Voyage à Paris

To Make Images Speak

Voyage à Paris, an Antwerpen 93 [in 1993, Antwerpen was the official European Capital of Culture] and TV-Twee production by Jef Cornelis (director) and Rudi Laermans (script), was made in the context of the project “Discourse and Literature”. Publications on paper as well as one on magnetic tape, publications using printed letters as well as one using filmed images. But the intention remains the same: an intellectual essay. No fiction, no reporting, but commentary, considerations, reflections, connections.

Audiovisual material is gradually taking on very different forms of consumption. Voyage à Paris was broadcast by the national television channel, was screened before live audiences in Antwerp and is for sale as a video cassette. So, in addition to one-off public screenings, private video viewing has become possible too. This has become quite common.

TV-programme producers occasionally try to make their works available for repeated viewing in addition to one-off screenings. As is the case with Voyage à Paris, which is like a beautiful poem you want to read several times, or a piece of music you want to hear several times. This visual essay contains a couple of passages you will remember especially well, transitions that are so intriguing that you will want to further savour them. I deliberately refrain from writing “further analyze them”. Because that would be the kind of interest that operates behind the film’s back in order to discover its constructional secrets. If you want to take a closer look at this essay, however, it has nothing to do with an inappropriate kind of interest, as you immediately notice that certain transitions require extra focused attention. Similarly, you really need to be aware of a sonnet structure; whereas the skeleton of a novel can only be discovered by an objectifying consciousness, because it is supposed to remain covered up.

Voyage à Paris consists of an image track and a sound track. The most wondrous things happen to the sounds; there is a constantly changing relation to the image. In retrospect, I think that has always been one of Cornelis’s main concerns. He doesn't want the sound to support the images in a banal way, wedging the sound between the image and his model. He is constantly cutting away the “realistic” roots of the film images. He doesn’t touch the images themselves, but abstracts and stylizes them, scraping away their documentary nature. Never entirely, but just enough to let the images slip away from realism. The principle may be easy to understand, but its subtle application, the ever-changing nuances in the relationship between sound and image, holds you spellbound throughout the essay’s fifty minutes.

The soundtrack itself is very composed. The remarkable thing is that there seems to be no dominant track, no level against which to set all the sounds. Sometimes there is synchronous ambient sound, but it still sounds artificial between the other types of sound. Music regularly intervenes, but clearly as a quotation that raises a point; as an argument, equivalent to the argument coming from the images. The music is leading a life of its own here; it doesn’t accompany but co-builds the argument. The most striking features are the sound-pebbles that play their barely visible, decomposing role between snippets of other sounds. They most strongly detach the image from the document, opening up the programme to intellectual viewing. The sighs of women, the rustling and clattering all prevent us from passively watching images “of” something; they enable us to consider those images as “about” something. From registration, we thus end up in “discourse”.

I have been deliberately withholding the last type of sound. Dirk Van Dyck reads quotations in a brilliant way, as a real person, and not as a nasty, bodiless glamour-voice that is mere seduction. Quotes from letters written between the end of the eighteenth and the first half of the twentieth century. Letters from foreigners visiting Paris (and not observations by residents). They show amazement, delight, admiration, dismay. You learn that this is a New World for every writer (which, in the nineteenth century, was not the US but that city located a three-hour train ride from us [in Belgium]). This spoken footage from the past does something very different from the images: the images are of the present (generally). The quotes, however, are old. The texts present us with the past of the city; the images show us how people have adapted themselves within that past. While the soundtrack had so far established a kind of perceptual relief, including shadow and depth effects, the quotes read employ a similar mechanism, but now geared towards historicity. Not only is what we see important, but also what we know and are able to imagine. A key maker of architecture films, Cornelis knows better than anyone that a building is a message from the past, that architecture is the time machine par excellence. The texts operate like litmus tests. Place them on top of a film image and right away the parts in which history has taken root light up.

In addition to this vertical axis of sound/image, there are horizontal compartments, namely the succession of sequences. It should be noted that these fifty minutes do not develop a clear argument, do not start somewhere with an introduction and end with a conclusion. The trick of the transitions alone is usually so wonderful that you’re not in need of arguments. For instance, the transition from the café to the clothes shop underneath Benjamin’s text, the transition from boulevard to theatre, from there to Manet and onwards, via a brilliantly positioned bird’s-eye view, back outside, into the city! It’s visual-poetic pleasure of the first order. For connoisseurs, but also perfect for beginners: how to evoke, without a single electronic trick, wonderful nuances across ordinary contemporary film images; how to learn a lot, without a single didactic moment.

‘Voyage à Paris. To Make Images Speak’ originally appeared as ‘Voyage à Paris. Beelden doen spreken’ in Andere Sinema, no 116 (July/August 1993).

With thanks to Reinhilde Weyns and Bart Meuleman

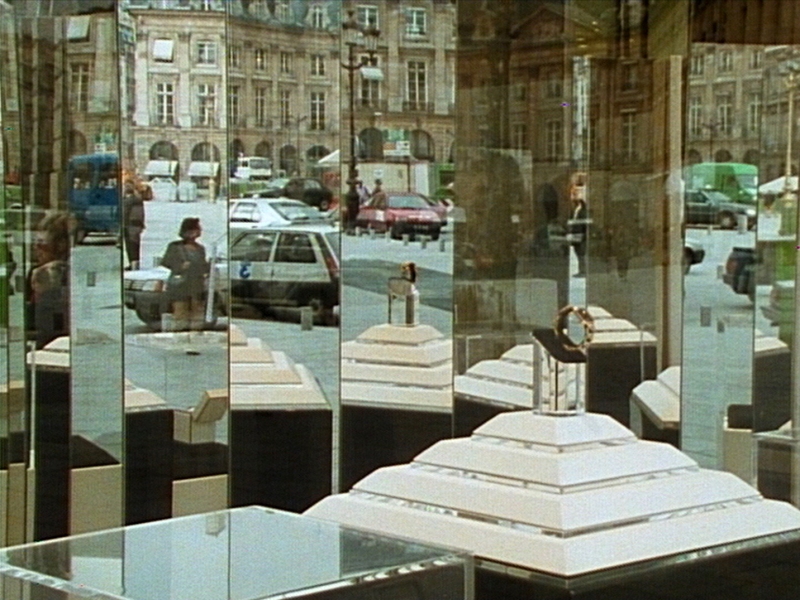

Images (1), (2), (3) and (4) from Voyage à Paris (Jef Cornelis, 1993)

This text is published in the context of the online première of Voyage à Paris (Jef Cornelis, 1993), tonight at 20:30 on Avila. You can find more information on the event here.