On 10 November, Sabzian and Beursschouwburg present five short films by the Italian filmmaker Cecilia Mangini (1927–2021) as part of its Milestones series: La canta della marane (1962), Brindisi ’65 (1966), La Briglia sul collo (1974), Stendalì: Suonano ancora (1960) and Essere donne (1965). The selection of films represented in this series, made between 1960-74, feature the many different facets of her filmmaking, as well as her textual and musical collaborations, including those with Pier Paolo Pasolini and Egisto Macchi, her long-time composer.

Born in 1927 in the southern Italian town of Mola di Bari, Mangini began her career as a photographer. She moved to Rome in 1952 and first came into contact with cinema as an organiser in the Italian federation of film clubs, where she also met her future husband and lifelong collaborator Lino Del Fra. Mangini’s debut film Ignoti alla città [Unknown to the City] (1958), a film about disaffected and alienated youths in Rome’s postwar suburbs, is considered the first documentary ever made by a woman in a very male-centric, post-fascist Italian society. The film was inspired by Pier Paolo Pasolini’s novel Ragazzi di vita [The Street Kids] (1955), which prompted her to ask him to write the commentary for her film, after finding his address in the phonebook. They would collaborate on two more of her films, with Pasolini writing the script for La canta delle marane [The Blues of the Marshes] and Stendalì: suonano ancora [Here They Play Again] (1960).

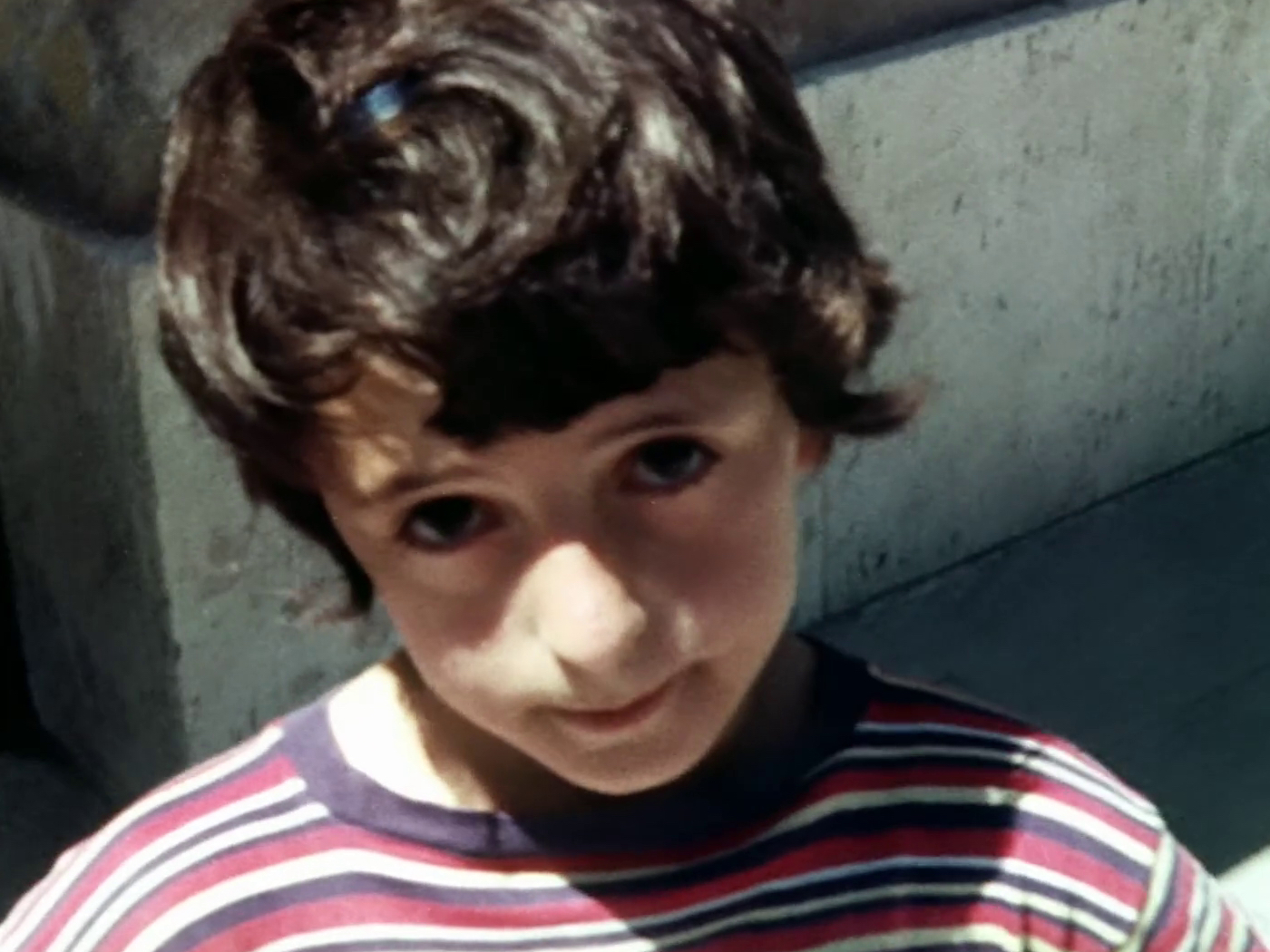

Mangini’s films penetrate deeply into post-war Italy, where social reconstruction is struggling, especially in the south, and industrialisation is creating precarious conditions in the north. In front of her camera, the daily lives of Italians living socially on the margins become both poetic and political. Their words, but especially gestures, body language and facial expressions, contain a disruptive potential revealed by Mangini’s gaze, which was clearly shaped by neorealism. Perhaps not surprisingly, the young are very often at the centre of her work. As a representation of the future of the country, they caught her interest from early on, as films like Ignoti alla città, La canta delle marane, Tommaso (1965) and La briglia sul collo [The Bridle on the Neck] (1974) clearly show.

Besides her focus on the proletariat and the fate of the young and disenfranchised, Mangini’s filmmaking is also marked by a desire to capture the often disappearing ritual performances of Italy’s southern rural communities. Inspired by the research of Italian anthropologist and philosopher Ernesto de Martino, she records religious and magical rituals, staged or otherwise. Here Stendalì serves as the strongest example, a staged recording of a traditional mourning song in Griko dialect, spoken in the region of Puglia. Gathering the last surviving performers proficient in the art of lament, who live scattered among the small villages of the Grecìa Salentina area of Puglia, she believed funeral chants to be one of the highest forms of poetry. Through her collaboration with Pasolini, who created a Griko “replica” from the only remaining memories of the song, the film helps safeguard the practice from oblivion.Her quietly confrontational documentaries of daily life in Italy were censored for many years. In Mangini’s own words, the Italian system forced documentary filmmakers to act “under the radar like drug dealers”. Driven by a strong libertarian and anarchist sense, she never shied away from pointing an accusing finger at vested political powers. Mainly for this reason, her films have only recently started to be restored and re-exhibited.1

![La canta delle marane [The Blues of the Marshes] (Cecilia Mangini, 1961) La canta delle marane [The Blues of the Marshes] (Cecilia Mangini, 1961)](/sites/default/files/la%20canta%20delle%20marane_front_0.jpg)

Milestones is a series of stand-alone screenings, hosted by Sabzian, of film-history milestones, reference works or landmarks, films that focus on aesthetic or political issues and stimulate debate and reflection. In earlier instalments, Sabzian presented Andy Warhol’s Sleep (1964), Jean-Luc Godard’s monumental video work Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988-1998), Robert Kramer’s Milestones (1974), Méditerranée (1963) and L’ordre (1973), two films by Jean-Daniel Pollet and recently Shadi Abdel Salam’s Al-mummia (1969), Georges Rouquier’s Farrebique ou les quatres saisons (1946), Al Dhakira al Khasba [Fertile Memory] (Michel Khleifi, 1980), Harun Farocki’s Bilder der Welt und Inschrift des Krieges (1989) and Losing Ground (Kathleen Collins, 1983). For each screening, Sabzian publishes texts that contextualize the film.

- 1Following the restoration of Mangini’s films by Cineteca di Bologna a series of retrospectives were held all over the world. Last year, feminist film journal Another Gaze also dedicated a dossier to her work and presented a selection of films on their platform Another Screen.