Described Film

The Film Criticism of Frieda Grafe

Six Moments

Seeing With Photographic Devices

Spiritual Gentlemen and Natural Ladies

Zéro de conduite and L’Atalante by Jean Vigo

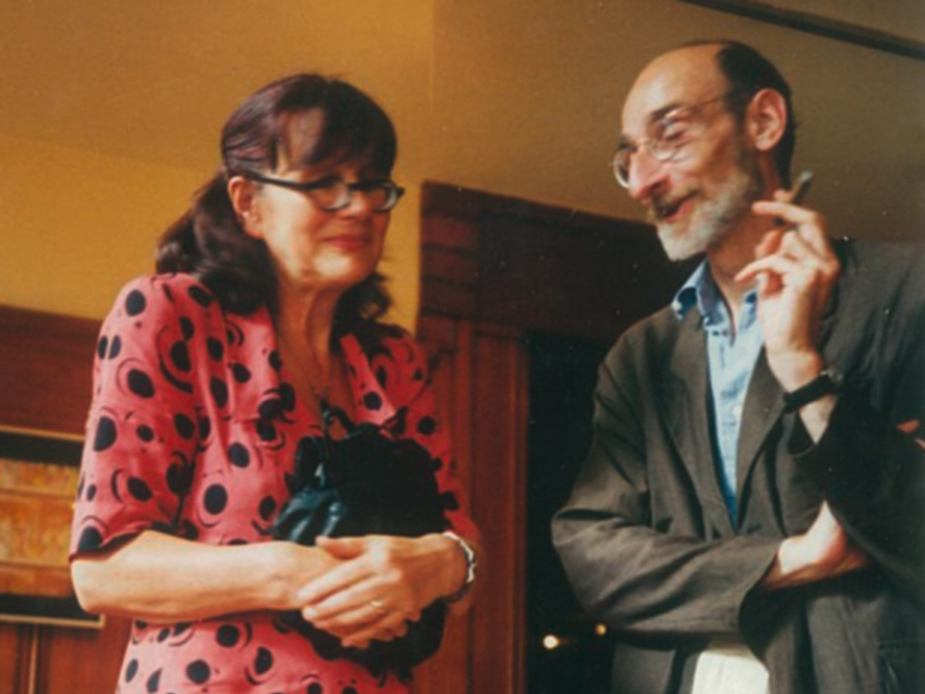

Frieda Grafe (1934-2002), the “Königin der deutschen Filmpublizistik”, began her career in 1962 with the monthly journal Filmkritik, the flagship of the still-young German film criticism. She would go on to publish around 120 pieces there. From the early 1970s onward, Grafe primarily published in the weekly Die Zeit and the daily Süddeutsche Zeitung. She contributed to monographs on Fritz Lang, F. W. Murnau, and Ernst Lubitsch, and she translated books by and about Alfred Hitchcock, François Truffaut, Éric Rohmer, Jean-Luc Godard, and Jean Renoir. She did so partly in collaboration with her husband, Enno Patalas, himself one of the most important German film historians and critics of the twentieth century, founding editor of Filmkritik, and at one point director of the Munich Film Museum.

Even during her lifetime, several collections of her writings were published. Im Off: Filmartikel (1974) brings together seventy texts by Grafe and Patalas – articles spanning a ten-year period, 1964-1974, that not only engaged readers with contemporary cinema but also argued for a more intense relationship with the films of D. W. Griffith, Erich von Stroheim, Ernst Lubitsch, and Max Ophüls. For Grafe and Patalas, these were not separate concerns. A history of cinema, they believed, should not be structured solely by the rhythm of premiere dates but must also take into account the “forgotten and suppressed aspects of official (film) policy.” Im Off collects texts that were originally published under Grafe’s own name but appear here under both their names. Grafe and Patalas had a quasi-symbiotic life and work relationship. Both emphasized how deeply their writing emerged from shared viewing experiences and conversations.

In 1985, Beschriebener Film appeared, a collection of texts Grafe mainly wrote for the Süddeutsche Zeitung. The title refers to Grafe’s own characterization of her criticism. She aptly called it “described film” because, as Irmela Schneider notes, “she avoided the critic’s gesture of the schoolmaster or judge and focused on making her way of looking at films accessible and vivid for the reader.” A way of writing that Grafe herself once described as: “I try to reconstruct the general tone of a film for the reader, based on my impressions and insights, so that they may reach their own conclusions or assumptions.”

A very different facet of her work were the Filmtips – short commentaries on Munich’s film offerings, often just a single sentence per film – which were published weekly in the Süddeutsche Zeitung from 1970 to 1986. After her death in 2002, the publisher Verlag Brinkmann & Bose released a twelve-volume edition of her collected writings, edited by Patalas.

Grafe’s film criticism remains virtually unknown and unread outside of Germany. Until a couple of years ago, only a handful of translations had been published in English. In the late 1970s, a few translated essays were included in two BFI publications on Carl Theodor Dreyer and Max Ophüls. Later, in 1995, the BFI published a short essay on The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947) by Joseph L. Mankiewicz as a standalone booklet. In France, her work has mostly circulated via translations in the journal Trafic.

As a first step towards addressing this gap, Sabzian has coordinated a dozen newly made English translations. In ‘Realism Is Always Neo-, Sur-, Super-, Hyper-’, one of her most renowned texts, Grafe criticizes the “illogical” term “neorealism,” which suggests an absence of fiction. She observes that in the films of Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica, and Luchino Visconti, “a new reality only comes into view through a new way of perceiving.” Five texts in the selection originally appeared in Filmkritik. ‘The Knokke Cinema’ is not a classic report on the experimental film festival in Knokke. Instead, Grafe focuses on the perception of American experimental cinema. These films, through their free form, consciously position themselves against classical Hollywood cinema, but at the same time, for Grafe, they share “an absolutely natural relationship to their medium, a far cry from any cultural babble.”

For Grafe, cinema was the art form par excellence that could render the symbolic character of reality visible – because it appears to represent directly, it makes social orders and their imperatives perceptible. In Au hasard Balthazar by Robert Bresson, the story and the figure of the donkey are, above all, “a represented aesthetic fact, a means not of representing reality but of referring to it.” Again and again, her “descriptions” are linked to broader aesthetic propositions and social insights. For Grafe, Trouble in Paradise is a crime film “not only because it’s about crooks,” but because it “reveals imposture to be the essence of cinema.” In La collectionneuse, she sees how Rohmer makes literature visible, “how it relates to life.” In her text on Godard’s Vivre sa vie: “The verisimilitude of his art does not rest on faithful imitation of reality but manifests itself in the recognition of its fictional character.”

The four texts originally written for the Süddeutsche Zeitung also make clear that cinema, for Grafe, is above all a world of forms. “Dreyer brings forms into view that make clear the underlying structures that generate them,” she wrote about the Danish filmmaker. It is precisely these forms that make reality visible. In her piece on Jean Vigo, she lets the French filmmaker affirm this himself: “Our senses are not keen enough to see the flow of events; we need forms because we cannot grasp the subtlety of absolute movement.”

In 1970, together with Patalas, she criticized the anaemic relationship between (German) television and film art. Due to its inability to explore its own medial reality, television merely “appropriates film history in order to exploit and rehash it.” Three years later, Grafe posed a question in the German daily: “How to orient yourself in Ozu films?” She sees Ozu as a Zen filmmaker who compels the viewer to abandon “the usual search for the meaning behind things” in favour of “simple, pure perception.” The text ‘Scope: Format or Ethics’ grew out of a lecture in which she examined the artistic consequences of CinemaScope. In her view, the relationship between content and form is “not of a physical but of a moral nature.”

This compilation of translations is preceded by an introductory text to Grafe’s film criticism by Volker Pantenburg, in which he recalls “six ‘Frieda Grafe moments’ – instances and sentences which reveal some of the many qualities of her writing and thinking.” The dossier concludes with ‘For Frieda’, a short tribute by Eric de Kuyper, Belgian filmmaker, writer, and friend.

Gerard-Jan Claes