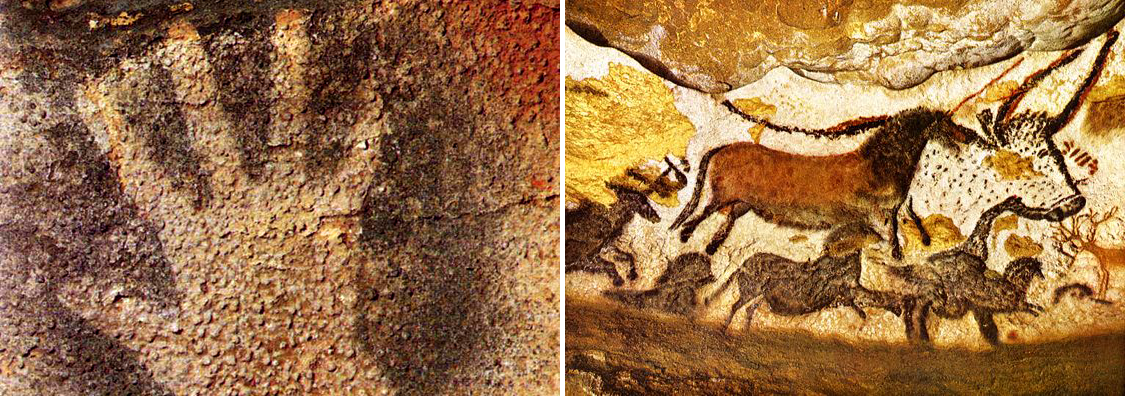

The Negative Hands

Caves appeal to the imagination. It is here that signs of early human history have been preserved. In these prototypes of rooms, Paleolithic people found protection. In contrast to the temporary shelters of wood and clay, these places were emblems of durability. They were occupied from generation to generation, and the objects found there still bear witness to the way of life of these cave dwellers. But the most astounding discoveries were made deep inside the corridors where the first paintings in the history of the world were found. The cave can be seen as the womb of human culture.

But Plato put the idea of caves in a different light forever. In his allegory, he presented the cave as the stage of false knowledge. The immaterial light of truth radiates outside of the cave, while the foolish human lets himself be charmed deep into the hollows by a shadow play. The real objects remain behind his back, but the shadows they cast present themselves as reality.

As paupers of knowledge, we are thus condemned to a life in darkness. But maybe we should embrace our fault and penetrate the cave even further in order to really understand what takes place outside of it. These shadows contain a truth that may only become visible in a dim glow.

In the caves of Lascaux in France, animals are depicted. Sometimes they stand alone, but often the figures overlap. They supervene and cover each other. The animals seem to be moving; their legs are raised. And when viewed by the light of a torch, they seem to be moving. The texture of the rock wall makes the light cast fickle shadows and new silhouettes emerge one by one, every time a trifle different from the previous one. The one walking through this cave sees animals in motion, brought to life by their own movement. The shadow play makes one think of cinema, in which the same game of illusion of movement is being played. In the dancing light, matter comes to life.

Soon enough, it seems strange to the spectator how the paintings overlap. A plan seems to be lacking. Moreover, the older paintings are not considered in the newer compositions, as if they didn’t matter at all. The crisscross of shapes reminds of the tags sprayed on city walls, not the solicitous depiction of sacred images. The only way this could be explained is that the result was not the purpose of the paintings. The French philosopher Georges Bataille dedicated an important part of his writings to the caves of Lascaux. He claims the paintings were not meant as a decoration, nor served a religious function. The painting had no purpose in the future, so that, at the moment of creation, there was no other reality than the act of painting. One was not focused on any functionality, but one was absorbed by the moment in which forms emerged from the movements of the hand of the painter. Or as the writer Francis Ponge parses the French word for ‘now’ as ‘taking in one’s hand’: main-tenant. ‘Main’ means hand and ‘tenant’ means taking.

Marguerite Duras based her film Les mains négatives on the Magdalenian caves at the Atlantic coast, where the imprints of hands were found. Thirty-thousand years ago, someone placed her1 hand against the cave wall and sprayed pigment over it, creating a coloured halo of the hand. When she did this, her hand transformed from a tool into an image. The moment the painter made these imprints is fossilized. Even though the moment of this act took place thousands of years ago, it still exists.

The film of Duras comprises of only a few shots. The camera films through the window of a car as it drives through Paris. The light is intensely blue. Slowly, the sun dissolves the colour and brings the city to life. A voice sounds, describing the negative hands as a petrified cry. The hands express enthrallment, the awareness of the endlessness of the sea and the inviolability of the European woods that extend relentlessly around her. A small human body that is naked in relation to the immensity of things. And a human that, maybe for the first time, feels a love to be part of this universe. The negative hands on the wall are an outcry: “I love!”.

That scream lasted for thirty-thousand years in absolute solitude. She was alone; all hands are the same size. Now, many millennia later, we are together with her because the imprints she made allow us to follow her movements. When we look at the handprints, we see how she must have stood there in that cave. The delicate colours she used, the grit she spread her hand upon: what she saw is still visible. Thanks to this petrified moment, the distance in time between the maker and the observer can be cancelled out. When we see the intimate traces she left behind, the gesture of making and the contact of looking meet one another. This is why making art or film is touching. The moment of creation can happen in absolute loneliness, but at the moment the viewer sees the work, he or she is capable to shatter time and space to be together with the creator. The thoughts and gestures of the creator are shimmering in the now. The painter of the negative hands is no longer alone in that place, even though it took thirty-thousand years until her lonely gaze became a collective one.

Les mains négatives is, just like the negative hands, a fossil of time. The image of the city glides past the camera, as nonchalant as time itself. With the words “thirty-thousand years ago”, the reality of the city suddenly becomes brittle. The hands are still present on the granite, but will the city still exist in thirty-thousand years? When you look at the film today, you can see how much the world has changed. The images show what Paris looked like in 1978. A city that no longer exists. The streets through which the camera passes look different nowadays. Other people live there now. The cars have new shapes. Even the light reflects in a different way. The film shows a distant world, an illusive reality.

One can be mournful about the unreal character of these shadow images. But the only way of sharing a world with people who look from different places or another time is by making a representation of reality. The weak light from the projector leads us away from reality and makes us quiver because of things that are not real but true. The space of cinema, which is continuously being redrawn, emerges on the empty surface of the white screen. The negative forms of hands, faces and houses emerge – and supersede one another. A scream fades, but it can endlessly resound in the ears of the now.

- 1Even though Marguerite Duras speaks about ‘he’ and ‘him’, the artists were presumably female. Virginia Hugues, “Were the First Artists Mostly Women?”, National Geographic, October 2013.

Images (1) and (2) are rock wall paintings from the caves of Lascaux

Image (3) from Les mains négatives (Marguerite Duras, 1978)