For Love and Honor

Box 99

Eaton New York 13334

January 7, 1973

Mr Donald Richie

Curator of Film

The Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53 Street

New York, New York 10019

Dear Donald:

I have your letter of December 13, 1972, in which you offer me the honor of a complete retrospective during this coming March. Let me stipulate at the outset that I am agreed “in principle”, and more: that I appreciate very deeply being included in the company you mention. I am touched to notice that the dates you propose fall squarely across my thirty-seventh birthday. And I am flattered by your proposal to write notes.

But, having said this much, I must go on to point out some difficulties to you.

To begin with, let me put it to you squarely that anyone, institution or individual, is free at any time to arrange a complete retrospective of my work; and that is not something that requires my consent, or even my prior knowledge. You must know, as well as I do, that all my work is distributed through the Film-Makers’ Cooperative, and that it is available for rental by any party willing to assume, in good faith, ordinary responsibility for the prints, together with the price of hiring them.

So that something other than a wish to show my work must be at issue in your writing to me. And you open your second paragraph with a concise guide to what that ‘something’ is, when you say: “It is all for love and honor and no money is included at all…”.

All right. Let’s start with love, where we all started. I have devoted, at the nominal least, a decade of the only life I may reasonably expect to have, to making films. I have given to this work the best energy of my consciousness. In order to continue in it, I have accepted… as most artists accept (and with the same gladness)…a standard of living that most other American working people hold in automatic contempt: that is, I have committed my entire worldly resources, whatever they may amount to, to my art.

Of course, those resources are not unlimited. But the irreducible point is that I have made the work, have commissioned it of myself, under no obligation of any sort to please anyone, adhering to my ow best understanding of the classic canons of my art. Does that not demonstrate love? And if it does not, then how much more am I obliged to do? And who (among the living) is to exact that of me?

Now, about honor: I have said that I am mindful, and appreciative, of the honor to myself. But what about the honor of my art? I venture to suggest that a time may come when the whole history of art will become no more than a footnote to the history of film…or of whatever evolves from film. Already, in less than a century, film has produced great monuments of passionate intelligence. If we say that we honor such a nascent tradition, then we affirm our wish that it will continue.

But it cannot continue on love and honor alone. And this brings me to your: “…no money is included at all…”.

I’ll put it to you as a problem in fairness. I have made let us say, so and so many films. That means that so and so many thousands of feet of rawstock have been expended, for which I paid the manufacturer. The processing lab was paid, by me, to develop the stuff, after it was exposed in a camera for which I paid. The lens grinders got paid. Then I edited the footage, on rewinds and a splicer for which I paid, incorporating leader and glue for which I also paid. The printing lab and the track lab were paid for their materials and services. You yourself, however meagerly, are being paid for trying to persuade me to show my work, to a paying public, for “love and honor”. If it comes off, the projectionist will get paid. The guard at the door will be paid. Somebody or other paid for the paper on which your letter to me was written, and for the postage to forward it.

That means that I, in my singular person, by making this work, have already generated wealth for scores of people. Multiply that by as many other working artists as you can think of. Ask yourself whether my lab, for instance, would print my work for “love and honor”: if I asked them and they took my question seriously, I should expect to have it explained to me, ever so gently, that human beings expect compensation for their work. The reason is simply that it enables them to continue doing what they do.

But it seems that, while all these others are to be paid for their part in a show that could not have taken place without me, nonetheless, I, the artist, am not to be paid.

And in fact it seems that there is no way to pay an artist for his work as an artist. I have taught, lectured, written, worked as a technician…and for all those collateral activities, I have been paid, I have been compensated for my work. But as an artist I have been paid only on the rarest of occasions.

I will offer you further information in the matter:

Item: that we filmmakers are a little in ouch with one another, or that there is a “grapevine”, at least, such as did not obtain two and three decades ago, when The Museum of Modern art (a different crew then, of course) divided filmmakers against themselves, and got not only screenings, but “rights” of one kind and another, for nothing, from the generation of Maya Deren.

Well Maya Deren, for one, died young, in circumstances of genuine need. I leave it to your surmise whether her life might have been prolonged by a few bucks. A little money certainly would have helped with her work: I still recall with sadness the little posters, begging for money to help her finish The Very Eye of Night, that were stuck around when I was first in New York. If I can help it, that won’t happen to me, not to any other artist I know.

And I know that Stan Brakhage (his correspondence with Willard Van Dyke is public record) and Shirley Clark did not go uncompensated for the use of their work by the Musuem. I don’t know about Bruce Bailey, but I doubt, at the mildest, that he is wealthy enough to have travelled from the West Coast under his own steam, for any amount of love and honor (and nothing else). And, of course, if any of these three received any money at all (it is money that enables us to go on working, I repeat) then they received an infinite amount more than you are offering me. That puts us beyond the pale, even, of qualitative argument. It is simply an unimaginable cut in pay.

Item: that I do not live in New York City. Nor is it, strictly speaking, “convenient” for me to be there during the period you name. I’ll be teaching in Buffalo every Thursday and Friday this coming Spring semester, so that I could hope to be at the Museum for a Saturday program. Are you suggesting that I drive down? The distance is well over four hundred miles, and March weather upstate is uncertain. Shall I fly, at my own expense, to face an audience that I know, from personal experience, to be, at best, largely unengaging, and at worst grossly provincial and rude?

Item: it is my understanding that filmmakers invited to appear on your “Cinieprobe” programs currently receive an honorarium. How is it, then, that I am not accorded the same courtesy?

Very well. Having been prolix, I will now attempt succinctness. I offer you the following points for discussion:

1] It is my understanding, of old, that the Museum of Modern Art does not, as a matter of policy, pay rentals for films. I am richly aware that, if the museum paid us independent film artists, then is would be obliged also to pay rentals to the Hollywood studios. Since we all live in a fee-enterprise system, the Museum thus saves artists from the ethical error of engaging in unfair economic competition with the likes of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. (I invite anyone to examine, humanely, the logic of such a notion.) Nevertheless, I offer you the opportunity to pay me, at the rate of one-half my listed catalog rentals, for the several screenings you will probably subject my prints to. You can call the money anything you like: a grant, a charitable git, a bribe, or dividends on my common stock in Western Civilization…and I will humbly accept it. The precise amount in question is $266,88, plus $54,- in cleaning charges, which I will owe the Film-Makers’ Cooperative for their services when my prints are returned.

2] If I am to appear during the period you propose, then I must have roundtrip air fare, and ground transportation expenses, between Buffalo and Manhattan. I will undertake to cover whatever other expenses there may be. I think that amounts to about $90,-, subject to verification.

3] If I appear to discuss my work, I must have the same honorarium you would offer anyone doing a “Cineprobe. Correct me if I’m wrong, but I think that comes to $150,-.

4] Finally, I must request your earliest possible reply. I have only a limited number of prints available, some of which may already be committed for rentals screenings during the period you specify. Since I am committed in principle to this retrospective, delay might mean my having to purchase new prints specifically for the occasion; and I am determined to minimize, if possible, drains on funds that I need for making new work.

Please note carefully, Donald, that what I have written above is a list of requests. I do not speak of demands which may only be made of those who are forced to negotiate.

But you must understand also that these requests are not open to bargaining: to bargain is to be humiliated. To bargain in this, of all matters, is to accept humiliation on behalf of others whose needs and uncertainties are greater even than mine.

You, of course, are not forced to negotiate. You are free. And since I am too, this question is open to discussion in matters of procedure, if not of substance.

I hope we can come to some agreement, and soon. I hope so out of love for my embattled art, and because I honor all those who pursue it. But if we cannot, then I must say, regretfully, however much I want it to take place, that there can be no retrospective showing of my work at the Museum of Modern Art.

Benedictions,

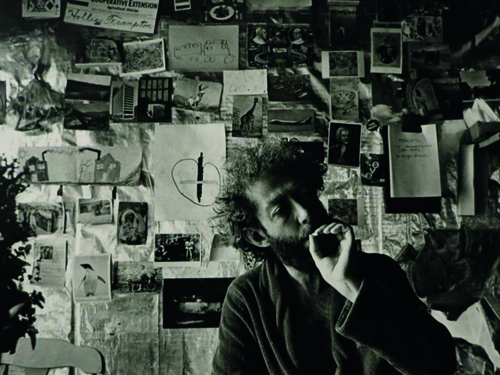

Hollis Frampton

With thanks to Will Faller and the Hollis Frampton Estate