One Spectator Among Others: Rebecca Jane Arthur

In the series ‘One Spectator Among Others’ Herman Asselberghs and Gerard-Jan Claes invite various passionate film lovers to elaborate on their viewing practice by email. Filmmakers, artists, critics, researchers, authors, programmers, cinemagoers, TV enthusiasts, Netflixers, YouTubers, torrent users... Which customs and habits, regulations and prohibitions, places and patterns are part of their viewing practice? What place does film-watching have in their professional and personal lives? And is the movie theatre (still) part of their relationship with film? The series offers an introspective view of spectatorship as an activity and attitude, as a tenacious practice of watching, listening, reading, feeling, doing and thinking, with the spectator as a writer of their own singular story, with their own personal style, vocabulary, and idiosyncratic use of accents and punctuation. But always also merely one spectator among others.

Professional spectators and Sunday viewers, economical viewers and polyviewers, always-and-everywhere-viewers, legal and illegal viewers, model viewers, social viewers, solitary viewers, solidary viewers, distracted viewers, enchanted viewers, youthful viewers, adult viewers, secret viewers, onlookers, eccentric viewers, gloomy viewers and peepers. Never before have there been so many opportunities to shape one’s own viewing practice. Never before have people watched so much, at all imaginable times and places, in all conceivable positions and relations. Our film-watching has been atomized. We look in a fragmented but not necessarily aimless way. We may watch the same films but not necessarily at the same time. The film spectator has taken to the street. Waiting for the metro, someone bursts out laughing at who knows what on their smartphone. Down the street, someone is sitting on a bench, moved by the emotional denouement of an old romcom, or excited at the trailer of the next superhero movie. Our social life is punctuated by (pressing) questions, (cautious) recommendations and (resolute) judgments about the films available: “Did you watch this? And have you seen that? Not to be missed! Make sure to check it out! Overrated!” With all of the viewing pleasure, but also the overchoice, overkill or forbearance that entails. ‘One spectator among others’ attempts to see the trees for the wood through a simple observation: we watch. Then, questions arise. How, what, where, and why?

After the first instalment with Herman Asselberghs, we continue the series with Rebecca Jane Arthur, a Scottish visual artist, living in Brussels. She is co-founder of elephy, a production and distribution platform for film and media art based in Brussels, and project coordinator of the Creative Europe-funded project On & For Production and Distribution (2018-2021), conceived to support the field of artists’ moving image. Arthur’s writing on moving image has recently been published by Sabzian and Film Place Collective. Her most recent publication, BE GOOD, IF YOU CAN’T BE GOOD, BE GOOD AT IT Boom Boom Boom Boom (2021), brings together her correspondence with fellow artist Eva Giolo on the act of writing and of filmmaking.

This conversation took place during the first and second lockdown in 2020.

Herman Asselberghs and Gerard-Jan Claes: Why don’t we start at the very beginning? We are curious to know what happened as soon as you decided to accept our e-invitation to participate in this series?

Rebecca Jane Arthur: Ever since you proposed to do this remote, pen-pal-like conversation with me, I have been journeying back in time into my viewing memories. They’ve even come to me in dreams over the past while – you know, the lucid ones that are filled with thoughts that spill from your waking hours into your sleep; ones that you can almost control, zap on or off, pause or rewind if you’re awoken. In almost illegible, excited scribbles on the nearest scrap of paper, I started to jot down some of the moving image memories that presented themselves, lest they be forgotten.

My memory-triggers graffitied the back of a ripped-open envelope: cinema magic – Beauty and the Beast (Disney 1991); my downstairs neighbour’s extensive cartoon video collection; my upstairs neighbour’s equally exuberant horror film collection; the hand-me-down black and white TV that made me feel 8 going on 18; the independent video rental turned Blockbusters; the escapades of Jessica Fletcher as primetime Friday night viewing (accompanied by a special treat from the ice cream van, a Mars, Snickers, Bounty or Twix); detective afternoons with Gran and her suitors: Morse, Frost, or Monsieur Poirot; news (hours upon hours!) with Dad and the televised tragedies of the 90s (Rwandan Genocide, Yugoslav Wars…); Absolutely Fabulous (BBC 1992, 1994, 1995) with Mum and how I’d recount it verbatim to her oh so patient friends; the birth of the DVD player… The sparks were flying as if from a fused TV cable!

You are describing viewing memories here that obviously correspond to a very different time in terms of the possibilities of viewing – video collections, a black and white TV, video rentals and “the birth of the DVD player”. If you compare those viewing memories to your current viewing practice, to what extent do you create viewing milestones today? To what extent has this viewing practice changed?

Immediately, I’d say that today’s difference is found in the physicality – or more precisely, the lack thereof – of the whole (viewing) experience. Now, it’s safe to say that I’m generally more autonomous from physical objects and beings – from a television set to start with, from a family unit for another. Born in the mid-eighties, my earliest viewing memories stem from television programmes – when I wasn’t yet in control of the remote. The nineties allowed for degrees of independence in my viewing practice, which were determined by what I could get a hold of – literally! You know, video tapes or, later, DVDs. And my family weren’t the kind to buy into accumulating collections of any genres… They were hell-bent on me reading books instead of being in front of the box, which backfired with me rather spending time at my neighbours’ homes. Then, of course, films were things, not weightless digital files. Streaming was non-existent. Until the late-80s in the UK, I recall that even the seemingly endless flow of television did, in fact, come to a close. Nightly, at the end of the watershed, there’d be a place holder on screen until moving images were awoken again the next day with a morning talk show or children’s cartoon (depending on who’d seize hold of the remote control first that day). Of course, nowadays, our streams of unconsciousness can be endless, timeless, boundless…

Accessibility and knowledge are key to the differences I experience now. Now, one can “acquire” almost anything on the Internet, and for free. You just have to know what you are looking for, and someone somewhere will even help you find it. I’m thinking of the walled communities where you can participate in the underground dealings of film. Once on the inside of these safe zones, you can ask your gated community for their help in finding your heart’s desire. Perhaps what didn’t change so much, though, is that we still want to “pass things on” to one another. And find joy in doing so, sharing the things we celebrate, even if hands never meet. In terms of viewing recommendations and tips, now they are just transported quicker – and even via strangers living at other sides of the globe. There’s no longer the need to run up or down the stairs to the neighbours!

In regards to creating milestones, well, I’d say that I’ll have to wait and see. This digital turn that we are experiencing now could be named a milestone.

Let’s take a closer look at your recent intake of moving images.

Recently, as with most, my viewing is confined to my own domestic setting. The upside of which is, in fact, that more portals have opened up than before, so I’ve been experiencing things far from my physical reach. The other evening, for instance, I welcomed Laurie Anderson into my home for a magical bedtime story – Lecture 1: The River | Laurie Anderson: Spending the War Without You (Norton Lectures, Harvard) – streaming live from the US. Then, some days later, I met her again in Paris, at Rencontres Internationales, when she had a “rencontre” of her own with an old friend, Sophie Calle. They invited us – hitchhikers – to travel with them in reflection on their practices, friendship, and happenings in their lives. Whilst the world was “tuned in”, however, the conversation was, somewhat, awkwardly out of sync. Not (visibly) physically, in terms of lips moving out of time. Rather, I’m speaking in terms of thoughts travelling the airwaves and getting lost along the way, always arriving too late to catch up. These two travel companions were operating from different time zones, and the slight out-of-time-ness in their conversation led to lofty cringe-worthy moments of malleable misunderstandings. Afterwards, they appropriately screened Calle’s film No Sex Last Night (1996), a documented road trip through the US about two members of the opposite sex (starring Calle, herself, and a guy she’d once “met in a bar”, Greg Shephard) who were themselves out of step with one another – hence the title.

Normally, an average Belgian audiovisual weekend of mine would be solely bicycle driven and it would combine the visitation to off spaces, galleries, institutions, concert venues and a flutter online – perhaps on a lazy Saturday morning or a subdued Sunday evening. With the new realities of a semi-constricted lifestyle, I tried to log my (moving image) movements one weekend this winter – from an extensive cycle from the European quarter of Brussels crossing into Flanders in order to visit Anouk De Clercq’s solo show Here it Comes, the Future at CC Strombeek on a Friday eve to flying down the hill into the belly of Brussels on a Saturday afternoon to meet Tony Cokes’s solo If UR Reading This It’s 2 Late, Vol. 3 at ARGOS. Afterwards, at home, curtailed by the curse of curfew, my flights of fancy on the Net were somewhat trickier to track. Many flight paths were simply governed by chance; looping and spiralling from one thing to the next.

Setting off from my “real-life” experience at ARGOS, I landed at a BAK-talk online called Tony Cokes: To Live as Equals, a talk with Cokes and Irit Rogoff (listening whilst cleaning up). Then, following the advice of Cokes, I set off from Utrecht to London for Kodwo Eshun: Mark Fisher Memorial Lecture at Goldsmiths on YouTube (listening while cooking). Going down the YouTube rabbit hole led me to watching an excerpt from Love is the Message, the Message is Death (2016) by Arthur Jafa (watching whilst eating – although it felt inappropriate). After that, and a glass of wine, I relaxed into the impossibilities of consciously mapping a night on the Net. (I mean, why bother when you can grab a screenshot of your viewing histories when called upon, right?) From there, it was a downward descent onto Netflix – I think. I’d had my full of thoughts for the day.

That sounds like a full programme. Still, it doesn’t feel busy or hurried because a substantial portion of it seems to be so much part of your daily routines in domestic spaces.

The vulgarity of my distracted viewing – cooking, cleaning, eating whilst absorbing, consuming, chewing – is to be blamed on the fact that my audio-visual nourishment often occurs in the hub of my home, the kitchen. My primary source of news and entertainment, the radio, is in the kitchen. However, when I know what I’m hungry for, I’ll put on a specific (web-found) programme or I’ll “switch on” YouTube, which tends to take my laptop on a dance around the kitchen tops, always being moved so I can hear it best, above running or boiling water, above the whirr of an extractor fan, or into my line of vision if it’s a programme that demands my eyes as well as my ears. For the most part, though, I’m happy to glance behind me once in a while to “see” what’s going on.

Your kitchen has the allure of an information hub. There’s, quite literally, cooking with images going on?

Did you know that the noun “kitchen” has a secondary definition? Apart from a space to prepare food, and listen to YouTube, it is the name given to the percussion section of an orchestra. I like this thought; it’s noisy, tinny, rhythmic, hot, lively… Far removed from the sedate, darkened space of the cinema! And when I’m not in company, I like to shut down my thought-train and soak up some words, someone else’s thoughts, ideas, some distraction. Thus, most of my YouTube experience is an aural one. I treat it like the radio, as an audio archive or podcast provider, for interviews and lectures and such, and continue my business, with people, like music, in my ears.

In my house, “I read it on YouTube” is a commonplace punchline! This “joke” began when I was studying art, combining an exploration of theory and practice with working to make the rent, and running from one gathering to the next. On matters that were pressing to my student-existence, I needed information, confirmation, elucidation, and quick. Adding a voice and/or image to one or another theory helped it land. Now, though, it’s just a tool that’s between learning and entertainment. Yet, still, I’m often making a reference to a programme, an interview, that I’ve discovered online in its archives. Hence, at home, there’s some joking about the legitimacy of my sources.

Needless to say, you’re definitely well versed in the use of YouTube. However, you don’t belong to the generation that grew up with the obviousness of the Internet.

Indeed, Internet wasn’t in my reach growing up. It only came into people’s houses after broadband was established in the UK, after 2000. Then, over a decade, it became commonplace – steadily, gradually, without me noticing it. In any case, my family weren’t what you’d call early adopters. By the time my mum installed it at home, I was already long gone, living abroad, with my back turned to the advances of the world-wide web.

Recently, maybe you’ll laugh at this, but I was reminded of that generational divide when I joined the Belgian-VOD platform Avila and rented Because We Are Visual (2010) by yourself (Gerard-Jan Claes) and Olivia Rochette. I met this film on a special occasion during lockdown back in May, on my partner’s (Jordi’s) birthday. Having missed the rise of the whole vlogging phenomena, I was very moved by it, by these teenagers sharing their intimacies online. And what an apt “lockdown” movie! Some characters – all of them young vloggers – seem helplessly alone, in front of his or her screen, desperate to connect with the outside world, whilst talking into the void, into the silence. Other personalities seem to be (prematurely, clairvoyantly) practicing their influence among the masses, or whoever actually knew then about YouTube and tuned in. Showcasing the power of practicing one’s prerogative and the vulnerability of revealing one’s pain, with humour and sadness, the film provided thought for a commentary on society of not only some ten years ago but also of the now – with digital systems heightening in importance as contagion free connectors and with all of the reports of the social affects confinement was, and is still, having on people’s psyches, especially young people. We did find, however, that the charm of then was due to the naivety of the mode of expression. Although the technical aspects that made video creation and distribution so democratic and widespread at that time were revolutionary, now they would be seen as primitive. As Jordi pointed out, nowadays, serious vloggers or influencers would have rigged up their cameras inventively, applied titles, tunes, and special effects to their channels, and edited their videos to show the best side of themselves before uploading them onto the world’s stage. In the scene with birds flying and skateboarders skating, we were made to recall the simplicity and innocence of then – a time far removed from the self-conscious, calculated media self-representations of the now.

How does your embrace of a sprawling YouTube-methodology relate to, let’s say, a visit to CINEMATEK? Do you feel like you need to switch from one mindset to another? Do you need to adjust upon entering the cinema or during that transitional phase when the lights dim?

Okay. Cinema. I’m not exactly loyal to screens or venues. I’m watching, listening, soaking up sensations without a great deal of sentimentality towards the conditions that the image or sound is delivered in. Which isn’t to declare a lack of appreciation for the perfectly balanced realms of the cinema. It’s rather to not demarcate the lines between experiences of content, which I can appreciate flowing through the airwaves, or coaxial cables, just as on the silver screen. And often, these experiences are intertwined. One leads to another. Thus, to the notion of mindset, and having to readjust, I’d say that my consumption, my intake, is fluid. The only mindset that I have to calibrate before entering a darkened room is my internal clock. Time is everything. I can enjoy slow cinema if I have some warning. And I want to be ready to bite from the get go if a film is styled like a flash fiction. But there’s nothing worse, in my opinion, in not knowing how long something will last. That’s the moment when I alter my mindset, when the duration is set.

Entering the cinema, I buy myself time. Time for attentive viewing, unlike the fragmented domestic absorption of thought and distraction to images that I practice daily. No, the cinema is about the holistic experience, both sight and sound, and the pleasure derived from that artform. It’s serious business therefore! And it’s business that I tend to attend to alone: for work and for pleasure too.

In pre-Corona times, did you go to the cinema often? Was your frequency in cinema visits related to your mood, to your being in or out of a relationship, to your budget, to the time of day, to the weather or the seasons?

I’d say I have sporadic cinema patterns, defined by periods of life. As a youngster, the movie going experience was a special outing with neighbours or family members and each time was a kind of indescribable magic – especially sonically, with that all-encompassing 5.1 surround sound that enticed you inside of the enchanted castle, lured you into the green depths of the jungle, plunged you into the darkest watery fathoms, or took you soaring off into space. When old enough, it became a regular Saturday afternoon date with my school friends. In those days, I went to the cinema for every blockbuster going (Sister Act, The Addams Family, Edward Scissorhands, Wayne’s World, Romeo + Juliet – 90s stuff). The only kind of cinema on offer in our town. Growing up in a small historical town in Scotland, Dunfermline, there was but one cinema, Robin’s Cinema, at the top of the High Street. That cinema closed when I was 16 or so. It died a sudden death when the multiplex, the Odeon, opened at the fringe of town. You’d need a car or some kind of wheels to reach it, so I went less often from then on. In any case, at that age, I was frequenting our capital city, Edinburgh, more often by then. Within 30 minutes, you could hop over the water by train and be flooded by choice.

Then there’s the cinema of my wander years. No matter where you go in the world, you can pop into a cinema for a familiar experience. One that would be the same (apart from the subtitles) from San Telmo to San Francisco, from Mexico City to Mechelen. The film, that is, not quite the venue. There’s, of course, a generic cinema interior: a theatre with red seats attached to sloping floors. But my most memorable cinema experiences were in some pretty unique places: the kind of places that are full of people with less conventional stories, showing the kind of cinema that’d be hard to find in the mainstream. I lived in Amsterdam on and off for a number of years, and there alone I met a fantastic array of makeshift cinemas: on hippie-run boats, in no man’s land warehouses, in old churches, and in squats of all shapes and sizes… Although there were, of course, a variety of fully-fledged cinemas too, you could meet independent and auteur cinema at a steal in the smallest of venues, such as Filmhuis Cavia, a 40-seat non-profit venue in the neighbourhood of Wester Park (Westerparkbuurt) above a kickboxing gym, or in the most independent of spaces, such as the screening evening Cinemanita that’s found literally underground, in the basement of a bar/club/artists’ space called De Nieuwe Anita every Monday night, and is run by the legendary Jeff Babcock—an American ex-pat cinephile who’s made a life out of programming films in all of Amsterdam’s off spaces. In these spots, you could always trust in the programming, but those weren’t the sort of places that you’d be guided to by the weather. You couldn’t just pop up and expect them to be open.

It is interesting to notice how you emphasize the social, family and communal aspect of the cinema experience over an interest in the history and aesthetics of film per se. Would you say that the audience as a concrete community, whether it is your family or a “scene”, plays a more important than or at least equally important role as the work shown?

Of course, I have to think now of Anouk De Clercq’s study of screening venues: her book Where is Cinema? (Archive Books, 2021). It’s a series of conversations with cinemas of her choosing. This could have turned into a non-exhaustive list of initiatives, a life’s work, but she made a selection based on her personal cinema-going experiences, priorities, and discoveries in order to showcase the different faces of cinema. Yet, no matter how diverse the screening venues may be, from Bogota to Berlin, their core is the same: to experience cinema together. And what comes across from all of the portraits of initiatives is how the “scene”, as you put it, is intrinsically important to the cinema-going experience. Without others, it collapses, or becomes marginalised or even non-existent. Which is generally the sad fact for smaller towns, like where I come from: they either can’t muster the audiences or can’t afford the screening fees, let alone the equipment and premises.

How do you end up in the cinema today and why? For entertainment, on the recommendation of people, or do you follow the work of certain makers?

My cinema behaviour of late is defined by periodic immersion in film at festivals (recent years include Courtisane Festival, CPH:DOX, FIDMarseille, IFFR, Kaunas International Film Festival, Oberhausen), premieres of local filmmakers’ films in Belgium, featured cinema programmes at art venues, cultivating a knowledge of cult or classic cinema through film museums, and cinema tourism when visiting a new city or living in a new country temporarily.

The aforementioned scene starts close to home, of course, with the works of local filmmakers. Thus, the filmmakers I follow are, first and foremost, my peers (who are often friends too): from elephy, Dagvorm Cinema, Monokino, Messidor, Sabzian, Avila, De Imagerie, WET Film, to name but a few, and many other individuals also. Further, I follow works from fellow artist-run production platforms like Auguste Orts, Balthasar, Escautville, Jubilee. For recommendations, I listen to my surroundings, keep my eye on certain screening venues, on specific festival selections, and online film agendas or columns.

It seems that your preference for watching films at film festivals is the flipside of surfing YouTube in your kitchen at home, right?

Indeed! But similarly to my first experiences with YouTube, which I used like a library during my studies, it’s again a work–life relationship that I have with festivals. The experience of film festivals may be as entertaining as can be, but for someone making films, thinking about films, writing about films, well, it’s still work. So, to me, it’s acceptable that the conditions of film festivals are demanding. I’m there to be challenged, to learn and hopefully to be stimulated too. I’m always excited to put a stripe in my diary through the days that will be given up, one hundred percent, to a festival of my choosing and go in there and see as much as I can bear. Equipped with a typically overzealous itinerary, I’ve learned to prepare for all of the physiological challenges that’ll be thrown at me by packing my newly gained, freshly printed, corresponding tote bag full of survival strategies in order to make sure that I don’t have to miss a blink. Then, I’m prepped for battle, my body against the sedentary time-based art experiences that the likes of Lav Diaz or Wang Bing could throw at me. Psychologically, I can also be challenged at festivals, gripped by the frustration of FOMO when faced with overlapping programmes. Perhaps the worst adverse reaction is oversaturation: overdosing and becoming numb.

My favourite festivals are somewhat reminiscent of my kitchen, in terms of cosiness. They are personal, warm, well-stocked, and unpretentious, not hanging off of premiere statuses and competitions. The most hellish experiences I’ve had in cinemas were at competition programmes! Whereas some of the best experiences I’ve had were at “artist-in-focus” programmes, where you sit down, take time, and really get to know someone’s work. You become familiar with their journey, life, and politics, and get a glimpse of the works that have shaped them – earlier, perhaps less celebrated works of their own or works of their choosing by others. What a treat! At Courtisane Festival, Ghent, over the years, I’ve been fortunate to experience that with the likes of Annik Leroy, Michel Khleifi, and Alia Syed, for instance. That festival, in particular, offers carefully curated experiences and the size of occurrence that allows you to come in close proximity with the makers, and perhaps even break bread together!

It’s fair to say that Courtisane Festival is the real highlight of my cinematic calendar. And I’ve met more women who make movies there (at least, I’ve met their films) than any other cinema space I’ve encountered: Anouk De Clercq, Ana Vaz, Beatrice Gibson, Chantal Akerman, Chloë Delanghe, Christina Stuhlberger, Deborah Stratman, Els Opsomer, Eva Giolo, Fairuz Ghammam, Jayne Parker, Jeanette Muñoz, Joyce Wieland, Laida Lerxundi, Laure Provost, Lis Rhodes, Lizzie Borden, Manon de Boer, Mary Jiménez, Narcisca Hirsch, Stephanie Beroes, Ute Aurand, Vivienne Dick, Vanalyne Green… So many influences, influencers.

The work and makers you mention mark out a clear field. On the one hand, there is a clear preference for work that straddles the worlds of visual art and cinema; on the other, there is also a preference for female filmmakers who have built their own cinematic space in a very singular way. What is it about this work that appeals to you so much?

This is a bit of a bombshell question to ask. I mean, it’s huge! I could write pages on these subjects alone. For lack of space here, though, I can’t unpack each filmmaker’s practice. But I also can’t homogenize their practices by typing one easy answer. I’ll do my best to propose a very subjective reading of these “kinds of works” and why the aforementioned makers appeal to me.

First off, I’ll pin down where the attraction towards such filmmakers began. The most direct answer to that is art college. I had the privilege to study under the guidance of many women artists who I admire (Aglaia Konrad, Anne Daems, Dorit Margreiter, Sasha Pirker, Marion Porten, and Anouk De Clercq), and a couple of men too (for one, Courtisane’s director, Pieter-Paul Mortier, was a great film-influencer to be around). These artists undoubtedly shaped me and showed me the kinds of films that hadn’t yet been readily available to me: moving image that was often derived from visual arts. I’m indebted to them for that.

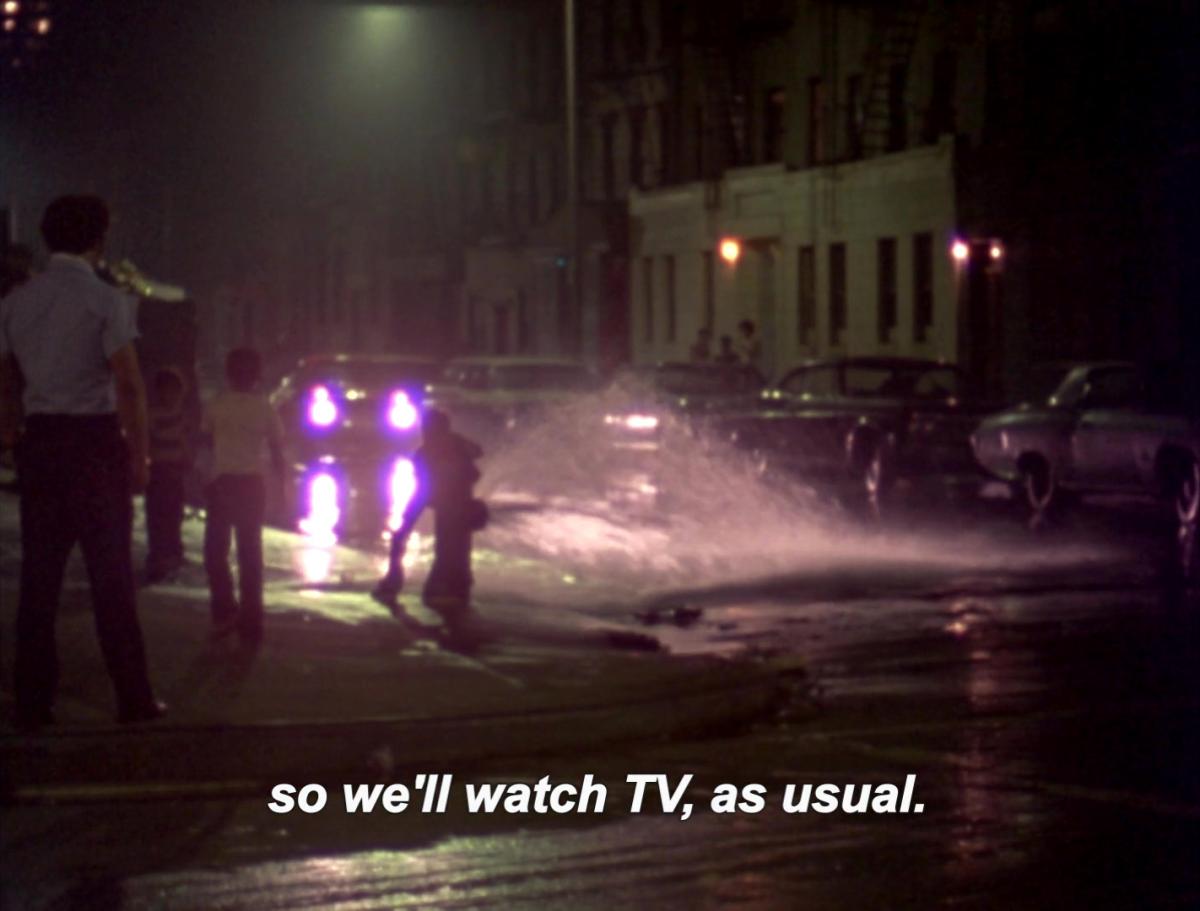

In terms of whose work I’m drawn to, there’s a certain sensibility in the filmmakers I’m drawn to which is perhaps more political than it is aesthetic. In the “look” or “feel” of a film, I’m drawn to those who find their own rhythms, that stir me and cause a little chaos or that offer a little comfort. Sometimes, I can find solace in the most brutal of stories being told, precisely because someone was so bold and courageous to make them. I’m thinking of Tracey Emin’s Why I Never Became a Dancer (1995) or Jarman’s Blue (1993). Works that bruise you a little and stay with you forever. I can find refuge also in silent spaces, non-narrated spaces, in journeys paved by imagery or sound — I’m thinking of Aglaia Konrad’s Il Cretto (2018), or Els Opsomer’s 10th of November (2008), or Ute Aurand’s Hanging Upside Down in the Branches (2009). And there’s great pleasure to be found in structured yet poetic works that play with storytelling itself; the kind that can sweep me away in their words or images, and then I’m left decoding them, processing them, later, on a re-run: Deborah Stratman’s Illinois Parables, Alex Reynolds’s This Door, This Window, or Chantal Akerman’s News from Home (1974) – my absolute favourite film of hers. And I’m completely impressed by and in awe of feature fictions by Lucrecia Martel, Nina Menkes, Kelly Reichardt… They make me want to dream big. But I also have the legacy of Margaret Tait to look back on, in order to remind me that size doesn’t matter.

Curfew, lockdown and quarantine have halted the festival experience for now and imposed a different regime of watching films and such. We’re developing new habits of attending to screens. We’re watching at different hours, in different stretches, possibly even different things.

Whilst generally cocooning because of the pandemic, my days are marked by hours worked and ushered along by physiological needs. Thus, in order to meet open spaces, I’ve been delving into moving images in varying forms. My film choices have been made at two ends of the spectrum: short films or cinema that’s over 3 hours long (such as Robert Kramer’s monumental Milestones or Luis López Carrasco’s The Year of the Discovery). Actually, I must admit that I’ve been breaking down the “long-reads” into shorts or mid-length films by watching them in partitions over consecutive evenings. Something that wouldn’t be possible in a cinema. Generally, I’ve been finding sustenance in succulent fragments of ideas, of confessions, of realities.

Once again, the link to YouTube appears: you cut long films into small clips and fragments that are in sync with your daily life.

Fragmentation is, indeed, my form of comfort right now. It’s also echoed in my reading of late, skipping between Moyra Davey’s Index Cards, Bernadette Mayer’s The Desires of Mothers to Please Others in Letters, and CAConrad’s A Beautiful Marsupial Afternoon – New (Soma)tics. From notes on writing or anecdotes on the creative process, to poetic prose on daily life and poems that reach to the cosmos, each offer short and undiluted hits. Words, as weapons of survival, to carry along with me in my day.

Are there any other new viewing habits that have developed during this period?

Well, there’s the notion of live – online – screening time that I found novel during the first wave. Have you participated in any of those talks or events? Via Facebook, I attended a number of LUX’s online talks on moving image practices. I watched representatives from WANDA collective speak at Gent Film Festival. I attended a Rave organized by Dagvorm Cinema. And I had a number of the Tuesday Talks of Kunstenpunt/Flanders Arts Institute in my kitchen, dining with me. The funny thing with these experiences is that you have this phenomenon of “watching together” à la cinema! Sometimes, you’ll see people you know join the online screening, see them react, with love hearts, smiley faces, thumbs up or down, flying over your screen, and you can type a message to anyone as you watch. Okay, it’s not that I use all of these features. But it is to say, as cynical as I really want to be about the platform, I still get my kicks there, from time to time, due to the content that’s shared.

A new viewing platform that I’m very excited about, on the other hand, is Another Screen, from the creators of the feminist film journal Another Gaze. Now, that’s a programme to watch!

And where is Jordi when you are virtually spending time elsewhere? For dedicated spectatorship surely abides company, provided there’s room for negotiation. In other words: who is holding the remote control at your place?

Oh, Jordi’s never too far off! Only, he’ll have his own headphones on and be listening to music or a podcast. When we are watching something together, I tend to keep control of the remote. But that’s to do with the volume. For me, the volume can always go up a notch. I want to feel inside of the soundscape. And I’m very frustrated by not hearing things properly, so I often choose to watch things with captions also. In any case, I can’t change the channel with the remote, as we don’t have a TV package. When it comes to finding material online and being in charge of the “mouse pad”, well, I’ll admit that I’m a bit domineering there. But I’m just quicker at it than he is!

And how are the negotiations conducted on what will be viewed?

I’d say we both often have different viewing priorities. For me, it’s often business. I’m still working, researching, networking – my attention “besieged”, as Franco “Bifo” Berardi would put it. Jordi’s business is music. For him, viewing-time is pure relaxation and entertainment. He has no plans to rival it or write about it, unless it contains jazz. Besides football, and talking about football, he generally goes with my flow for a shared-viewing experience. Recently, he joined me for (part of) The Year of Discovery online at Berwick (which I broke down into three viewing sessions), and Stephanie Beroes’s Recital and Valley Fever, both via LUX online, and Milestones (part 1 and part 4, according to my own partitions). But when I made an evening of as many Laida Lertxundi films as I could get my hands on, he sat that one out for his own screen time at an online concert. No negotiations necessary. We do enjoy time spent alone when no compromises whatsoever must be made!

When I’m away or busy, he’s watching Extra Time or Brooklyn Nine-Nine or BoJack Horseman. When he’s looking the other way, I’d watch something I know he wouldn’t miss too. I’d watch-listen to Anne Carson giving a lecture, or an artists’ film that’s on my watch list, or some British period drama, or something absolutely frightful that he’d absolutely hate, like any American hospital drama. Now, that would clear the room for sure! Those kinds of works bring me to an emotional space that Jordi doesn’t feel the need to share. Tearjerkers, such as life or death stuff as ER or Grey’s Anatomy are, bring me in touch with my emotions, ones that I don’t often let show. Quite the contrary in emotional stature, Jordi doesn’t need much to show his feelings! His emotions are easily triggered by words that affect him, which feels like at the drop of a hat to my somewhat frostier-British sensibilities. I, on the other hand, need the whole shebang to get me going: the sappy story, the music, the full throttle life or death tropes – the all or nothing kind of thing. I know I’m being played, but that’s what I’ve subscribed to by pressing play: to feel something other than what I feel from the horrors I hear on the radio each day that make me feel powerless and without the right to cry. The artworks and lecturers, however, are things that we can share. But Jordi can’t always muster the same enthusiasm for my picks: which I absolutely demand. If I’m presenting something to him that I think is not worth living without and he shrugs it off – well, that can lead to existential questions about our relationship! Of course, I exaggerate. But it’s not worth it. Anyway, he has his own people of interest to listen to.

When he leads the way, he brings me to places off my beaten track, like streaming-evenings of Brussels Jazz Festival at Flagey or afternoons at the World Championship Cyclocross (WK Veldrijden). And when life is at its best, when I can relax and switch off, we watch films or series on VRT.NU, MUBI, DAFilms, Netflix, or on DVD. We enjoy your middle of the road detective series, crime series (not too gory, though). Things like The Wire, Top Boy, Spiral, Undercover, How to Get Away with Murder, The Bridge, The Fall… We also enjoy popular contemporary dramas: Little Fires Everywhere, Big Little Lies, The Good Wife, The Good Fight, De Twaalf, NARCOS… Or documentary series or films, like The Last Dance, Pretend It’s a City, Hillary, Becoming… Both of us can sink into these kinds of things. They aren’t demanding in terms of duration span, roughly between 40 minutes to an hour long. Meaning, after one, you can feel satisfied with your visit into another realm. Two episodes, back-to-back, is always a tempting prospect, and heartily satisfying to indulge in! But then we’re probably wilting – or buzzing so much that we can’t sleep afterwards. I could binge on, ignoring my eyes burning, but he’s quite restrained. Which makes him a healthy viewing partner. Most of this stuff is found on Netflix or the likes, so it’s all pretty homogenous in terms of production values: all glossy, shiny, sleek, and often action packed. Full of drama and thrills. One rather disputed watching technique to counter this spike in adrenaline is my urge to check the timeline in moments of suspense. By calculation, I can tell who is guilty or how a drama will end by checking where we are – in time – in the film or episode. He hates this! So, I try to resist it in his company.

In the wide range of what’s available through various channels and on different platforms – and that you clearly make good use of – is there anything that you avoid or refuse to watch?

Generally, what I try to avoid is reality TV: Big Brother, Strictly Come Dancing, The Great British Bake Off, The Antiques Road Show – all of that. I find those programmes hard to suffer. Which means I’ll probably never learn to waltz or bake fancy cakes or whatever. And I’m okay with that. Perhaps, what’s missing in this refusal, in a larger sense, is a connection with “folks”, as Obama would say. But, again, not having TV makes a difference here. I don’t stumble upon these things. They aren’t background noise. I’d have to look for them, and my aim is to escape them altogether. I also can’t be bothered with things that you’re supposed to watch on a more than once weekly basis. Soap operas, for example, aren’t relevant to me now, at this stage of my life. As a kid, I watched Australian soaps like Neighbours or Home & Away, in which nothing much really happens. It takes watching half an hour a day spread out over years for the girl/boy next door romance to take any form, let alone a kiss. So you become exacerbated, and give up. Juicier soaps as Eastenders were never allowed, as a child. Which made that one in particular more appealing, and I’d sneak a few episodes into my routines from time to time. But it never became a habit and the intrigue tapered out, quite quickly too. I don’t know what you have here in Belgium that’s comparable to soap operas like Eastenders or Coronation Street? I’d be able to sit through one or two, out of curiosity, before I’d want to regain my autonomy from the box.

Thus, you want to keep a certain autonomy, no fixed appointments?

I want to keep my freedom, yes. And my time! It doesn’t suit my current occupations to be busy keeping fixed appointments with programmes that I find so utterly unattractive.

So also, as a professional viewer, for example, are you not interested in those popular forms? What is there in watching these programmes that you find repulsive?

It’s not that I find them repulsive. Of course, in reality TV, it depends on how people are depicted: if they seem exploited or if they appear to be in control. However, generally, it’s rather that I’m just not interested in watching people try to win competitions. I understand that there’s a fascination in seeing your regular Joe or underdog achieve their dreams: to be the nation’s next voice, master chef, or to win a car or a family holiday. It’s just not where I seek inspiration or entertainment. I have friends who make artworks about popular culture, and it’s fun to hear them buzz on who’ll be the next drag queen or what Britney did on Tik Tok, etc. But I’m happy to live these moments vicariously and enjoy their enthusiasm.

I have to say, though, it’s far more interesting to see these kinds of shows – soap operas and reality shows – in a foreign country. I mean, there’s far more for me to learn, to observe, to find novel in ways of expression from the veneers to the vernaculars. I don’t need to go online, or turn on the television, to meet aspirational British working-class people. That’s the kind of stock I’m from. And sometimes, I’m just looking for escapism.

So we gather you’re not a TV-person?

I just don’t have much time for TV, so I don’t have a TV license. I don’t feel as though I’m missing so much – although my mum is constantly referring to things on BBC iPlayer, which sometimes makes me feel otherwise. But I feel as though I don’t have the time to make the most out of my VOD platform memberships as it is.

When I was younger, I was also select about what I was watching – out of necessity, that is. For most of my life, there was only one TV in our house. So, between school and a massive chunk of primetime viewing cut by the mandatory news marathon – BBC Six O’Clock News, then Reporting Scotland, followed by the hop over to Channel 4 for the 1-hour long Channel 4 News – I didn’t have much time to fill. But as a teenager, given the chance, I was into all kinds of TV dramas: Heartbreak High, My So-Called Life, Party of Five, The Sopranos, Six Feet Under… Which I sometimes had to fight for against more news or satirical programmes! Anyway, I gave up wrestling for the remote when I was around 16 or so because of my very busy social calendar and own societal dramas. And then, I continued to leave that bulky, big black box long behind me, simply because of moving around for years on end.

I didn’t pick up TV-watching again until I was at least 25-years-old, and that was urged by my polyglot Italian flatmate in Amsterdam and my desire to learn Dutch. For educative purposes, he proposed that we watch reality TV! Together, we watched a whole bunch of the “So You Think You Can…” cook or dance or date kind of programmes. In hindsight, I can see that he was onto something there: TV helped me to absorb the language and its tonalities like a sponge. It helped me to familiarise myself with everyday expressions and sent me out onto the streets equipped with the intonations needed to pull off: Ja, hoor (Yeah, sure), Wat zeg je nou? (What are you saying?), Geweldig (Terrific)! So, I got my NT2 (Dutch as a second language) certificate and then quit my life there for Mexico… Which, of course, didn’t strengthen my Dutch language skills, and I had no time for TV there, but I did at least leave the Netherlands having an inclination of society outside of Amsterdam, life in other circles, and with a solid basis of the common expressions in that language.

Did you do the same when you moved to Belgium – use the TV as a learning device?

When moving to Belgium in 2012 for my studies, I had to make an effort to tune into and pick-up Flemish accents, mumbles, softly spoken inside-of-the-mouth quips, quite unlike the outspoken, well-defined, decibels louder Dutch that I was accustomed to. I watched a whole bunch of films like De helaasheid der dingen, Rundskop, The Broken Circle Breakdown… Then series online: Het eiland, Code 37… But I was more exposed to the language by then. All of my theory classes were in Dutch, I had classmates from all over Flanders to broaden my dialectical sensitivities, and Jordi’s relatives from Merksem to test my improvements at each family get-together. So, in Belgium, I didn’t have to get into reality TV. I was living my own reality shock.

By way of conclusion, do you remember the first time you attended a film screening in cinema?

My first time, well… It was Disney’s Beauty and the Beast (1991). My brother and I were invited to the cinema by our downstairs neighbour and her son, the ones with the dream Disney video collection that I mentioned earlier. It was an evening screening, the premiere, and the opening of the repurchased, renamed, renovated local cinema; it was completely sold out. I can’t remember too many more details of the setting than the buzz of a full house and sinking into the dark for it to be illuminated by explosions of light and colour. What unfolded in front of my eyes was just amazing: a singing and dancing candelabra, clock, and closet!

Belle, to me, at that age, was a feminist icon of sorts. She was smart, beautiful, kind, strong, and fearless. In love, she chose literature and brains over brawn. She wasn’t interested in the local stud, Gaston, and the idea of becoming a “little wife”, cooking his meals, mending his socks, and having his babies. She wasn’t waiting to be saved by any man! No way. She was, in fact, the one doing all of the saving (saving her father, saving the so-called beast and, lo and behold, saving her prince). She wanted to find true love and adventure, even if that meant falling for someone who was outwardly unattractive. Somehow, the whole idea of her being held captive by her suitor completely escaped me. The fact that she fell for him is what is called Stockholm Syndrome, right? That’s surely one of the largest criticisms of the film. That, and there’re issues of class, servitude, and I’m sure we could dissect it further.

But “princess culture” was completely of my time. Even before Belle, certainly before I can remember. My mum reminds me that I used to ask her if I was a real princess or just a make-believe princess. Of course, she used to make me believe that I was a real princess, even though I lived in a council flat at the very dodgy end of town. For me, though, my secret princess statute gave me a way of knowing that I deserved much more than my provincial life. And, due to figures like my mum, I knew that you shouldn’t wait around and hope to be saved. You have to go out and seek your fortune. Whatever that may be.

I think all girls – and boys, for that matter – need tales of women protagonists going boldly into the unknown, facing their fears, demons or monsters (although less of the creepy, sexual predator kind), and overcoming challenges with their own powers, their own magic. Only, that magic shouldn’t rely on them winning over a man. I have three young nieces at home (now 2, 4, and 6 years of age) who I like to send stories of women becoming scientists, artists, musicians (a great series of books called Little People, Big Dreams), rather than tales of girls giving up any personal ambitions or careers to live in palaces. Real life examples of empowering women come in all shapes and sizes, all nationalities, all skin tones, all languages, and we must ensure that role models are no longer depicted as muted prototype dolls with the “bluest eyes”.

List of titles

Beauty and the Beast (Gary Trousdale & Kirk Wise, 1991)

Inspector Morse (Colin Dexter, 1987-2000)

A Touch of Frost (R. D. Wingfield, 1992-2010)

Poirot (Clive Exton a.o., 1989–2013)

Absolutely Fabulous (Jennifer Saunders & Dawn French, 1992-2012)

Lecture 1: The River | Laurie Anderson: Spending the War Without You (Norton Lectures, Mahindra Humanities Center, Harvard, 10 February 2021)

No Sex Last Night (Sophie Calle & Greg Shephard, 1996)

One (2019, Anouk De Clercq)

Helga Humming (2020, Anouk De Clercq)

Terrain-Privé (reworked for Studio S) (Gilles Hellemans, 2019)

Evil.11 (The Katrina Debacle) (Tony Cokes, 2010)

The Queen is Dead … Fragment 2 (Tony Cokes, 2019)

Evil.16. (Torture Musik) (Tony Cokes, 2009-2011)

Tony Cokes: To Live as Equals | Conversation Tony Cokes and Irit Rogoff (BAK, 2020)

Kodwo Eshun: Mark Fisher Memorial Lecture (Goldsmiths, University of London, 19 January 2018)

Love is the Message, the Message is Death (Arthur Jafa, 2016)

Because We Are Visual (Olivia Rochette & Gerard-Jan Claes, 2010)

Sister Act (Emile Ardolino, 1992)

The Addams Family (Barry Sonnenfeld, 1991)

Edward Scissorhands (Tim Burton, 1990)

Wayne’s World (Penelope Spheeris, 1992)

Romeo + Juliet (Baz Luhrmann, 1996)

Vers la mer (Annik Leroy, 1999)

In der Dämmerstunde Berlin de l’aube à la nuit (Annik Leroy, 1980)

I Hope I’m Loud When I’m Dead (Beatrice Gibson, 2018)

Saddle Sores (Vanalyne Green, 1999)

Fertile Memory (Michel Khleifi, 1980)

Ma’loul Celebrates Its Destruction (Michel Khleifi, 1984)

Watershed (Alia Syed, 1994)

Unfolding (Alia Syed, 1988)

Swan (Alia Syed, 1986)

Light Reading (Lis Rhodes, 1978)

Fatima’s Letter (Alia Syed, 1992)

Wallpaper (Alia Syed, 2018)

Oumoun (Fairuz Ghammam, 2017)

The Oblique (Jayne Parker, 2018)

Solidarity (Joyce Wieland, 1973)

Wantee (Laure Provost, 2013)

Demien’s Face (Chloë Delanghe, 2014)

Face Deal (Mary Jiménez, 2014)

Come Out (Narcisa Hirsch, 1971)

Guerrillere Talks (Vivienne Dick, 1978)

Shattered (Eva Giolo, 2014)

Why I Never Became a Dancer (Tracey Emin, 1995)

Blue (Derek Jarman, 1993)

Il Cretto (Aglaia Konrad, 2018)

10th of November (Els Opsomer, 2008)

Hanging Upside Down in the Branches (Ute Aurand, 2009)

Illinois Parables (Deborah Stratman, 2016)

Esta puerta, esta ventana [This Door, This Window] (Alex Reynolds, 2017)

News from Home (Chantal Akerman, 1974)

Margaret Tait, selected films 1952 – 1976: Aerial (LUX, 2006)

5 Year Diary (part 1), Magazine Mouth (Anne Charlotte Robertson, 1983)

Wenn du eine Rose siehst/When You See a Rose (Renate Sami, 1995)

Envío for Helga Fanderl (Jeanette Muñoz, 2010)

Leopard (Helga Fanderl, 2012)

Autoficción (Laida Lertxundi, 2020)

Occidente (Ana Vaz, 2014)

Queen of Diamonds (Nina Menkes, 1991)

50 Minutes (Moyra Davey, 2006)

La Mujer Sin Cabeza (Lucrecia Martel, 2008)

Certain Women (Kelly Reichardt, 2016)

Milestones (John Douglas & Robert Kramer, 1976)

El año del descubrimiento [The Year of the Discovery] (Luis López Carrasco, 2020)

Recital (Stephanie Beroes, 1978)

Valley Fever (Stephanie Beroes,1979)

Extra Time (VRT, 2009–)

Brooklyn Nine-Nine (Dan Goor & Michael Schur, 2013–2022)

BoJack Horseman (Raphael Bob-Waksberg, 2014–2020)

ER (Michael Crichton, 1994-2009)

Grey’s Anatomy (Shonda Rhimes, 2005–)

The Wire (David Simon, 2002–2008)

Top Boy (Ronan Bennett, 2011)

Spiral/Engrenages (Alexandra Clert, Guy-Patrick Sainderichin, 2005–2020)

Undercover (De Mensen, 2019–)

How to Get Away with Murder (Peter Nowalk, 2014-2019)

The Bridge (Hans Rosenfeldt, 2011-2018)

The Fall (Allan Cubitt, 2013-2016)

Little Fires Everywhere (Liz Tigelaar, 2020)

Big Little Lies (David E. Kelley, 2017-2019)

The Good Wife (Robert King & Michelle King, 2009-2016)

The Good Fight (Robert King, Michelle King & Phil Alden Robinson, 2017–)

De twaalf (Sanne Nuyens & Bert Van Dael, 2019)

NARCOS (Chris Brancato, Carlo Bernard & Doug Miro, 2015-2017)

The Last Dance (Jason Hehir, 2020)

Pretend It’s a City (Martin Scorsese, 2021)

Hillary (Nanette Burstein, 2020)

Becoming (Nadia Hallgren, 2020)

Neighbours (Reg Watson, 1985–)

Home & Away (Alan Bateman, 1988–)

Eastenders (Julia Smith & Tony Holland, 1985–)

Coronation Street (Tony Warren, 1960–)

BBC Six O’Clock News (BBC News, 1984–)

Reporting Scotland (BBC Scotland, 1968–)

Heartbreak High (Michael Jenkins & Ben Gannon, 1994-1999)

My So-Called Life (Winnie Holzman, 1994-1995)

Party of Five (Christopher Keyser & Amy Lippman, 1994-2000)

The Sopranos (David Chase, 1999-2007)

Six Feet Under (Alan Ball, 2001-2005)

De helaasheid der dingen (Felix Van Groeningen, 2009)

Rundskop (Michaël R. Roskam, 2011)

The Broken Circle Breakdown (Felix van Groeningen, 2011)

Het eiland (Jan Eelen, 2004-2005)

Code 37 (VTM, 2009-2012)

Images (1) and (2) from Absolutely Fabulous (Jennifer Saunders & Dawn French, 1992-2012)

Images (3) and (4) from Because We Are Visual (Olivia Rochette & Gerard-Jan Claes, 2010)

Images (5) and (6) from News from Home (Chantal Akerman, 1977)

Images (7) and (8) No Sex Last Night (Sophie Calle & Greg Shephard, 1996)

Image (9) from Beauty and the Beast (Gary Trousdale & Kirk Wise, 1991)