“To try and live together”

The Films of Anne-Marie Miéville

“The love experience will be reshaped into a relationship that is meant to be between one human being and another, no longer one that flows from man to woman.”

This quote from Rainer Maria Rilke, which adorns the end of Lou n’a pas dit non (1994), encapsulates the essence of Anne-Marie Miéville’s quest, which is driven by a universal, imperishable question: how to live together? The same film illustrates par excellence how her singular trajectory finds its way through art history in all its forms, from the sculpture of the mythical couple of Mars and Venus, which occupies a central place in the film, to an extensive pas de deux from Jean-Claude Gallotta’s Docteur Labus that expresses a broad palette of friction and tension between a man and a woman. Again and again, the possible relationship with another is examined as a constant field of tension between stasis and movement, between silence and speech.

Miéville’s delicate study of the challenges of communication and the trials of love is already central in her first short film, How Can I Love (a Man When I Know He Don’t Want Me) (1983), whose title is extracted from Otto Preminger’s Carmen Jones (1954). The theme of Carmen doesn’t accidentally recall Prénom Carmen (1983), a film for which Miéville herself provided the screenplay to Jean-Luc Godard, her companion in life and work since they collaborated on the film that would become Ici et ailleurs (1973-‘76). But whilst Prénom Carmen revolves around the unrequited love of a man for a woman, the roles in How Can I Love are reversed. A reversal, as Alain Bergala has remarked, that changes everything, not in the least as seen in the mise-en-scène that reflects the desire for togetherness as a permanent arena in which men more often than not shield themselves, incapable or unwilling to open up to a possible dialogue.

The figure of the man who has lost his confidence in the potential of discourse returns in Le Livre de Marie (1984-‘85), in which a marital separation is portrayed with remarkable elegance and precision from the perspective of the young daughter, who expresses her resistance to the parental drama with the help of language, music and dance. In Miéville’s first feature length film, Mon cher sujet (1988), the power of word and song is employed by three women of as many generations – grandmother, mother and daughter – to acquire a place in a world where women are expected to share everything while men tend to flee from every commitment to share. Also in her following film, Lou n’a pas dit non, it’s the woman who, by exploring various forms of expression and creation, paves the way for a possible exchange, in a perpetual movement of approach, confrontation and reconciliation.

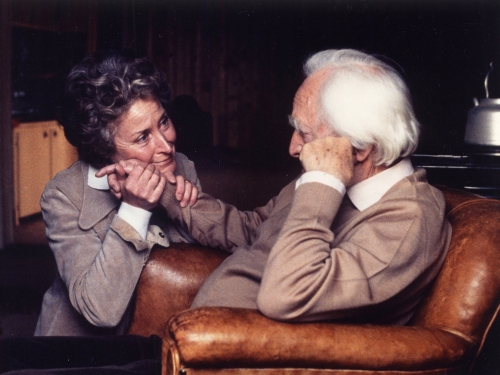

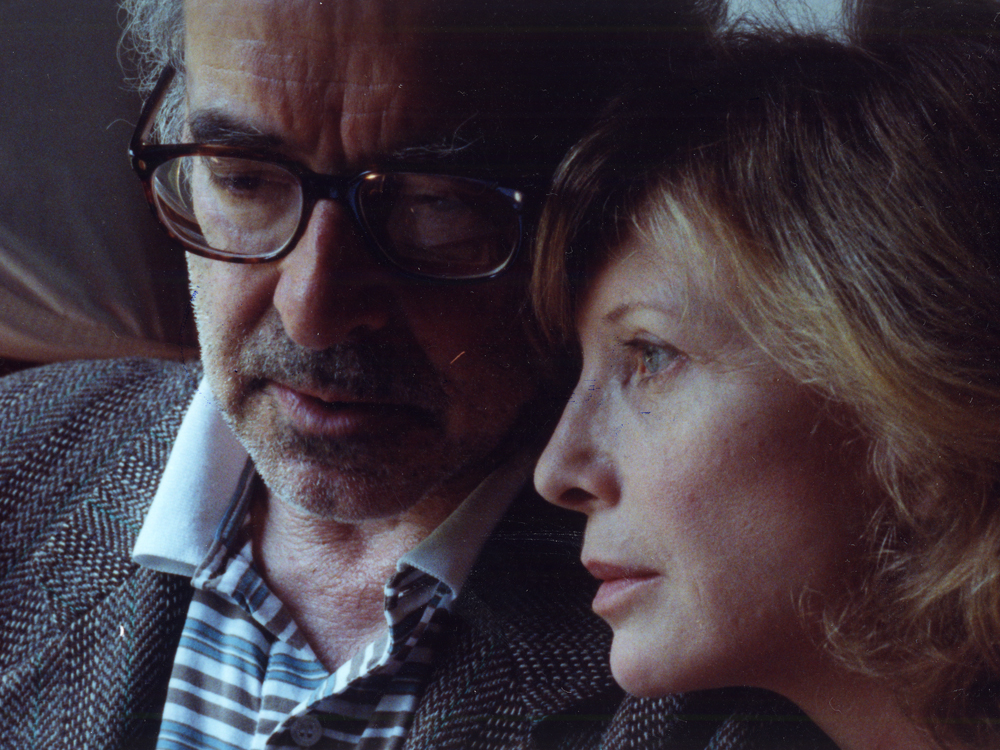

How to give shape to commonality in difference? In Nous sommes tous encore ici (1996), originally devised for theatre, this question is approached using extracts from the work of Plato and Hannah Arendt that resonate in the life of a couple played by Jean-Luc Godard and Aurore Clément, who unmistakably evokes the presence of Miéville. In Après la réconciliation (2000), Godard and Miéville themselves act as two of the four characters involved in philosophical reflections on the powers and limits of language and the challenge to learn to live together with someone else who will always remain a stranger. Sometimes brutal and confrontational, then tender and comforting, Anne-Marie Miéville’s work continues to trust in “the love we are struggling and toiling to prepare the way for, the love that consists in two solitudes protecting, defining and welcoming one another”. (Rilke)

Stoffel Debuysere (Courtisane) and Gerard-Jan Claes (Sabzian)1

- 1This Collection is indebted to the publication ‘Pas de deux. The Cinema of Anne-Marie Miéville’, compiled and edited by Sabzian, Courtisane and CINEMATEK.