Part Eastern philosophy, part gunslinger Western, Quick Billy plays as a “horse opera in four reels” and meditation on the transformation of life to death, conceived for viewing with a single projector to allow the natural pauses between reels.

“[Quick Billy] crowns ten years of Baillie’s lyrical and pastoral film sensibility. (...) He may have achieved the most complete and most satisfactory film, which, through this mysterious openness, permits us to project into it so many incomplete parts of ourselves. (...) I do not expect that suddenly wide masses of people will rush to the Whitney [Museum of American Art] to see Quick Billy. I am realistic enough to know that the majority of the film-going public are still milling in the hallways of Eternal Hollywood. The art of Bruce Baillie is for the lucky, or for the ready, few.”

Jonas Mekas1

Scott MacDonald: When I was looking through your films, the biggest discovery for me was Quick Billy. It's a pretty amazing film, and certainly begs for questions because it’s so diverse. Reel one is very much about morning and creation.

Bruce Baillie: I think that the beginning section is one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen in the movies. I had to get out of bed to make every one of those takes. I was really sick, with hepatitis. [Paul] Tulley would come over, and I would tell him what part of the house I had to go to, and he would help me up. I’d tie a knot in a big beach towel and pull in my liver with it. He’d walk me over to, say, the fish tank, and set the tripod up and load the camera. Then I’d do the take and go back to bed.

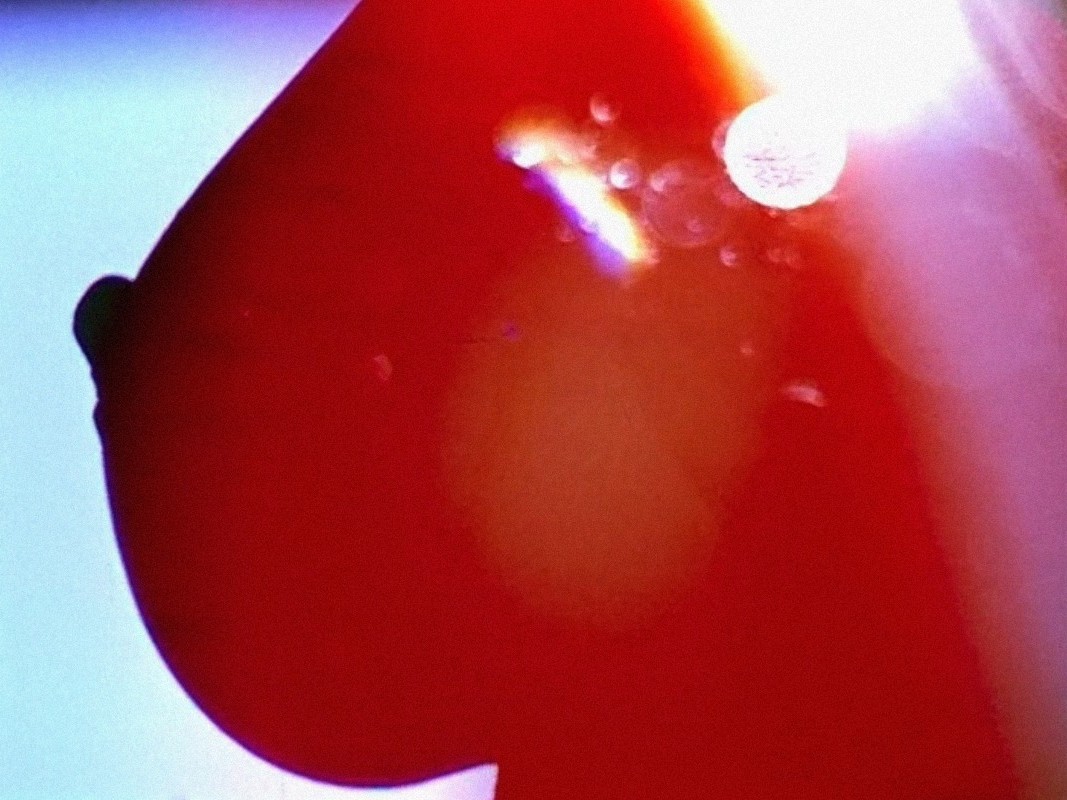

The opening shot of Part One is very mysterious. The spectator never actually sees anything, just a shade of pink that gets a little more dense, then less, over a period of about two and a half minutes. And I'm not sure what I'm hearing: sometimes it sounds like traffic, sometimes like the ocean.

It’s the ocean. Later, there are the sounds of passing timber trucks. (...) That sunlight image that opens Part One was the first roll I shot. I shot Quick Billy on ASA 25 outdoor Kodachrome, I believe. I think it was about the last they had. And I numbered the rolls from one on, just to keep track of them when they went to the lab. (...) That opening is supposed to be the highest moment of illumination in the whole work. I was following the Tibetan description of the time between life and death, and that's either the illumined memory of perfection or the illumined moment of discovery. It can go either way. I never played the film backward, but it was designed so it could run backward or forward. (...) The end of the whole film would be the beginning shot with that pure light.

So that version would move from the mundanery of conventional narrative toward this moment of supreme illumination, like a journey up the chakras?

I was describing my own death experience through the catalyst of hepatitis. I had studied The Tibetan Book of the Dead. There the deceased is on a journey, “the time of uncertainty.” The specters come to us as our own personal cinema: we are obliged to confront the results of our own deeds. It becomes more and more frightening. As I pursued the experience, I found this delightful moment in the beginning which was so lovely; it degenerated into a terrifying but lovely cosmic storm. (...)

The assignment the first time, given to me by the conditions of making the film, was not to make a beautiful film, but rather to make a document about this inner passage, a little-described, but very common, in fact universal, phase of being human: the evolution of consciousness through which every man and woman eventually must go. (...) I think my concept for Quick Billy is almost identical to Stan Brakhage’s Scenes from Under Childhood [1967-70], which explores the “scenes” prior to childhood, the scenes so near that time between being and being. Brakhage was sending me those films at the time I was going through all this, and they were essentially identical to what I was making, I thought.

Bruce Baillie in conversation with Scott MacDonald2

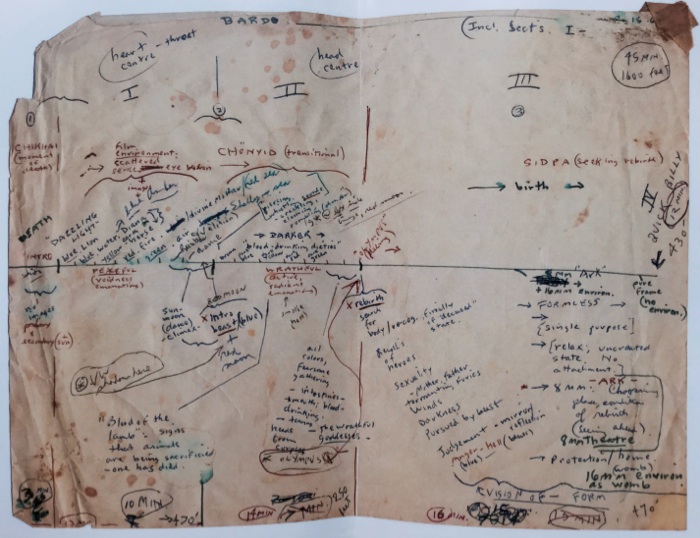

Baillie’s notes for Quick Billy, from the booklet accompanying the DVD of the film (photo courtesy of R. Bruce Elder).