We are for art, but not at the expense of life. We don’t want false, polished, slick films – we prefer them rough, unpolished, but alive; we don’t want rosy films – we want them the color of blood.” Such demands for a more vital relationship between art and life have been made at least since Surrealism. The tradition the New American Cinema ties in with is a European one. Its role models are the film avant-gardists of the 1930s. Just as young Americans today feel enthusiasm for a film language free of sediments of other media, which thanks to their specific capacities are capable of direct expression, so Antonin Artaud already celebrated the “fast and direct language” of cinema which would finally put an end to the absolute rule of analytical intelligence, language and writing: “The advent of cinema coincides with a turning point in human thought, with the very moment when language is exhausted and loses its symbolic power, when the mind is tired of the game of representations. Clear thinking is not enough for us. It defines a world that has been exhausted to the point of evil. What is clear, is immediately accessible, but what is immediately accessible serves as a shell for life. Slowly it becomes apparent that this all-too-familiar life is not all of life.”

What struck the eye as common to the more important films at Knokke was not only the rejection of the usual narrative cinema but – even more decisively – the rejection of figurative cinema, the cinema of representation that depicts the world according to the possibilities of human receptivity. They used the technical means of cinema to show life under the familiar shell Artaud speaks of. They dissected the familiar surface into shapes and colours, revealing grids under the everyday, undermining the sense of time, that is, they destroyed what is considered real time in favour of another, which could perhaps be called the physiological time of each spectator.

When Pasolini tried to describe poetic cinema, he defined it in contrast with prose cinema as a cinema of visual communication whose instruments were raw and instinctive, stemming from a prehuman, pregrammatical and premorphological order. When Pasolini wrote this, he would hardly have been thinking of films like those at Knokke, but they exactly meet the demands Pasolini makes on such films. Compared to the usual narrative cinema, they are like poetry to other literary genres. Just as poetry, through the novel use of all the components of prose, helps language to ever new expressive possibilities, so this cinema finds means to represent the unknown of the world around us through the mere contemplation and the novel use of the elementary means of cinema. If one considers how fast the number of followers of this cinema has grown in America in recent years, how well the organisations founded to distribute these films are working, how great the interest of young people in this type of film was at Knokke, one can only wonder how this cinema has remained unnoticed by cinephiles.

In a recent interview, the eminent linguist Roman Jakobson, co-founder of the Russian Formalist School, was asked why scholars and poets of the group had made poetry the central focus of their interest. His answer is not only a kind of justification of the Knokke cinema, it could also point the way for future reflection and research on non-narrative film. He said that poetry is so perfectly suited to exploring the possibilities of language because it is the clearest way to study the finalism of language, the connection between the means used and the intended effect.

The extent to which the discoveries of linguistics have changed our lives seems to be penetrating the public consciousness only very slowly. The students who loudly demonstrated against the formalism of the festival in Knokke would probably have difficulty understanding the Russian cyberneticist Sebastian Shaumyan, who recently called these discoveries “a real revolution”. The cinema that these progressive students are calling for can hardly be more conventional. They still seem to think that all they have to do to capture an image of the world is to use the camera like Renaissance painters used a brush. Their indignation is lazy. It has no need for the special effort of thought they are insisting on. It made me think of Adorno’s famous remark that it would no longer be possible to write poetry after Auschwitz. Everyone knew what was meant by it, it sounded good, but it just wasn’t true.

- 1At the Fourth International Competition for Experimental Film, organised by the Cinematheque Royale de Belgique, 25 December 1967 – 2 January 1968.

The same Filmkritik theme issue about the Knokke cinema also included contributions by Ulrich Gregor, Peter M. Ladiges, Uwe Nettelbeck and Enno Patalas, and a Selbstanzeige [self-display] by Lutz Mommartz.

This text was originally published in Filmkritik 12, no. 2, 134th issue of the complete series (February 1968): 102-103.

Image (1) from The Big Shave (Martin Scorsese, 1967)

Image (2) from Ray Gun Virus (Paul Sharits, 1966)

Image (3) from Razor Blades (Paul Sharits, 1965-1968)

The three films were screened at the fourth edition of EXPRMNTL (25 December 1967 – 2 January 1968).