(Re)Discovering Charles Dekeukeleire

I. Introduction

The parentheses in my title arise from the fact that Charles Dekeukeleire, a largely forgotten Belgian experiment filmmaker of the late 1920s, had only small recognition in his own day. Hans Scheugl and Ernst Schmidt, Jr., in their admirable reference book, Eine Subgeschichte des Films: Lexicon des Avantgarde-, Experimental-, und Undergroundfilms, say of his films: “They were so advanced in their formal means, so far ahead of their time, that they left behind the puzzled contemporary critics.”1 There were in fact a few contemporary Belgian writers who discussed Dekeukeleire’s films with insight, but certainly this minority response was not enough to insure his work a place in cinema history after he turned to documentary filmmaking in the 1930s.

I first encountered Dekeukeleire’s name in researching a study of European avant-garde styles of the 1920s. The journal Close-up refers several times to his films, Witte Vlam and Histoire de détective, so I put them on my list of films to see. Several archives I visited had no prints, but the Royal Film Archive of Belgium had not only these two, but also two earlier films called Combat de boxe and Impatience – these four constituting Dekeukeleire’s entire silent experimental output. After watching the four, I found myself in a situation that comes but rarely to researchers. Having included Dekeukeleire’s films only through a desire for completeness and knowing virtually nothing about them, I had the pleasure of seeing two good films and two masterpieces. I write about them here not with the desire to tantalize readers with unseeable films, but in the hope of generating interest which might lead to a wider availability of Dekeukeleire’s work.

II. Dekeukeleire and His Situation

Belgium in the 1920s occupied much the same minor position in the world film market as it does currently. The main difference seems to be that, while today there is very little commercial filmmaking in that country, in the silent period there was none at all. Belgium was supplied with films primarily by the United States (which had dominated the world market since World War I) and France.

As in most of the non-film-producing countries of Europe, there grew up in Belgium during the twenties a ciné-club movement that fostered amateur production. The first club formed, the Ciné-Club de Belgique, was modeled on the initial French ciné-club started by Louis Delluc. The Ciné-Club de Belgique began in June of 1921 and went on sporadically for several years, meeting whenever a theatre in Brussels was available. It also published the Revue Belge du Cinéma in 1921. Various other groups attempted weekly screenings, but finally in 1927 the movement gained some real strength. Several enthusiasts founded the Club du cinema, housed in the Palais des Beaux-Arts. It’s “Studio” theatre copied the Ursulines and Vieux-Colomier in Paris by selling tickets to the public—thus becoming Belgium’s first “art-house” cinema. Several other towns had ciné-clubs by the end of the decade, including one in Ostend.2

Heading the latter was a young man, Henri Storck, who began making films in the late 1920s. His short documentary, Images d’Ostende, is an impressive study of the harbor town and bears some resemblance to Joris Ivens’ early work. Storck was to become a major documentarist, one of the two key Belgian filmmakers to emerge from the twenties. The other was Dekeukeleire.

Dekeukeleire was born in 1905. He received a classical education, studying Greek and Latin in college and graduating in 1922 or 1923, at the age of 18. At this point his saw Delluc’s Fievre and Abel Gance’s La roue and became interested in the cinema.3 He worked as a film critic, publishing his first piece, a review of Jean Epstein’s La belle Nivernaise, in the French journal Cinéa, in 1924. In Belgium, he wrote for various art journals. He began making films himself in 1927, the same year as the flowering of the Belgian ciné-club movement, upon which he depended to a considerable extent for support. His silent experimental films were: Combat de boxe (1927), Impatience (1929), Histoire de détective (1930), and Witte Vlam (also called Flamme blanche, 1930). There after he had a long career as a relatively prominent documentarist.

During this brief period as an experimentalist, Dekeukeleire set himself up in as independent a set of production circumstances as he could manage. He owned his own 35mm camera and lighting equipment, and he used bedrooms and sheds as studios. His friends scripted and acted in his films, and he served in all other production roles: “I do everything myself: I buy the raw stock and when it leaves me, it is a film. I direct, I operate and I develop myself.”4 He prided himself on his anti-establishment situation and his refusal to compromise. His career during the late twenties recalls that of Carl Dreyer, whose uncompromising attitude limited his ability to work. In fact, Dekeukeleire admired Dreyer greatly. Real film artists, Dekeukeleire considered, could not work in commercial studio conditions: “That is the case with Dreyer, it is true, the most independent of all, who has not produced more than two films in five years.”5 Dekeukeleire delighted in describing to interviewers his primitive, improvised production situations, and especially how little his films cost to produce. Few directors in that period before government and foundation grants could so well have fit the label “independent filmmaker.”

Indeed, Dekeukeleire’s career seems to define the outer limits to which a filmmaker could go in the silent period with virtually no support. After four experimental films, it proved impossible for him to continue filmmaking in the same isolated way. To a certain extent we can say that Dekeukeleire was born before his time – not in the usual sense that audiences were not yet prepared to understand his films (although this is true – I think audiences accustomed to Snow, Conrad, and structural filmmaking probably have a better preparation for Dekeukeleire’s work than his contemporaries did). Rather, the filmmaking establishment was not set up in ways which could accommodate people like him. He could not accept the compromise of working within commercial feature filmmaking on a commission basis, as some of the Germans did. Filmmakers like Richter and Fischinger could do shorts or special sequences for the big German concerns while continuing their own work on the side. But Belgium had no commercial industry, and Dekeukeleire’s experience in dealing directly with the large exhibitors on Combat de boxe closed that route for him, as we shall see. In France, the experimentalists worked within the mainstream film industry to a considerable extent, alternating popularly oriented films with their more avant-garde work, or depending on the well-developed French ciné-club system for commissions. Dekeukeleire followed this latter tack, but his films failed to break past Belgium and France into the broader experimental market (such as the London Film Society) to any extent. A screening of Impatience at the 1929 Film und Foto exhibition in Stuttgart seems to have met with an indifferent reception.

From 1932 to 1934, Dekeukeleire served as the Belgian correspondent for a French newsreel produced by Germaine Dulac. Then he set out for the Belgian Congo to do a documentary. His stay in Africa seems to have been a turning point for Dekeukeleire. A generous interpretation would state that he changed into a liberal humanist director of documentaries, a path he pursued until his death in 1971. But to an admirer of his silent experimental works, the change is a depressing one. I have sampled a few of his documentaries, and they have none of the fascination imparted by a Resnais or a Marker. Rather, they are exactly the kind of films a business firm, a national tourist board, or a charity hopes for when giving out a commission: well-made, reasonably interesting, unexceptional in both sense of that word. He remained somewhat leftist, favoring subjects that allowed him to show the dignity and beauty of human labor (as the 1938 title Chanson de toile suggests). He also refused to cooperate with the occupation forces during World War II. His entire output from the war years was a few short films, done for Belgian charities. In all, he made eighty-three films, in addition to newsreel and television work, according to his own statement,6 gaining himself an honored but minor status in documentary film circles. He died in 1971.

III. The Films

Combat de boxe and Witte Vlam, although both interesting and well-made works, are less original and startling than the two works that came between them. I shall discuss these briefly, then spend the remainder of this essay on Dekeukeleire’s two masterpieces, Impatience and Histoire de détective.

Combat de boxe resembles French traditions of experimental filmmaking in the 1920s. Taking a simple event, a brief bout between two boxers, Dekeukeleire abstracts it through the use of numerous filmic tricks – negative footage, superimpositions, jump cuts, and extremely rapid rhythmic cutting. He shot the film in his own bedroom, using a sheet stretched on the floor as the canvas of the ring, surrounded by ropes. Two actual boxers took part. Using Kuleshov-effect editing, Dekeukeleire inserts long shots of the crowd apparently looking on. Through most of the film, the crowd shots appear in negative, while the boxers are on positive stock. At times, the filmmaker superimposes the boxers’ faces in positive over the negative crowd images. Several stretches of the film are rhythmic series of quick shots with sections of black leader, ranging from eight frames down to an occasional single-frame shot. By alternating a close-up and a medium close-up of a clenched fist, Dekeukeleire achives a pulsing effect, as if the hand were striking toward the audience. This literalist approach to aggression against the spectator would become less overt in his later films, where the films of the films themselves take the aggressive part. In general, Combat de boxe is Dekeukeleire’s least distinctive experimental film.

Dekeukeleire atttempted to get Combat de boxe into commercial distribution in Belgium. Paramount’s theatre in Brussels, the Coliseum, contracted to use it as a short before the feature presentation, Chang. The exhibitor was to pay Dekeukeleire 750F; apparently the filmmaker was naive enough to agree to this by verbal contract only. After several days of screenings, the exhibitor cut portions of the print, and Dekeukeleire sued to have the showings stopped and to get his 750F plus 10,000F in damages. The case dragged on for some time and was decided against Dekeukeleire in August 1928. He appealed and lost again in 1931.7

He met with better luck outside commercial distribution, in the ciné-club circles. In early 1928, the Théâtre des Ursulines in Paris was showing Germaine Dulac’s La Coquille et le clergyman. Due to hostile demonstrations by scenarist Antonin Artaud’s friends, the theatre was forced to take the film off the program; Combat de boxe replaced it.8 Dekeukeleire’s film received favorable reviews and ran for three months. From that point on, he worked entirely within the ciné-club circuit for exhibiting his experimental films, but even this did not guarantee his subsequent work particularly sympathetic responses.

Although Dekeukeleire’s fourth film is often called Flamme blanche, its actual title is in Flemish, Witte Vlam. (Dekeukeleire was of Flemish ancestry, but this is the only “Flemish” film of the four experimentals.) The filmmaker called this work “a look backward,”9 since it lacks the radical experimentation of Impatience and Histoire de détective. Here instead a considerable influence from Vertov and Eisenstein is apparent, with “Russian” framings and cutting dominating the non-documentary portions.

The narrative concerns a peaceful demonstration by the Flemish People’s Party at Dixmude, an actual event which Dekeukeleire filmed. To this he adds a specific story line about one of the demonstrators, a butcher who is injured when police ride through the crowd. He flees to his home and is subsequently arrested while hiding in the barn. The “white flame” of the title refers figuratively to the immense white banner which moves in the wind in the demonstration scene and final shot. Dekeukeleire described the title as the “poetic equivalent of pure revolt.”10

In the opening scenes of the crowds in Dixmude, Kekeukeleire inserts several close-ups of workers’ faces, shot against the sky in Soviet fashion When the police arrive, he suggests the action mainly through a series of static close shots and quick cutting. After an extreme long shot of the crowd from high above, there follows a close-up of the protagonist’s face against white, then a close-up of gloved hands holding a horse’s reins. After a brief repetition of each of these framings, Dekeukeleire introduces a low angle close-up of a gendarme’s face against white. Then, through a series of thirty-six rapid shots of sword blades, riding crops, and the butcher’s apprehensive face, the scene builds up to the single medium close-up sot in which he is beaten. The overall effect has little of the epic qualities of the Soviet films with their large riot and demonstration scenes. But Dekeukeleire, with his more limited means, uses similar montage principles to build up the effect of the conflict, without ever trying to make the close shots appear as realistic segments of the space shown in the documentary long shots. The film is one of the closest imitations of Soviet montage style done in Europe during the silent period.

Witte Vlam seems to have had limited circulation. It was on the program of the Congrès du cinéma indépendent, held at Brussels from November 28 to December 1, 1930. (This was the second such congress, the first having been the La Sarraz meeting of 1929, made famous in part by Eisenstein’s participation.) There may have been other showings, but the film attracted relatively little attention.

Dekeukeleire’s second work, Impatience, seems to me a remarkable work, largely inexplicable through its historical context. Certainly Dekeukeleire was familiar with the major avant-gardists of his day. In a 1933 article he said, “The most important films of this first period will be those of Eggeling, Richter, Ruttmann, and Fernand Léger’s Ballet mécanique which is perhaps the masterpiece.”11 Impatience’s closest antecedent may indeed by Ballet mécanique, the only 1920s film it calls to mind, but even there the resemblance is minimal. Ballet mécanique is an ingratiating work, while Impatience seems calculated to alienate its spectator. It is about three times as long as the Léger-Murphy film, uses only a few objects, and has little or no humor. Dekeukeleire structures it around rhythmic editing and relentless repetition of this small number of elements, with limited variations. The film credits introduce “Four characters”:

The Mountain

The Motorcycle

The Woman

Abstract Blocks

and adds, “The human character is played by Yonnie Selma.” This suggests that the three non-human elements will be somehow anthropomorphized, but in the actual event, the woman becomes more of a visual object.

The film, which runs about thirty-six minutes, consists of repetitions of these four elements. Although the suggestion is strong that the woman is riding the motorcycle, the four elements always appear in separate shots. Dekeukeleire films parts of the motorcycle, parts of the woman’s body, and the abstract blocks in a studio against a white background. The woman and machine vibrate as if jarred by the motor and road bumps, but the overall effect never simulates real driving. The mountain appears in violently moving handheld camera shots, vaguely suggestive of some of the quicker movement in La région centrale.

Impatience opens with a frontal close-up of the woman in cycling gear (Fig. 1). Her head vibrates as if she were on a cycle. Following this comes the most extreme and mechanically rhythmic set of repetitions in the entire film: two medium close-ups of portions of the machine also vibrating (Figs. 2 and 3). These appear in alternation – five of each. Each shot is 53 frames (at silent speed, about three and a third seconds each). Thirty-three frames of white leader seem to mark an end to this segment, yet the same two shots reappear, alternating again with ten of each shot. This time each shot is 26 frames long, about half the previous length. After these, the first rolling handheld mountain shot occurs.

So far, in spite of the lack of establishing shots, the film seems to hint at a potential narrative situation—a woman going through the mountains by motorcycle. Yet Dekeukeleire simply goes on with various framings of parts of the machine and the woman’s face and body. At her second appearance, the woman does not wear the cycling clothes. For the rest of the film, she appears sometimes clothed, sometimes nude; in the nude shots, her body sometimes vibrates, but not always. Dekeukeleire thus breaks down the initial hint of a narrative situation by repeating elements with no development outside of a graphic and rhythmic play. The woman seems to react: her face registers fear, desire, happiness, and other emotions at various times, yet these expressions are stripped of their status as responses by the fact that we never see a cause for them. (Again, Ballet mécanique comes to mind, with its close-up of a woman’s face, which changes expressions as she passes a card in front of it.) Similarly her clothed or nude state seems only to follow graphic patterns; it makes no narrative sense. Contemporary reviewers seemed determined to recuperate the film as a narrative, however tenuous. Several describe the film as a woman impatiently traveling to meet her lover – a suggestion which has no basis in the film itself. (This interpretation depends largely on the title. When the film appeared at Stuttgart, it went under the title Variationen der Ungeduld [Variations on Impatience], perhaps to orient the viewers toward the film’s abstract qualities.)12

Yet there is no doubt that the film is bound up with eroticism. To a certain extent the nudity, mild and “aesthetic” though it is, will inevitably suggest the erotic, as do some of the woman’s facial expressions. Beyond this, however, the film’s style and form embody this quality. Ravel’s Bolero, in spite of its lack of subject matter, is an erotic work in this same sense. (Indeed, imagine Bolero done in twelve-tone, twice as long, and with no build in volume, and you have some sense of the maddening fascination of Impatience.)

After a lengthy segment which uses only the cycle, mountain, and woman, Dekeukeleire brings in the “abstract blocks.” These are three thin, rectangular objects, fastened parallel to each other, which swing slowly or quickly at various points. Impatience inserts shots of these blocks at intervals among the repetitions of the three other “characters.” At one point, a shot of the blocks swinging in a slow arc (Fig. 4) is followed by a medium close-up of the woman, her neck rigid, swinging her head and shoulders in a similar arc (Fig. 5). This is perhaps the most explicit equation the film makes of the human figure to an abstract object, but clearly such an abstraction governs the graphic patterns of the whole film.

By this point in his career Dekeukeleire had seen the Soviet films which were beginning to pour into Europe in the late twenties. While Combat de boxe remains largely within the western European avant garde of the period, Impatience goes much further with aggressive conflict editing (rapid jump cuts of the same object with small variations, juxtapositions of one shot with the same shot turned upside down, and so on). He also uses barrages of single-frame montage, but with neither the narrative motivation of Gance nor the machine-rhythms of Vertov. For sheer aggression against the audience, Impatience quite possibly has not its equal in the era before the New American Cinema. Nor does this aggression result from the subject matter. During this same period, the Surrealists were making their films. Buñuel’s Un chien andalou, with its eye-slitting, severed hand, and dead donkeys confronted spectators directly with shocking images. Yet Impatience avoided such tactics. Rather, Dekeukeleire builds audience frustration into the film’s form and style. “Impatience” as a title suggests as much the audience’s state as the character’s. The mounting frustration of this film, and later of Histoire de détective, constitutes their aggression.

Impatience, not surprisingly, encountered considerable resistance from audiences. It premiered on March 13, 1920, at the Ostende ciné-club, on an otherwise non-experimental program consisting of a Felix the Cat cartoon, a documentary on Chad, and a revival of Wachsfigurenkabinett – hardly the context to prepare spectator’s for Dekeukeleire’s film. The filmmaker’s friend Maurice Casteels (who was to script his next project) tried to soften the blow by comparing the film to a sonata, a symphonic poem, and, with considerable insight, “an Archipenko sculpture in movement.”13 Henri Storck also prepared the way with a sympathetic analysis in a local newspaper several weeks in advance.14 Nevertheless, Dekeukeleire, who was present at the screening, was treated to uncomprehending laughter. The film was seldom shown in Belgium, although it appeared along with Combat de boxe on the Filmliga program in March 1930, to accompany the premiere of Histoire de détective. The film fared somewhat better in France, where Dekeukeleire showed it in April 1029. There it received mixed reviews, but ciné-club audiences at least took it seriously.

Apparently in response to the adverse audience reactions to Impatience, Dekeukeleire decided to try a new approach. After the French premiere, he told a Parisian interviewer:

Impatience closes a period of my work. Sensing myself too separated from the public and the exhibitors in practicing abstract filmmaking, I plan, in my upcoming project, to use a scenario of a more realistic spirit, always maintaining in its story the serious plasticity and high rhythmic sense that I have sought and still seek.15

The tone here is a bit pompous, but Dekeukeleire did manage to accomplish his goal in his first narrative film, Histoire de détective. The film contains devices familiar from Impatience: an obsessive repetition of a small number of elements, handheld movements over landscapes, and rhythmic editing. But several new structures shape this material. The film presents itself as the record of a case made by a detective, T, who uses the motion-picture camera as his investigative tool. Aside from a few short scenes of T at work in his developing, editing, and viewing rooms, all the shot (except intertitles) purport to come from T’s work. Histoire de détective is thus a film within a film, and the intertitles tell us the story, not simply of the case, but also of T’s filming of the case.

Contemporary reviewers’ descriptions of the film were oddly similar and all highly misleading. (I suspect they wrote up their plot descriptions from the same program summary of the action.) But there is also some evidence that Dekeukeleire recut the film after its initial screenings. Virtually every review mentions a “dance of apples,” evidently a pixillated scene; the general confusion as to its purpose may have led Dekeukeleire to eliminate it. Also, the film is divided into parts by numbered intertitles. The original negative in the Belgian archive contains scenes numbered 1-5, then skips to 7, then “4Bis,” then 9-12. Clearly Dekeukeleire was playing with the numbering, with the introduction of “4Bis,” but this would have made it all the easier to eliminate sections. As it is, the film is a short feature.

Based on the existing negative, the story concerns J. Jonathan, who is in a neurasthenic state. Mme. Jonathan has, at the beginning of the film, just hired T to discover the reason for her husband’s condition. The film shows shots of Jonathan in Brussels. He then goes to Ostende to recover, but he is bored there. He sets out to return to Brussels but goes on to Luxembourg, is bored again, and goes to Bruges, where he stays for some time, making frequent trips to the seaside. Dekeukeleire inserts series of shots of Mme. Jonathan, in modernist clothes, energetically talking on the phone, listening to the gramophone, writing, and giving a speech. She is portrayed as a frenetically up-to-date woman. Finally Jonathan wanders through a hilly countryside and decides to build a factory among its picturesque ancient ruins. His wife concludes that he is now cured; T has succeeded.

There is a strange tension in the presentation of these events in Histoire de détective. The images themselves convey none of the action. All we see are the two characters, and occasionally T, always in separate shots, walking, sitting, speaking into phones. There are no dialogue titles. Dekeukeleire intersperses shots of the characters with numerous shots of buildings and landscapes, often seen upside-down or rolling in extremely jerky handheld movements. He also includes shots of trivial objects – cups, books, pieces of bread – which do not enter causally into the narrative. Instead of conveying the events in accepted silent-film fashion, through as few titles as possible, Dekeukeleire inserts numerous lengthy titles. Virtually the entire narrative depends on these intertitles. The shots between seem so uninformative that they almost come to resemble found footage around which a narrative has been constructed.

Dekeukeleire flaunts this narrative incompleteness from the beginning. The film opens with a lengthy crawl title explaining how “my friend T” has made this film as part of an investigation for Mme. Jonathan. The title states, “This film contains numerous lacunae if one wants to view it as a story like any other. It is a series of psychological documents.” In an early scene, we see Jonathan make out a telegram from Ostende telling his wife he will return home to Brussels. There follows a medium shot of Mme. Jonathan at home, followed by an intertitle: “At certain moments a great influx of jostling travelers makes filming very difficult. Please excuse the lack of clarity.” The shot after this title returns to Mme. Jonathan, reading the telegram, then a rapid montage (sometimes of single frames), first of Jonathan’s face and then of hers. The sequence in which Jonathan travels to Brussels but continues on to Luxembourg consists of:

1. Title: “And”

2. ELS, rolling camera movement over country landscape

3. Title: “the sleeping car which he took”

4. As 2

5. Title “did not let him off at Brussels”

6. As 2

7. Title: “but”

8. ELS, very jiggling handheld shot of mountains

9. Title: “at Luxembourg.”

We next see Jonathan wandering about the countryside, presumably in Luxembourg.

Acting has little to do with such a narrative style. Some non-actor acquaintances played t, M. Jonathan, and Mme. Jonathan. Dekeukeleire’s friend Paul Werrie (the scenarist of Combat de boxe) has described how Dekeukeleire directed his actors in Histoire de détective:

They were made to do a set of things, to pull up the grass on the dunes, for example, but they did not know at all what purpose this would serve. They simply lived, and the camera caught their reflexes. At any price, they did not act, not even “naturally.” From fear of acting, acting was suppressed.16

Histoire de détective is an experimental film which allows narrative in, only to negate it by suppressing, not just acting, but all the visual conventions which the silent cinema had built up to present story material to the spectator. Contemporary reviews consistently rebuked Dekeukeleire for depending to heavily on intertitles. Commentators had long become accustomed to praising films like Der letzte Mann for eliminating intertitles. Little in previous filmmaking could have prepared spectators for a film that deliberately made its images wholly dependent upon an extensive text for narrative meaning. (Indeed, perhaps they took the intertitles at all seriously only because Dekeukeleire has a well-known writer, Maurice Casteels, do the texts, and a prominent artist, V. Servranchx, design the title graphics).

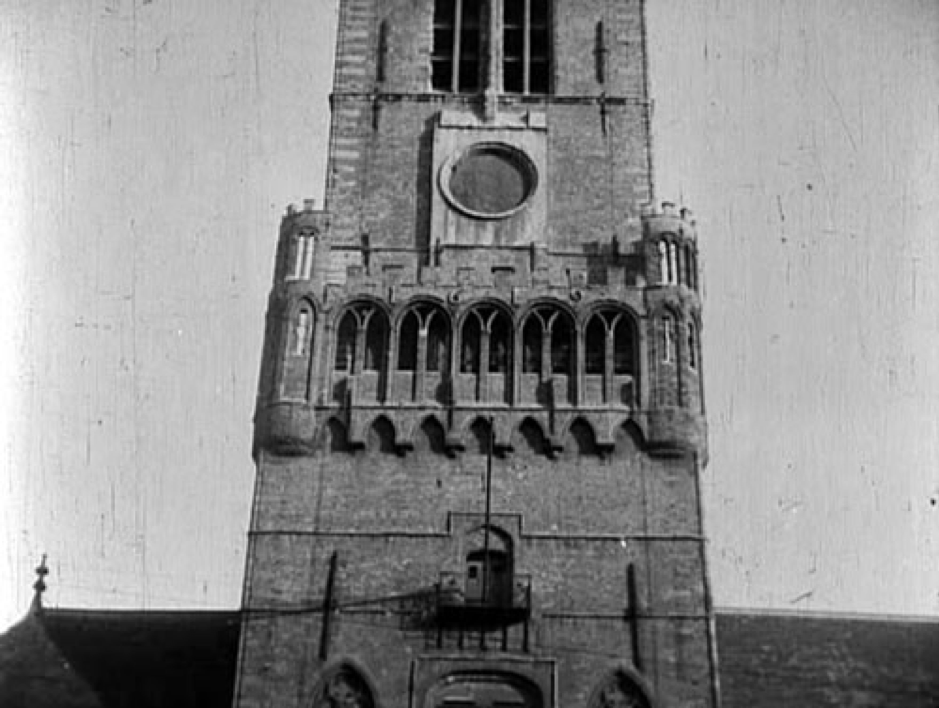

Perhaps the best sequence for illustrating Dekeukeleire’s work against the narrative is Jonathan’s stay in Bruges. Bruges, the capital of West Flanders, is a modern town grown up around a small inner section of beautifully restored medieval buildings, all built amid a set of tiny canals that has given it the nickname, “The Venice of the North.” The sequence begins thus:

1. Title: “Jonathan seeks other scenery.”

2. Title: “T follows him.”

3. LS, a low angle of the Belfry in Bruges (Fig. 6)

4. Title: “Bruges”

5. As 3

6. CU, high angle, an empty coffee cup (Fig. 7)

7. LS, brief (22 frames) shot of Jonathan on an old bridge (Fig. 8)

8. Title: “Jonathan did not see:”

9. ECU, a small map of the old section of Bruges. A pencil marks a spot (Fig. 9)

10. Title: “The Béguinage and the béguines (founded in the 13th Century and which inspired the poet Georges Rodenbach).”

11. As 7, Jonathan sits on the railing of the bridge.

12. As 6, a spout comes in and fills the cup with coffee

13. As 11, Jonathan sitting

14. Title: “Jonathan did not see:”

15. As 9, the pencil moves and marks another spot

16. Title: “The Hôtel Gruuthuuse (built in 1470 and reconstructed often since).”

17. As 13, Jonathan continues to sit

18. As 15, the pencil circles around, moves to center of map

19. Title: “The Hôtel de Ville (founded by Louis de Maele, Count of Flanders, in 1377).”

20. As 17, Jonathan is now smoking

21. As 12, the coffee cup

22. As 20, Jonathan stands and begins to leave the bridge

23. Title: “Jonathan did not see:”

24. As 18, the pencil moves to the southern portion of the old district

25. Title: “The Lake of Love and the swans, recalling the assassination by the Brugians, revolting against Maximillien, of magistrate Pierre Lanchals, who had a swan in his coat of arms.”

26. As 22, Jonathan leaving the bridge

27. As 24, the pencil traces the canals

28. Title: “He did not take a tour in a boat.” On this same card appears “Bruges,” then “The Venice of the North,” then “43 bridges.”

29. As 26, Jonathan stands at the far end of the bridge

The film then intercuts various shots of the bridge and coffee cup with shots of Mme. Jonathan worrying in Brussels. In the shots just listed, Dekeukeleire chips away at his narrative by showing the things his protagonist did not see. (All this is doubly ironic since Bruges’s central district is very small; Jonathan could hardly have been on an old bridge there without seeing some of the sights listed.) Dekeukeleire also lengthens the titles beyond their narrative functioning by adding guidebook phrases to each description.

The overall result of tactics like this is a film which seems almost to have an invisible narrative. The titles make the story line clear enough, but in watching the film the spectator cannot really see the narrative being worked out. The images don’t contradict what the titles present, but only occasionally do they show anything which adds to or really tallies with the verbal descriptions (except in a passive way, as with Jonathan sitting on the bridge as the titles describe him “not seeing” things). I don’t mean to suggest that the film is uninteresting – its violent camera movements and rhythmic montages tend to add some of the qualities of an abstract film. And, as one strains to discover the narrative significance of these shots, their very opacity makes them intriguing.

The irony of all this seems to have been lost on at least some spectators. One reviewer, Marcel Rival, liked the film fairly well, especially its beautifully photographed landscapes; but, said Rival:

It is this beauty, it is this calm, it is this limpid air, this joyous river which De Keukeleire would like to see ruined, broken, infected, dried up for the pleasure of creating there a dam and factory. De Keukeleire does not seem to love virgin Nature much and he prefers a factory creating fumes, misery, pollution, ugliness. He hates trees but cherishes concrete poles.17

Faced with such incomprehension from his small public, Dekeukeleire shifted his tactics once again for his next film. In Witte Vlam, as we have seen, the political subject matter is more overt.

IV. Conclusions

Ultimately Dekeukeleire may seem so modern because, unlike most other filmmakers of his day, he was working mainly against the traditions which then existed. Other independent filmmakers were working to establish genres like pure cinema, or surrealism, or documentary. The conception of film as an art form was barely a decade old, and most people interested in cinema were still caught up in the attempt to explore the medium’s possibilities. Yet Dekeukeleire made one non-narrative film, Impatience, which was nevertheless not pure cinema either. Nor did he present his films as the objects of pleasant aesthetic contemplation, as with abstracts like Ruttmann’s Opus I, II, and so on, Fischinger’s Studies, or Len Lye’s Tusalava.

Perhaps above all, Dekeuekeleire’s two masterpieces frustrated the spectator’s urge toward narrative interpretation: Impatience’s suggestion of a narrative situation which never emerges, and Histoire de détective’s excessive dependence on written texts work upon narrative without either confirming or denying it. This approach has become relatively comprehensible to modern audiences through films like Michael Snow’s ↔ and Wavelength, which also touch upon narrative potentials and then deny them to the spectator. At the time when Dekeukeleire’s films were made, the filmmakers’ sympathizers manly defended them by pushing them toward abstraction (a poem, a sonata). His detractors, on the other hand, battened onto their incomprehensibility as narratives and their pointless repetitions. The failure of the films to fit into recognizable categories with which the spectators could cope probably contributed to his work’s current obscure position. Brought out again today and exhibited to wider audiences, Dekeukeleire’s experimental films could undoubtedly find sympathetic viewers.

- 1Hans Scheugl and Ernst Schmidt, Jr., Eine Subgeschichte des Films: Lexicon des Avantgarde-, Experimental-, und Undergroundfilms, Vol. I (Frankfurt am Main: Surkamps Verlag, 1974), p. 179.

- 2All information on ciné-clubs from Francis Bolen, Histoire authentique, anecdotique, folklorique et critique de cinéma Belge depuis ses plus lointaires origines (Brussels: Memo and Codec, 1978), 83-86.

- 3R. S., “Un cineaste belge: Charles Dekeukeleire,” Le Moustique (March 14, 1938 – penciled date), n.p. Clipping file.

- 4A. F., “Charles Dekeukeleire nous parle de ses debuts,” no source (June 4, 1940 – pencilled date), n.p. Clipping file.

- 5Charles Dekeukeleire, “Explication de la crise du cinéma,” Pt. II XXe siécle (Brussels, June 30, 1933), n.p. Clipping file.

- 6Charles Dekeukeleire, “Biographie,” typescript resumé, clipping file.

- 7Correspondence between Dekeukeleire and his lawyer, clipping file.

- 8Geo. Charles, “Combat de boxe, le film de notre collaborateur devant le public parisien,” Dernièrs Nouvelles (Brussels?, March 30, 1928), n.p. Clipping file.

- 9Ch. Delpierre, “Entretien avec Dekeukeleire,” Les Beaux-Arts (January 9, 1031), n.p. Clipping file.

- 10Ibid.

- 11Dekeukeleire, “Explication de la crise du cinéma.”

- 12A. Kraszna-Krausz, “Exhibition in Stuttgart, June, 1929, and Its Effects,” Close-up V, 6 (December 1929), p. 460.

- 13Club du cinéma, “Programme de la 36ième séance,” (March 13, 1929). Clipping file.

- 14Henri Storck, “Au Club du cinéma,” Le Carillon (Ostende ?, February 1929 – pencilled date), n.p. Clipping file.

- 15Flouquet, “En dessinant Charles Dekeukeleire,” Aurore (Paris, April 22, 1929), n.p. Clipping file.

- 16Paul Werrie, “L’Oeuvre de Ch. Dekeukeleire, or le lyrisme documentaire,” Reflets (Brussels, April 1940): 7. Clipping file.

- 17Maurice Rival, “Histoire de détective,” Film-Revue (n.d.), p. 10. Clipping file.

Images (1) to (5) from Impatience (Charles Dekeukeleire, 1928)

Images (6) to (9) from Histoire de détective (Charles Dekeukeleire, 1929)

All translations by Kristin Thompson.

This article was originally published in Millennium Film Journal, nos. 7/8/9 (Fall-Winter, 1980-81). The text can also be found on David Bordwell’s website on cinema.