Straschek 1963-74, West Berlin

Part 3

The title of the text “Straschek 1963–74 West Berlin” is as simple as it is informative: it is a subjective, self-reflective insight into Günter Peter Straschek’s eleven years in West Berlin. During this time, he was many things: filmmaker, film historian, film theorist, writer, politically active in the protest movement of 1968 and part of the first generation of students at the Deutsche Film- und Fernsehakademie Berlin [German Film and Television Academy Berlin] (DFFB). Straschek’s fellow students included people like Helke Sander, Harun Farocki, Hartmut Bitomsky, Johannes Beringer and Holger Meins. His essay provides unique access to the film-aesthetic and -theoretical debates and practical-political discussions of a generation of filmmakers who were to fundamentally renew filmmaking in Germany, and whose political and formal experiments made the preceding generation of Oberhausen Manifesto filmmakers look staid. Born in Graz on 23 July 1942, Straschek merged his experiences and interests from his West Berlin period into one condensed virtuoso composition for the magazine Filmkritik. Straschek created a constellation of various text types, such as political-theoretical and film-aesthetic reflections, anecdotes, diary-like entries, letters or even feeding instructions for Danièle Huillet’s cat. It is a text montage that most filmmagazine editors today would probably shorten considerably and change formally. The text owes its publication in this form to the spirit of the time, but especially to the editorial guidelines of Filmkritik, which was certainly the most prominent film magazine in the German-speaking world at the time.

– Julian Volz1

44.

After being definitively expelled from the DFFB, I went to Frankfurt in 1968–69 to organize the secondary school student film project. It was based on ideas, worked out mainly by myself together with Holger M., about film work aimed at target groups. Target-group film work came into fashion and found incompetent imitators; since then, it has become one of the many attempts to do socialist film work that have not led to significant progress. Although it proved impossible to complete the project, many of our partial results were successful and still matter; and, overall, I still have pleasant memories of those days in Frankfurt. Sorry: it was the last phase of comradely existence marked by a readiness to communicate and the absence of partisan tendencies. Groups of students received 8mm equipment and technical training from us (Holger M., who had yet to be expelled, was the contact person with the DFFB). They were supposed to film individual subjects that they were interested in and integrate them into agitational work in the schools. Down to the editing stage, they worked quite enthusiastically; after that, interest waned. (This was fostered by the “art is shit” politics of certain groups close to the Marxist-Leninists. These were the days in which “Put theoreticians in concentration camp!” was smeared on the walls of the rooms of certain veteran comrades in Frankfurt.) Although the students weren’t aware of it at the time, the filmed material was sometimes magnificent and, on average, quite successful. What is more, the concept behind filmmaking helped show that problems had to be observed more concretely: terms such as “society,” the “repressive family home,” “pressure to succeed” were easy to use in arguments or on fliers, but how could one “shoot” them without losing the abstract contents? At first, we let ourselves be guided by the leaders of the secondary school student movement of the day; later, however, we abandoned them, because they were more concerned about their future political careers at university than about the interests of their fellow students. We turned toward the grass roots, as the phrase goes, the considerably less politicized students. We were aware of the shortcomings in our undertaking; we were supposed to carry the project out with apprentices, but I didn’t consider myself in a position to do that because of my lack of experience. On the basis of a reciprocal agreement, I tried to defend the interests of secondary school students with a teachers’ association calling itself the SLB [Sozialistischer Lehrerbund/Socialist Teachers’ Association], but seem to have built up no little aversion for “leftist” teachers in the process. In retrospect: the student film project was an experiment that produced experiences and interim results which we should have expanded by pursuing them further. Thanks are due to the participants and, in friendship, to Luy T. and, especially, Edith S. and David H. W., for being always ready.

45.

A decadence-artist from the composer clan who is constantly bustling about in the cinema subculture opined that I am terribly self-centered – although she of course is too, but, precisely, “less successfully.” It is likewise often said that I imagine that only what I say is right. I do indeed ascribe a decidedly subjective correctness to my opinion, and I expect and demand the same thing of my interlocutors, so that we can come closer to establishing criteria of validity through communication (not just verbal communication, of course), or, again, can put opinions and theses constantly to the test. And I am arrogant, aggressive, and hurtful, the standard criticism goes. I have, however, never in my life behaved aggressively toward the class whose objective exploitation allows me to pursue such a privileged existence; I’m arrogant only toward my peers, and my arrogance is “better” than that of the countless mediocre (and, latterly, left-opportunist) intellectuals in my sector – and more honest to boot. I am polite and give my seat to immigrant women workers in the subway; on the other hand, I call Rainer Werner F. a “lousy pig of an exploiter.”

46.

On the Concept of “Critical Communism” in Antonio Labriola (1843–1904) was produced “independently” for 7,500 marks; that is, JeanMarie S. and Johannes B. contributed a couple thousand marks and Dr. Alexander K. or, rather, the Ulm Institute for Film Design paid for materials as well as rental fees. Naturally, the Kuratorium [foundation for contemporary German cinema] didn’t give us a cent, and the film didn’t qualify for the Mannheim Film Festival and wasn’t bought by a television station; it wasn’t possible to pay the crew, and the actors could only be invited to a dinner at a restaurant. On top of everything else, I had to go through the song-and-dance about “worker participation” and the like so that I could at least approximately realize my ideas about how to produce the movie. Like all my short films, this one too was about socialism and/or women, and, as always, women’s and leftists’ reactions to it bordered on outrage. It is, moreover, odd how touchy people get when it is a question of their own problems: a group of people sharing an apartment wouldn’t let me shoot in their big common room because, when asked who the movie was for, I said “for us” (instead of saying mine workers or housewives: that was in fashion in a big way back then, though I doubt that a film for a target group has ever reached its target, much less influenced it). During the shooting, I suddenly had the feeling that it was unspeakably stupid of me to play at being a director under such conditions. I haven’t made a single film since then; more precisely, I’m no longer willing to shoot a film under similarly “independent” conditions, with money scraped up here and there. This has to do with my conception of work and cinema. A partisan of studios opposed to all improvisation and spontaneity, which are in my view synonyms for sloppiness, I’m for artistic-synthetic films, in line with BB’s “there really is ‘something to be constructed,’ something ‘artificial,’ something ‘posed.’” And this conception of mine about the (re)production of social reality for the movie screen costs money, more money than the usual con game about “filming the real world” does. Naturally, I don’t have access to such money yet.

The months I spent making the Labriola film were, nevertheless, almost a pleasure, with the thoroughly enjoyable feeling that comes from tinkering around for a long time with a screenplay (along with colleagues). In rather high spirits and inclined to dramatize things, cherishing high hopes, I for the first time consciously experienced this atmosphere of adventure, that is to say, this prolongation of my youth, as cinema. I fell in love for all eternity with an actress, affording myself the luxury of Love with a capital L – “ill-starred,” of course.

47.

I’ve never concerned myself with structuralism. I have no time and no inclination at all to go chasing after every new bourgeois academic vogue, in amateurish fashion at that. Five years from now, I’ll inquire into the current state of the knowledge this method has produced. So far, it doesn’t seem that I’ve missed much as a result of my indifference.

48.

After the Labriola movie came the last phase of work on Handbook against Cinema. For the actual composition of the book, eight hours a day at the typewriter followed by revision, I retreated to Wedding. With the filmmaker Helmut R., who worked in Japan as a newspaper correspondent, I occupied a two-room apartment without amenities. Materially, we were in a very bad way. I wouldn’t and couldn’t do anything else if I wanted to finish Handbook against Cinema as soon as possible.

Harun F., with Hartmut B.’s collaboration, lent me – heartfelt thanks! – the monthly rent of 250 marks for the toughest period, and Johannes B., Hanspeter K., and Dr. Klaus K. (because he didn’t have the “correct line” yet) also showed their solidarity – unlike, for example, Prof. Dr. Friedrich K., who refused to lend me 500 marks. I was nevertheless forced, in late 1970early 1971, to take college teaching jobs in Braunschweig and Hamburg. I was finally able to finish Handbook against Cinema late in the summer, in the storage room of a shared West Berlin apartment crawling with empty-headed actor types. This was preceded, in July 1971, by serious breakdowns.

[Why I wrote the little antifilm history book by myself rather than as part of a “collective.” For starters, there aren’t as many filmmakers and historians of the movies as there are Germanists, sociologists, and so on. Second, I had a particular conception of cinema to defend, one geared to my understanding of politics. What’s more, the handful of people who understand and can write something about film in this country, Hartmut B. in West Berlin, Helmut F. in Munich, or, indirectly, David H. W. in Frankfurt, are no less “difficult” than I am – pretty touchy, in fact. And, not least, I wanted to savor the adventure of a first publication: the process of gradually approaching a desired result and, even more, that of finetuning different versions and passages and trying to find a terminology adequate to the problem under consideration. The work I had to do to pay for the groceries pushed completion of the book back by a year and more. Admittedly, I had miscalculated the time required to produce the critical apparatus.

(Hartmut B. had likewise been working on his first book publication. We both noted that we’d lost our naïveté and, grinning, agreed that we’d indeed learned something of the craft: how to bluster through weak spots in the argument with “complicated language”; which secondary-literature constraints have to be respected; where one can bluff and set traps; how a study several hundred pages long ought to be composed; the fact that there are too few ways of beginning a sentence, and so on and so forth.)]

49.

Cynicism. If I were a factory worker and one of those film academy students came to see me on the shop floor, pointing his camera at my assembly line to capture my exploitation on celluloid, and if this scholarship student then tried to get chummy with us in the canteen during lunch break, jabbering something incomprehensible about liberating the proletariat as he clapped us on the shoulder, and if he proceeded to show his political film at a film festival before finally selling the product off to TV, I would have to exhibit considerable reserve …

50.

Under the Weimar Republic, reciprocal disparagement became a recognized art form. As is well known, it attained, in certain cases – Kraus, Kerr – the level of the neurotic classic. West Germany embodies the opposite extreme. Individuals, as interchangeable representatives of an association, have become inviolable: this is hypocritically palmed off as morality. What is in fact a lame, passionless, unaggressive attitude to opinions and things is held in high esteem as “objective” debate. The intention not to “hurt” one’s opposite number is, to be sure, due less to respect for this person than to uneasiness about losing advantages. In the world of TV, for example, no one is anyone’s personal enemy: although nobody likes anybody, the reigning professional ethic mandates eschewing “personal” debates, and this, in turn, serves to impede objective ones. In such a configuration, the intelligence, wit, and aggressiveness of a Fritz Körtner can only be experienced as liberating. Indeed, I consider the strict separation of objective and personal debate to be, generally speaking, wrongheaded and impracticable. Causes always come with people attached to them; and, where a cause is at stake, people should also be named.

Just one example: for years, a journalist by the name of Peter B. Sch. has been passing himself off as a “specialist” in Latin American cinema. The fact of the matter is that the individual in question doesn’t know three words of Spanish or Portuguese even today. Instead, he has cribbed every important piece of information from a genuine expert, namely, Franco M.; in general, he has filched everything he’s written from others, swindled colleagues, and the like. What this has yielded is irresponsible, sensationally dramatized reporting about “revolutionary” Latin American cinema. In the meantime, people have taken a sober distance from all this, and Latin American cinema, although its prestige has declined and it garners less attention than before, has hardly become the worse for that. The initial situation, however, in which the term “revolutionary” was mistakenly attached to all aspirations for greater freedom and everything modern (a modernism often wholly in the interests of national, anti-North American capital) – and this in the movie business, no less – was a sign of ignorance and opportunism in journalism or pseudo-journalism. Our Peter B. Sch. has drawn the consequences from the declining vogue for “his” Latin American cinema: he has now turned to pre1933 German proletarian cinema. With that, he has at least eliminated the biggest linguistic problems.

51.

I’ve never enjoyed teaching or gained anything from it, least of all in a state college of fine arts, those state-run breeding grounds for irrationality, where teachers and students are out to do each other one better at cooking up pretentious ideas. In the Hamburg State College of Fine Arts, I replaced Werner N. as the cinema class teacher for four months; I even had to take part in the entrance exam farce (my advocacy of numerus clauses instead of the prevailing talent-based entrance criteria was mistaken for cynicism) and constantly attend meetings – for a monthly salary of about 1,250 marks net.

[The best job conditions I’ve had so far were at the University of Television and Film Munich, where I ran a seven-day seminar on “Pre1920 Cinema” which may have been of some interest to the extent that it provided a reasonably good overview of film’s modernity (and aggressiveness) before its forcible transformation into art. Remuneration: 2,100 marks + travel expenses. A four-day seminar on the “American B-Picture” – remuneration: 1,800 marks + travel expenses. (If one wishes to prepare a seminar properly, the aforementioned sums are by no means as impressive as they might seem at first glance to someone on a salary.) Student indifference, promoted by state policies à la Bavaria [the name also references a Munich-based film production company] that have deintellectualized higher education, convinced me not to pursue similar opportunities to earn money.]

My highly personal and differentiated relationship to cities: I’m in love with Amsterdam, go into raptures about Rome (though I couldn’t live there long), don’t like Paris, found Ankara unpleasant and Jerusalem fascinating. Rarely has a place seemed as repellent to me from the very first as Braunschweig did. What’s more, whether it was the name Braunschweig, Braunschweig’s postal code, 33, or the naturalization of senior civil servant Hitler, the rightwing conservative mindset combined with the (latter-day) borderland mentality reminded me of Graz. A resplendent picture of Chiang Kai-shek hung high in a Chinese restaurant; I left the establishment (the way I’ve left waiting rooms when a doctor with dueling scars walked in). The Braunschweig State College of Fine Arts paid me 342 marks a month for a job calling for four hours of teaching per week, and I had to cover my own travel expenses and board and lodging myself (I wasn’t even provided with a place to sleep in the college). I accepted the job nevertheless, because there was a chance that Hartmut B. and Harun F. could take similar posts teaching cinema classes in other cities, meaning that the three of us would have been able, in the long term, to organize a work program.

Two developments were to cause me problems: the fact that movies had become a horribly fashionable trend, and the Marxist-Leninists’ pseudo-radicalism, which had by now spread to the provinces. In both Braunschweig and Hamburg (at the time, thanks to such formidable representatives of philosophy as Max Bense and Bazon B., Hamburg had inscribed “the scientific approach” on its banners: if an art school student asked three housewives about a subject he wanted to paint, that not only established “the social context,” but simultaneously proved that work had been done in “statistics”), the movie-vogue was a hindrance to the extent that painting or drawing had suddenly become “reactionary”; everyone wanted to shoot films or take pictures, work in mass communication, and so on. For example, a student who was in something like his tenth semester of painting came to see me and declared that he was abandoning painting because one couldn’t change society with it; that’s why he wanted to take my cinema class. After mulling the matter over for a long time, I decided to close admissions to the class, not so that I could train a small circle of experts, something that the technical equipment at our disposal would in any case have ruled out, but so that the college wouldn’t produce, on the basis of a temporary political fashion, a small army of poorly trained filmmakers with no chance of success who would, at all events, end up being art teachers. Engaging students at the college in halfway reasonable discussions became a nightmarish strain. Deliberately cultivated chaotic thinking, an extreme lack of discipline, ignorance of politics and simple facts, a perpetual obsession with showing off one’s unique individuality – all this became, thanks to the students’ partial awareness of the dismal careers awaiting them, either lachrymose or hysterical. Most fine arts students fared the way many women do: a halfhearted politicization (or emancipation) that doesn’t get as far as radicalization and isn’t bound up with work does more harm than it helps to solve problems, because it merely destroys an existing, unconscious intact condition, whereas the ensuing fragilization doesn’t, at least at first, make any fundamental change possible. The consequence is often pain + in time, a relapse.

When I was with the “Maoists,” I suffered when it came to what I expected of comrades. There weren’t many of them in Braunschweig or, more importantly, Hamburg; they had a reputation for being the most political among us and were very important in a certain phase of the anti-teacher struggle. Yet they are (like the Maoists in West Berlin as well) classic examples of precisely that which, of all things, they don’t want to be, namely, artists – politics as a continuation of art by other means. Their irrationality finds expression in the “consciousness” that one can get the better of pending problems by mechanically reciting dogmas (about the proletariat, by Marx and Mao). Their aesthetics found its culmination in the suggestion that we film their May Day march. I asked, by way of objection, what good that would possibly do, given that we would in the best of cases only be able to watch ourselves, but this, I was told, was just a reflection of my “attitude,” which was “hostile to the masses.” In certain cases, it must be said, highly neurotic modes of behavior were unmistakable. At the fine arts colleges in Braunschweig and Hamburg as everywhere else, the Marxist-Leninists were characterized by fantastic ignorance, distinct pride in their lack of (“bourgeois”) knowledge, and the fear (so typical of party officials) of producing anything at all – because anything they produced would fall short of their verbally radical pretensions. This discrepancy took on increasingly pronounced forms. Thus I tried to argue as follows time and time again: because Marx and Mao are right, we have to try to change society at the side of the proletariat and the oppressed, and in their interests (not “as” proletarians – that was most likely my “mistake”); in the case before us, in our own profession. Thus if they meant to become socialist filmmakers (and if they didn’t, it behooved them to get lost in order to make room for others), they should seize the opportunity to learn, learn, and learn some more at the state-supported college of fine arts: by watching and analyzing movies, gaining an understanding of the theory and history of cinema, planning group projects down to the last detail, practicing coordination and, above all, learning the craft. And coming to understand, finally, something about the economy of the motion picture industry. But it was all in vain. My reasoning had once again unmasked me, not just as a revisionist, but as a class enemy, no less.

[Premise: the protective bubble of a state college of fine arts. If these “Maoists” had ever experienced even a trace of what they pretended to be fanning the flames of, class struggle, I would scarcely have come to the bitter conclusion that the workers and, above all, proletarian youth had to be protected from such parasites.]

After six months of this silliness, in May 1971, I’d had my fill. My pay had gone up to 412.60 marks a month. I threw in the towel, with, most assuredly, myself and my own interests in mind. Since then, I avoid state colleges of fine arts and have no information about the current state of cinema classes. Someone or the other informed me that Gerhard B. from Dörnberg, near Kassel, has succeeded me in Braunschweig. That’s where he belongs.

52.

Me: “At least you’re doing better in Rome than you were in Munich: you can even afford a cat (Misti). And you’ve also succeeded, despite the most severe sort of problems, in carrying out all your projects. Every one of your new films meets with worldwide interest; the first monograph has appeared in English. In the history of cinema, one can hardly find another case of someone winning recognition and international fame in a few years with just a couple of films, the way you already have.” Jean-Marie S.: “But you know better than I do that nothing like the history of cinema exists.”

53.

The Left likes to go to the movies, without admitting it. Lots of lovely sentimentality and adventure, for which one would unfortunately have to be ashamed outside the protective darkness of the movie theater. But the sentimentality and adventure have to present themselves as reality; they can’t be exposed as artifice. The dream factory is scorned for being a place where dreams, not flat naturalism, are manufactured. If, in a “fascistic” cops-and-robbers flick, the bad white guy tells a good black guy at gunpoint that he’s prepared to rip his ass open all the way to his balls (that, at least, is what he says in the dubbed West German version), our moviegoer is happy – as long as Ava Gardner’s perfect makeup in the middle of the jungle doesn’t expose the film to courageous criticism (a hairdresser in the middle of a tropical forest ain’t no reality). First it took the intellectuals nearly two decades to get up the courage to laugh over Jerry Lewis; now they’re amused by every trash film in sight, even if it’s as pitifully “anti-intellectual” as a Woody Allen. It is truly amazing to see how helpless highly intelligent and rhetorically skilled leftist intellectuals become in front of a screen, when they ought to be piecing together artificially produced images (of reality), and to see how aggressively they react when those images don’t immediately evoke the real world. An inexplicable reluctance to think and a lamentable “disinclination to be creative” crop up precisely where complex procedures for reflecting complex realities ought to be discerned. Leftwing students have never been discriminating in movie theaters: they want to see pictures “like Kuhle Wampe” (as if such movies were legion); in a pinch, an obscenity such as Themroc will do. A few digs at the rich and the cops plus a dash of liberation ideology in the guise of a fuck plus a couple of red flags – that seems to be enough for late shows before and after an evening in the pub. To repeat: what transpires on the screen isn’t the real as such, although some parts of it do present themselves as filmed reality. Not whether a cinematographic work is realistic, but how it is remains the question.

A maxim to keep in mind: it isn’t possible to produce good movies, novels, etc. for fascism; it most assuredly is possible to produce bad works of art for the socialist movement.

54.

The effort to arrive at a “dialectical relationship” between continuity and change and also between general knowledge and specialized knowledge is a crucial part of my being. Here, too, following the traces would lead back to my childhood. With the pleasure my work gave me, organizing it became an additional pleasure; I am neither journalist, scholar, nor artist, I am a publicist. I endeavor, accordingly, to produce a sequence, both necessary and pleasurable, of various themes (change, specialized knowledge) from a fixed set of the subjects that interest me (continuity, general knowledge). I shall not only attempt to produce the most satisfactory version of these relations that I can in my private life, but also, of course, to subordinate them to political imperatives and requirements. This is, for me, an altogether paradoxical ideal (which finds expression in Eisler): to deliver something, a commission (the working class).

Too smart for cinema and too dumb for scholarship, so to speak. I’m still in love with television and the movies. But I simply haven’t been able to take the business altogether seriously for a while now.

55.

By spring 1972, I’d had enough of the years of shared apartments. To rent a one-room apartment, however, I had to put down a security deposit. My running projects and work-in-progress weren’t generating any income yet. So I turned to the Hessischer Rundfunk, proposing to do a program for Titel, Thesen, Temperamente about professional reeducation (of West Berliners with diplomas in political science). My proposal was accepted. Three weeks of research – this was to be my first TV production. Even before shooting got under way, I had a row with the cameraman: I banned all zooming around and demanded a tripod. He had the steadiest hand at the station, was the reply; I wouldn’t notice a thing. It was all I could do to convince him to forget about closeups under glaring spotlights (if only because of the inadequate equipment) and settle for room shots with floodlights (for TV cameramen, anything that isn’t an extreme closeup is a long shot). When I demanded tracks for a camera movement around a table, the result was immediate consternation. People acted as if the TV station couldn’t invest another two hundred marks, although when it comes to godawful entertainment shows, they spend money like there was no tomorrow. Savings are to be made on regular magazine-format programs, on everyday TV fare alone; only in that department is the watchword gray mediocrity and a lackluster going-through-the-motions. The assigned editor in Frankfurt, Dr. Swantje E. (whose relationship to cinema was like W. C. Fields’s to dogs and little children), was as deeply insulted by my attitude as my German teacher had been fifteen years earlier when, instead of a report on Grillparzer, I passed in one on hula hoops. For the custom is for the poor film editor to cut the material down to twelve minutes somehow or other while Mr. Filmmaker seated next to her dashes off his commentary in no time flat. I had – simply because this kind of filmmaking and news broadcasting horrifies me, because I can’t stand these meaningless images accompanied by a hastily rattled off commentary – so conceived my contribution as to make commentary superfluous; the protagonists’ different views (sequences of takes), in counterpoint, as it were, had only to be pasted together. (The film editor considered this to be detrimental to her profession.) A static sequence of mine that ran for seven minutes brought on the coup de grâce. It mustn’t be supposed that the TV editor paid any attention to what was important about what was said in those seven minutes: after less than a minute, she asked me, troubled by the untroubled image, whether things were going to go on this way. I politely replied that they were. She ordered the editor to fast forward the sequence. After that, of course, I was treated to the ancient spiel about the millions of TV spectators and our responsibilities – as if the TV crowd had ever had any concern for the audience. I countered that the audience wasn’t as dumb as television people (tacitly, of course) arrogantly assumed (and frankly intimated in insulting, feebleminded “introductions” to feature films), and that it most assuredly would prefer a piece of calm, incisive documentary reporting to these pseudo-objective magazine programs edited slapdash, à la Titel, Thesen, Temperamente. At any event, Dr. Swantje demanded that the whole thing be done “again and better.” I had no choice but to refuse, if only because I can’t do any “better.” A couple weeks later, I received notice of payment (of a cancellation fee): I was to be paid 328 marks! Two years later, the television editor Werner D. was looking for coproducers for the series on emigration in the movie industry. The Hessischer Rundfunk turned him down. I must have done something awful there, was his impression.

56.

Mother was given a hard time of it bringing me up; Father made it easy for himself. Yet I have him to thank for things of crucial importance: hatred of fascism and contempt for religion/the irrational/ the Church, a passion for dirt-track racing (as a child) and soccer (to the present day), knowledge of socialism and sympathy for it. Hero worship and sorrow when it came to Martin Schneeweiß (who succumbed to the serious injuries that he had suffered when, with his rival Gunzenhauser, he took a fall in the northern curve of the trotting course) and also Koloman Wallisch and Karl Münichreiter, both of whom were summarily hanged by the Austrian fascists in February 1934. Every Sunday, I went with Father to a soccer match at the Sturmplatz. (This was the first “class struggle” in my class at school. The “better sorts” rooted for the GAK, “ordinary folk” and the Reds for Sturm Graz.) My questions and his answers were my first lessons in politics. I didn’t understand my father’s fierce anger over Nazism, which meant national socialism, didn’t it? One day a Jehovah’s witness yelled “God is coming!” in our direction; my father asked, irritated: “How do you know? Did he write you a postcard?” I was extraordinarily impressed by this answer: it sowed the seeds of my anti-metaphysical attitude.

In my fourth year at the Bundesrealgymnasium, my atheistic grousing started to worry my parents. During religious instruction, I tried my hand at all the hairsplitting subtleties in the God-can’t-possibly-exist line. [I had been baptized at the age of three, incidentally: the arch-Catholic and also arch-anti-Nazi peasants with whom Mother and I had been relocated during the war asked her for permission to have me christened, to pay a debt of thanks, so to speak. For the Red Army was on the march, and, if something happened to me, I wouldn’t go to heaven. My parents consented, “for the Lord’s sake.”]

In time, my hatred for Church and religion took a turn that even I considered alarming, for I’d come to regard them as the greatest of all evils, blaming them and them alone for everything that was wrong with the world. When I encountered priestly vermin and churchy old ladies in the street – and there was no shortage of either in Graz – felt an urge to spit.

During my days on the road, I freed myself of this hatred thanks to the insight that I had been berating a doubtless influential, but nonetheless epiphenomenal feature of capitalism. Contemporary history, or questions of prioritization in sizing up the enemy. As an atheist, I soon enough felt, once I’d become a Marxist, perfectly indifferent toward religion and the Church.

In the late 1960s, I had to do some film work with a few human wrecks addicted to weed. All at once, I recognized different expressions of an irrationality I already knew. Anxiously, I sensed that something worse was involved (faith in Jesus is indeed supposed to have “saved” many people from smoking marijuana) and, for some time now, have suspected and feared (helplessly) the onset of a wave of irrationality, religious obsession, and escapism (served up, this time around, with Asian hoopla). A matter that had, for me (and my generation), been swept aside as a self-evidence, no long even of intellectual interest – religion – is back on the agenda for certain strata of today’s youth, and is even thriving. I might well, then, meet a pretty twenty-year-old girl who believes in the good Lord! I’ve dwelt on this at such length because it has been my misfortune to encounter, for the first time, a familiar negativity in others, members of the younger generation, that was supposed to have become (at least tendentially) a thing of the past. In future, everyone will have to acquire the levelheadedness to take such blows to general progress in stride.

57.

Once upon a time, the chances for a WDR series that was to be called Everyday Pleasures weren’t too bad. Music for Hartmut B., fashion for Harun F., and food and drink for me: a chef whose job is to bring each newly opened hotel in an international chain up to snuff is married to an exceptionally smart, pretty woman who, albeit sensual, takes no pleasure in food or drink. The chef accordingly engages in a few improbable adventures in order to teach Madame how to have fun being a glutton. To that end, he has recourse to a rental company (the dramaturgical switch tower in every episode in the series) that rents out not just things and human beings, but feelings as well, and, for an extra charge, even “authentic feelings.” We wanted to bring up a few points in movie-essay style about the status that consumption, luxury, and pleasure have in different social classes, and we thought – as I still do today – that this could be done most effectively in a series that kicked off with a striking attention-grabber. The member of the WDR’s tele vision-film department responsible for this project, the script editor Joachim von M., knew us from the DFFB. He acted (at least at this stage) as if he were very much taken with our conceptions, discussions, and work.

Then the Big Day arrived: the crucial discussion with the head of the department. Ingrid O. and Ursula L. accompanied their husbands to Berlin’s Tempelhof airport, and I had shined my shoes: what was at stake was our début, after all, two to three years of work and, at last, a little moolah. But Dr. Günter R. didn’t go for the idea at all; nothing about it was “realistic” enough for him. What he meant by that became clear when he objected that there were no such rental companies in the real world. Hartmut B. and I were struck dumb; we felt like mice facing a snake. Harun F. started flattering away, approving every one of Dr. Günter R.’s criticisms so fast that the worthy man couldn’t refrain from making the cynical remark that Harun wouldn’t get very far with him if he continued to be so opportunistic. Joachim von M. didn’t utter a word, now, in defense of our project. The Boss noticed that too; he called his script editor a lamentable coward in our presence, obviously not without pleasure. But that didn’t bring the curtain down on the tragicomedy: as, sitting in a pizzeria, we were trying to get over the shock of being rejected, “our” script editor also began to get his courage back: once he got home, he was finding our work excellent again …

At the time (early 1971), I had imagined a discussion about a TV-film project differently, of course. The exposé netted me 1,500 marks – the only fee I’ve received for a TV drama to date.

58.

Apropos quotations. What is regrettable is less the inflationary trend in quoting than the abstract, theologically conceived, dematerialized way of quoting. An opinion of Lenin’s is well-nigh meaningless or even misleading unless it’s clear to the reader where, when, and under what conditions it was aired; for example, before or after 1905, during the Revolution or after it. It is true that the slogan “down with the class enemy!” is always correct, but the decisive consequences can be discussed in detail only with reference to the time and place of its utterance: in Germany in 1930, or 1940! Furthermore, when the subject of discussion is work on socialist film in West Germany, one is well advised to appeal rather less to Lenin, unless one wishes to ascribe to him the power to judge our present-day conditions as accurately as he did the cinema of the USSR shortly after the civil war.

- 1Julian Volz, “Prolegomena. Straschek 1963 – 74 West Berlin (Filmkritik 212, August 1974)”, Sabzian (2022)

This text was originally published as “Straschek 1963-74 Westberlin” in Filmkritik vol. 8, no. 212 (August 1974), and will be published in 4 parts on Sabzian in the coming months.

CINEMATEK and the Goethe-Institut Brussels will dedicate a retrospective and an exhibition to Günter Peter Straschek in June 2022.

This project was realised with the support of the Goethe-Institut Brussels.

With thanks to Karin Rausch, Julian Volz and Julia Friedrich and the Museum Ludwig Cologne for providing the english translation.

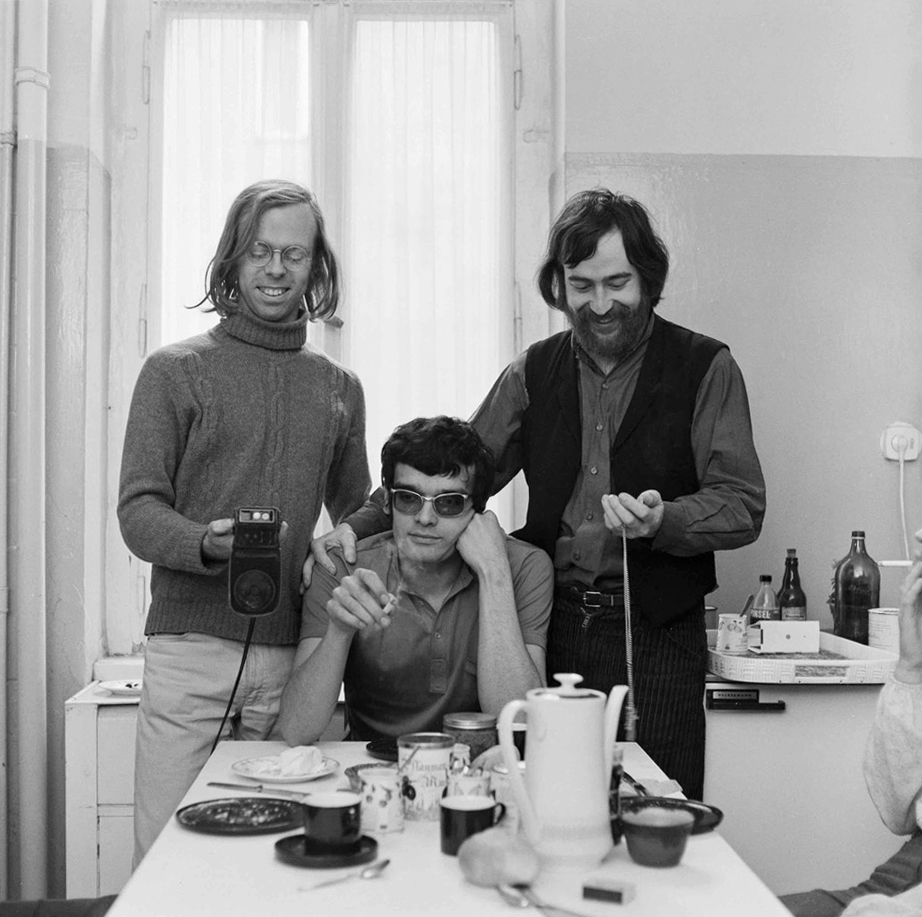

Image (1): Set photo of Labriola (Günter Peter Straschek, 1970). Photo: Michael Biron.

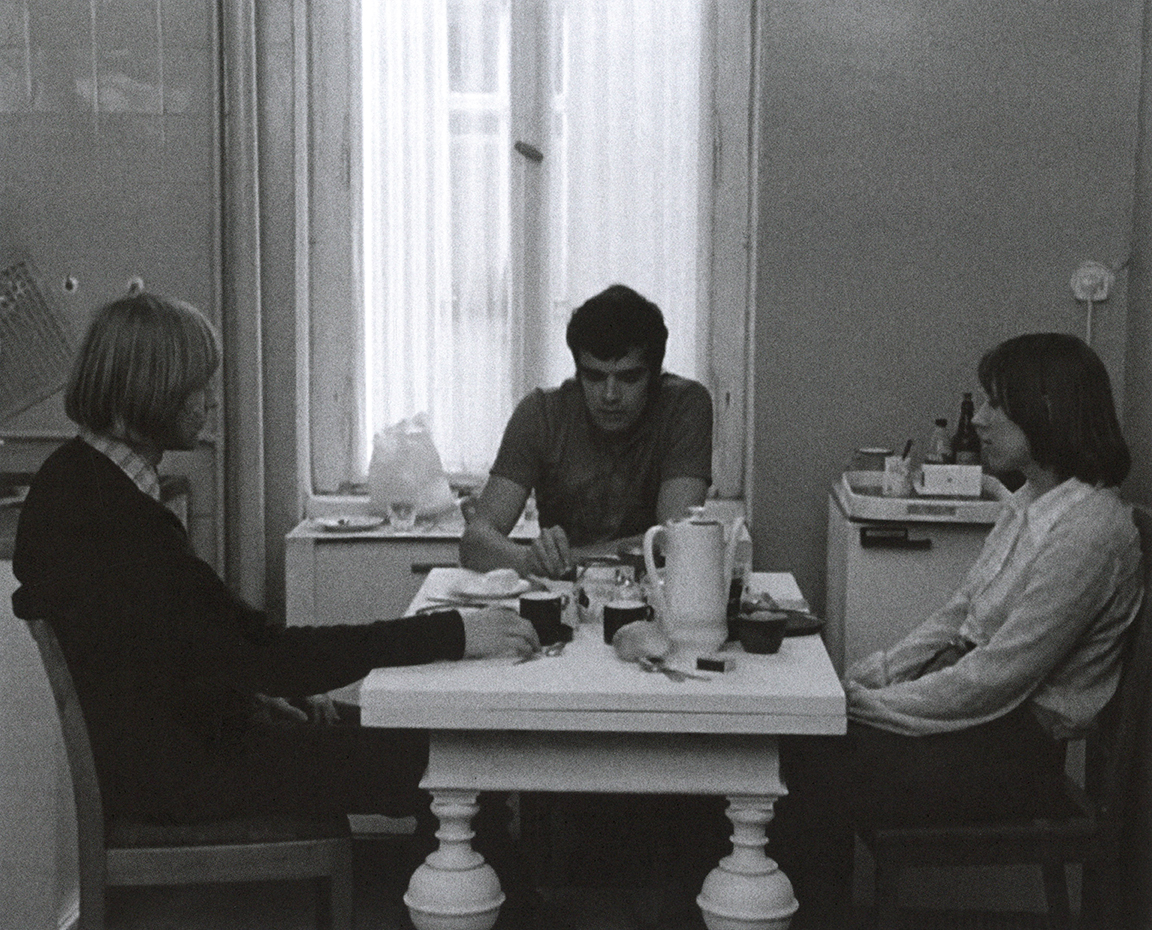

Image (2): Hurra für Frau E. (Günter Peter Straschek, 1967)

Image (3): Günter Peter Straschek in Es stirbt allerdings ein jeder, fragt sich nur wie und wie Du gelebt hast (Holger Meins) (Renate Sami, 1975)

Image (4): Gitta Alpar in Filmemigration aus Nazideutschland (Günter Peter Straschek, 1975)

Image (5): still Labriola (Günter Peter Straschek, 1970)