Gerard-Jan Claes

Gerard-Jan Claes (Belgium, 1987) is a filmmaker, lecturer, author, both founder and artistic director of the cinephile platform Sabzian, and co-founder of the independent film distributor Avila. As a filmmaker, he collaborates with Olivia Rochette (Belgium, 1987). Their shared filmography consists of Because We Are Visual (2010), Rain (2012), Grands travaux (2016), Mitten (2019) and Kind Hearts (2022). Since 2009, the duo provides audiovisual work for choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker and her dance company Rosas. Claes teaches at P.A.R.T.S. and LUCA School of Arts. You can find more information on their films on their website.

Gerard-Jan ClaesGerard-Jan ClaesWeek 42/2025

Film Fest Gent continues this week until Sunday. Don’t miss our selection from the programme, featuring new films by Aleksandre Koberidze, Sergei Loznitsa, Bi Gan, Lucrecia Martel, and Kelly Reichardt.

Yves Boisset (1939–2025), who died last March, was seen by some as France’s most censored filmmaker, and by others as a provocateur who embraced his outsider status. He left behind an impressive body of work of around fifty films, directing major actors such as Michel Bouquet, Jean-Louis Trintignant, and Miou-Miou. His films, deeply rooted in political awareness, tackled issues from the Algerian War to racism, police violence, and media critique. A fan of American genre films and Italian B-movies, he positioned himself outside both the Nouvelle Vague and classicism. Nova pays tribute with a cycle of his early, emblematic films.

On Tuesday, CINEMATEK and the film festival Dames draaien will screen four films by Italian filmmaker Cecilia Mangini (1927–2021). Made between 1960–67, the films showcase her collaborations with Pier Paolo Pasolini, her focus on marginalized youth, and her documentation of southern Italy’s disappearing rituals. Shaped by neorealism, Mangini’s quietly confrontational documentaries blend poetic and political perspectives, addressing social struggles and the lives of Italy’s disenfranchised. Earlier in 2023, Sabzian published a collection of texts on her work: ‘Cecilia Mangini. To Be a Documentary Filmmaker’.

Also at CINEMATEK, the Frans van de Staak retrospective continues this week with two screenings. On Sunday, Windschaduw will be shown. In a text previously published on Sabzian, Johan van der Keuken wrote about the film: “I cannot explain it, but at its strongest moments, Van de Staak is, for me, the filmmaker who comes closest to capturing the very essence of filmmaking.” On Wednesday, Het vertraagde vertrek screens, a close collaboration between Van de Staak and writer Jacq Vogelaar that evolved as a dialogue between filming and writing and grew into a collective process.

Week 20/2025

The Brussels screening collective Cinema Parenthèse pays tribute to the Australian filmmaking duo Arthur and Corinne Cantrill with a three-day film programme. The programme kicks off this Sunday at iMAL with a selection of films from the 1960s and 1970s. On Monday and Tuesday, two additional evenings will follow at Art Cinema OFFoff. Having made over 150 films, the Cantrills are among the most significant figures in experimental cinema. They are known for exploring the Australian landscape and researching the “three-colour separation process.” On Wednesday, Sabzian will publish a primer by Arindam Sen on the duo, offering insight into their trajectory and the (political) stakes of their work. As he writes: “[T]he Cantrills’ absolute commitment to experimental over descriptive forms does not mean that their relationship to the world is closed off. Quite the opposite, they define this relationship on their own terms.”

Also in Brussels, CINEMATEK and Courtisane are organizing a retrospective of the cinema of Billy Woodberry. He was a key figure of the L.A. Rebellion: a collective of Black filmmakers from UCLA who broke with Hollywood depictions of Black life in America. His acclaimed debut Bless Their Little Hearts (1984), co-created with Charles Burnett, stood out for its subtle tone. Woodberry’s powerful, underrecognized cinema resonates far beyond the U.S. and speaks to struggles across the African diaspora. The retrospective starts Thursday featuring Mário, his latest film about Angolan anti-colonial activist Mário de Andrade, with Woodberry in attendance.

On Wednesday, KASKcinema screens Only Yesterday, a Japanese animated film by Studio Ghibli. While Ghibli films are known for blending fantastical elements with deep human insight, Only Yesterday opts for realism. The story follows Taeko, a 27-year-old Tokyo office worker who reflects on her 1960s childhood while visiting the countryside. This contemplative work stands as one of Takahata’s most mature films, offering a reflective and humane exploration of memory, identity, and personal growth.

Week 14/2025

This week’s selection is entirely dedicated to the Courtisane festival, which runs from Wednesday to Sunday in Ghent. From the extensive program, we have chosen three films that each offer a meditation on time and history.

On Thursday, in the context of the release of the publication In the Midst of the End of the World (2024), Sabzian and Courtisane present Ana (1982) by António Reis and Margarida Cordeiro. Set in the Portuguese region of Trás-os-Montes, the story revolves around Ana, a serene matriarch, portrayed by Cordeiro’s mother. The name Ana, a palindrome, reflects the film’s circular structure, symbolizing the cycle of life, further emphasized by the appearance of Ana Cordeiro Reis, the directors’ daughter. Ana blends reality, fiction, ethnography, and poetry, offering a reflection on history, and the individual’s place within it. “‘To play herald to death,’ from Homer’s Ulysses to that of Joyce, has been the sole and utmost purpose of storytelling,” João Bénard da Costa wrote. “Ana is […] a film about the comprehension of this fact.”

Later that day, Courtisane screens Ogawa Productions’ The Magino Village Story — Raising Silkworms (1977). The Japanese documentary collective’s films are defined by their long-term engagement with agricultural communities, intertwining documentary, ethnography, and social history. The film opens with an old woman recounting a folk tale about silkworms, followed by a detailed look at silkworm cultivation. The filmmakers immerse themselves in the villagers’ sense of time, an approach that would later influence Ogawa’s other work, showing, as Markus Nornes notes, that history is not just a past reconstruction, but a living, tangible presence in the present.

On Sunday, Blue (1993) by Derek Jarman is shown as part of a broader program dedicated to the British filmmaker. Entirely in Yves Klein Blue, his final film is a poetic reflection on living and dying with AIDS, featuring readings from his hospital diaries and poetry, atop an immersive soundtrack by Simon Fisher Turner and other collaborators. “When attempting a film on AIDS,” Rebecca Jane Arthur writes on Sabzian, “Jarman knew he had to turn the camera inward in order to come out. For the personal to become universal, the colour blue became his metaphor for illness, a metaphor for transcending it.” Blue asserts the transience of physical presence and life experiences, amplified by the absence of images and a focus on time, memories, and poetry. Much like life, Blue is a snapshot – something that is both intensely present and quickly passing. “In time, no one will remember our work,” Jarman forecasts. “Our life will pass like the traces of a cloud. […] For our time is the passing of a shadow.”

Week 10/2025

“I don’t know if you’re a detective or a pervert,” Sandy throws at Jeffrey in Blue Velvet – a line emblematic of the cinematic world David Lynch built throughout his oeuvre. The filmmaker, who passed away on January 16, needs little introduction. With Eraserhead, Twin Peaks, and Inland Empire, he remains one of cinema’s true inventors, crafting a singular world shaped by the duality of American reality. “This is the way America is to me. There’s a very innocent, naive quality to life, and there’s a horror and a sickness as well.” Screening this week at Cinema ZED, Blue Velvet unfolds in the fictional town of Lumberton, an idyllic suburb where boyish Jeffrey discovers a severed ear, pulling him into a surreal nightmare of violence and obsession. For Lynch, no matter how unsettling his stories, they always followed a strict internal logic: “As soon as you step one foot forward into that story you realize that this world has rules, and you have to follow them, or the audience will sense that you’re doing something dishonest. That’s part of being true to your ideas.”

On Wednesday, CINEMATEK will screen Jean Grémillon’s Lumière d’été. To this day, Grémillon remains one of the least known French filmmakers. Despite Jean Douchet noting in a 2013 interview that “Grémillon was the greatest French filmmaker of the 1930s-50s, alongside Renoir,” he was not included in the names defended by the French critic and his Cahiers-colleagues at the time, such as Bresson, Becker, and Ophuls. “Grémillon was forgotten in the passionate movement that Cahiers had in its grip, but he was never attacked.” Made in the zone libre during the German occupation in World War II, when many French filmmakers were in exile, Lumière d’été transformed from a censored film into one of the most important works of French cinema. “A dance of passionate love, carried by the poetry of the dialogues, written by Prévert and Laroche,” according to the Cinémathèque Française.

Chantal Akerman’s Je tu il elle and J’ai faim, j’ai froid will be shown together this Sunday at De Cinema, two films that have an autobiographical starting point but simultaneously deviate from it through their fictional transformation in mise-en-scène. In Je tu il elle, a young woman, played by Akerman, voluntarily locks herself in a room before venturing into the world, struggling to either conform to or break away from the norms of adulthood. In J’ai faim, j’ai froid, two Belgian teenage girls run away to Paris. For Akerman, it was a depiction of her own experience as an outsider in the French capital. “I come from a country where French is also spoken, from a capital city as well. Everything could be the same, but everything is different – it is also this difference that I would like to show.”

Week 5/2025

Brussels’s Cinema Nova presents a mini cycle of American filmmakers Bill and Turner Ross, showcasing an oeuvre that straddles the line between fiction and documentary to create fragmented portraits of everyday America. On Sunday, they screen Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets (2020), a film chronicling the final night of a Las Vegas dive bar. Shot the day before Donald Trump’s presidential election, the brothers captured 18 consecutive hours in an active bar. Yet, as Nick Pinkerton noted, certain “quiet acts of cinematic imposture” underpin the film: the bar, which is in fact located in New Orleans, isn’t actually closing and the main characters are played by actors. Along with the regulars and staff on screen, they form a secretive plot that defines the film.

As part of their Classics program, CINEMATEK is screening Victims of Sin (1951) this week. A highlight of “the golden age of Mexican cinema,” the film features Cuban dancer-actress Ninón Sevilla in the lead role. Sevilla made quite an impression In the then cinephile circles of Cahiers du Cinéma. Robert Lachenay, a pseudonym for François Truffaut, wrote: “With her inflamed gaze, fiery mouth, everything is elevated in Ninón (the forehead, the eyelashes, the nose, the upper lip, the throat, the tone when she gets angry), the perspectives flee vertically like arrows shot[.]” Set in cabarets, with elaborate music and dance sequences, the film is one of the finest examples of the caberatera-film, a subgenre of the popular “prostitute melodrama”. Now considered one of the greatest Mexican filmmakers of the 20th century, a notable anecdote about Fernández is that, after fleeing Mexico in 1923 following a failed revolutionary coup, he settled in Hollywood, where he notably served as a stand-in for actor Douglas Fairbanks.

A few years ago, a handful of films by Hong Kong filmmaker Wong Kar-Wai were digitally restored and are now being re-released. Known for his lyrical and melancholic portrayal of urban love and relationships – often elliptically told, brightly neon-coloured, with music video-like techniques such as slow-motion, speed-ups, or colour collages – Happy Together presents a portrait of a broken relationship, with Tony Leung and Leslie Cheung playing a couple who travel to Buenos Aires. “To me, Happy Together applies not only to the relationship between two persons, but also the relationship between one person and his past. If people are at peace with themselves and their past, this is the start of being able to be happy with somebody else.”

Week 21/2024

Three years before the film was released in theatres, Chantal Akerman made a making of for her own Golden Eighties (1986). On Thursday, Cinema Palace will show the not often screened Les années 80 (1983) followed by a conversation with the film’s composer Marc Hérouet. Akerman had long had a dream of making a musical but obviously needed sufficient budget to do so. Partly to convince financiers, Akerman came up with the solution of making an edit of the rehearsal footage before the actual film was made. Yet, Les années 80 is more than a mere working document. Starting on a minutes-long black screen, we hear an actress repeating the same sentence, searching for the right intonation. What we get to see is the actual work that a film requires, how finding and scraping rhythm – “a love battle with reality and its elements” with Akerman herself jumping in and out of frame, directing, acting and singing (!) – can eventually lead to fiction.

While the destruction of Gaza continues relentlessly, Cinema Nova has the Israeli filmmaker and theoretician Eyal Sivan, who in his films, texts and interventions has always been critical of the Zionist politics of his homeland, as a guest this weekend. On Saturday, Nova screens his Izkor – Slaves of Memory (1991), a film about the orchestration of collective memory. Izkor – which means “remember” in Hebrew – looks in depth at this imperative that is imposed on Israeli children. During the month of April, feast days and celebrations take place one after another in Israel. School children of all ages prepare to pay tribute to their country’s past. The collective memory becomes a terribly efficient tool for the training of young minds. Then on Sunday, Nova shows another film by Sivan: Common State, Potential Conversation 1 (2012), which stages a virtual conversation between Arab-Palestinians and Jewish-Israelis, all “children of the country,” followed by an online discussion with Eyal Sivan and activists from the Israeli-Palestinian movement A Land for All who, from 2012 onwards, have been advocating the idea of one state for two peoples.

Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed is a 1926 German animated film by Lotte Reiniger and is the oldest surviving animated feature film. Made with a silhouette animation technique Reiniger had invented, using cardboard figures and thin sheets of lead under a camera, the film tells the story of Prince Achmed, who steals a magic horse from a magician and goes on an adventure. On Sunday morning, the colourful film will be screened at Le Cercle du Laveu as part of their Ciné-Enfants programme.

Week 12/2024

Every year, the Flemish Audiovisual Fund (VAF) awards a series of Wildcards, a starting budget for graduating filmmakers to make a new short film. Fourteen films were submitted in the Filmlab category which represents more experimental work. On Monday, ArtCinemaOFFoff will present five graduation films from KASK in Ghent and LUCA in Brussels, that competed for the Filmlab Wildcard. The filmmakers will all be present to elucidate the film that brought their school careers to an end.

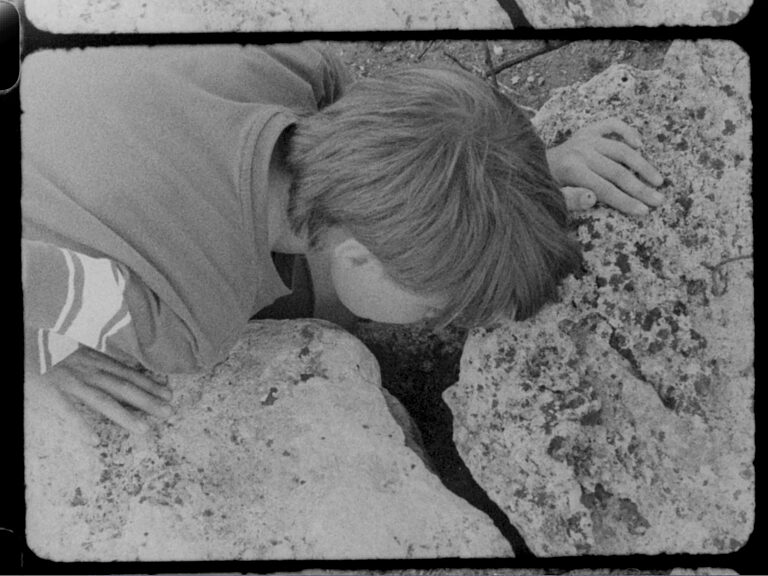

Chantal Akerman, too, once started her career at a film school, namely INSAS in Brussels. To apply, she first had to pass an entrance exam. Asked about his favourite films of 2023, Pedro Costa’s answer was short and clear: “Nothing moved me more than the 4 four-minute films that Chantal Akerman shot in 1967… as her application to the INSAS.” Akerman’s actual debut, only recently discovered, thus consists of four short films, shot on 8mm, silent and in black-and-white, in 1967 in Brussels and Knokke. They are screening on Friday at CINEMATEK, as part of the Akerman retrospective, together with Saute ma ville (1968) and L’enfant aimé (1971). Akerman was allowed to start INSAS, but it was no unqualified success. After a few months, she quit. “Nobody took me seriously at that school,” she said. “They just laughed at me. I realised that I had to make a film to earn any respect at all. So I went to work for a bank, just long enough to finance a short film, which I shot when I was 18.”

Just like Akerman, Jocelyne Saab didn’t study film, nor did she follow the classic path of a filmmaker. Born and raised in Beirut, Saab was invited in the 1970s by artist Etel Adnan to work as a journalist. Unlike most war reporters, who must travel to war zones to pursue their profession, war came to Saab’s native Lebanon in 1975. That same year saw the beginning of Saab’s filmmaking career with Lebanon in a Whirlwind, an account of the various forces and interests behind the incipient conflict. Saab’s chronicling of the horrors of the war – particularly in her remarkable “Beirut Trilogy” – is unequalled in both its ethical integrity and emotional impact. In the four short films screened at De Cinema on Wednesday, we follow traumatised children playing war, teenagers aspiring to become suicide bombers and women fighting for education and freedom. And we return to her childhood home that was completely bombed to the ground. “Each time I made a film, it was in a given political period; each time I had a political objective, my films couldn’t just be without orientation. That’s not sentimentality. Through a form of sensibility, a political problem emerges.”

Week 5/2024

On Wednesday, De Cinema welcomes Mohanad Yaqubi for the screening of R 21 aka Restoring Solidarity (2022), a film that takes a collection of 16 mm films on the Palestinian struggle by militant filmmakers from various countries as its starting point. Dubbed in Japanese to be shown to a Japanese audience, the films highlight the internationalist scope of militant filmmaking in the period 1960-1980. Made up in an array of styles, formats and languages, Yaqubi draws on this material for a film that can be seen as a possible epilogue. He shows how two very different peoples can connect through images, but he also proposes to contemplate the narrative of the Japanese solidarity movement with Palestine during a transformative political period.

CINEMATEK is screening Michael Haneke’s debut feature, Der siebente Kontinent (1989), on Friday. The first part of his ‘Glaciation Trilogy’ – together with Benny’s Video (1992) and 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance (1994) – tells the story of an Austrian family, caught up in their daily routine, planning to move to Australia. Behind their apparent calm existence, however, they are planning something sinister. “The film is the story of the price of conformity,” Haneke said. “[The family] destroys the things that have destroyed them in the same painful way that they created this universe that now smothers them. This is the real tragedy because all the destruction that they provoke is not a deliberate act. It cannot liberate them… It’s not a revolutionary film, it’s a bitter film.”

Also on Friday, there’s a focus on the production and distribution company General Films at Cinema Nova. The team of Nova retrieved thousands of film reels from the cellars of General Films, which was founded in the 1960s by Jean Querut and later taken over by his son Pierre Querut. A Belgian equivalent of France’s Eurociné, it also co-produced films by Jean Rollin and Jess Franco. Nova looks back at General Films’ history in the company of Pierre Querut’s younger brother, Jean Querut, artists Katleen Vermeir and Ronny Heiremans, who made two videos about Pierre for an installation in 2004, and the historian of film techniques Jean-Pierre Verscheure, who was introduced to General’s small family business as a teenager.