Notes on the Subject

The beautiful thing about Anne-Marie Miéville’s films is the way in which men and women are always angry (especially the women). Angry of loving, angry of not loving, of not being loved, angry their parents are there to badger them, angry they’re no longer there, angry the others don’t or, more often, the other doesn’t understand them. If we had to give a title to this work in its entirety, it could be, in the way Marivaux talked about the surprises of love, “The Quarrels of Love.” But that’s provided we don’t consider them fits of temper, transitions from a non-angry to an angry state, that we precisely don’t consider them as sophisticated banter in the style of Marivaux (or in their Rohmerian version): no, a permanent, maybe even a natural or an ontological temper; a temper which is too easily taken for “pride.”

There are the words of temper, which are its meaningful pocket change: the “oh! damn!”, the “my god!”; or the utterance launched by Agnès, who is on the phone, in order to get rid of one of her men (Hans, undoubtedly, the indiscrete lover): “je peux-te-pas-je-te-peux”, which is violent for being so restrained. Above all, there is the tone of anger, which is always a restrained tone in this film: “Listen, we agreed: not every day” (also said to Hans) – which is said in a manner not unlike Delphine Seyrig’s criticism of her stepson in Muriel; the dear subject’s stories are always stories of restrained exasperation, dominated by affection or tenderness, or maybe by weariness or fear.

To restrain anger, to protect it from exploding, strongly affects the body. In this film, there is a sort of burlesque of the body in the grip of anger, of the body that constrains and contains. More or less pure burlesque scenes – sinister, even, or darkly humorous: the meetings while “jogging,” the driver who is dissatisfied with his radio suddenly missing a lower register, the grandfather who drops that he’s “bored stiff” with Odile’s smooth smiles. The burlesque culminates, simultaneously with the sinister (which would be horrible, if it weren’t so sinister), in the abortion clinic. “So, will she take the soup, the little ‘termination’?”: we don’t see the dinner lady who asks Angèle the question; but we do understand that she comes from an absurd, undoubtedly obscene, definitely comical world. Angèle could have laughed; but she gets angry. Angèle is at the heart of anger. During a tense off-screen conversation between her and Agnès, her mother, the latter mimes a boxing match with François in slow motion (one of burlesque’s key tools).

Again in the register of anger are all those who aren’t and almost can’t get angry. The singing instructor: the smiling man (who never laughs); he’s not the one to get carried away and prophesy like Kane's maestro; we will never know what he really thinks about Angèle’s Queen of the Night. Agnès’s friends with benefits, Hans who “doesn’t understand why she’s angry” when he refuses to have dinner with Odile, François who has chosen the infantilism of little bed games and ridiculous nicknames: all those who aren’t family (François will fleetingly become capable of an act of violence when, at the grandfather’s funeral, he puts an end to too much social comedy on behalf of the clan).

The dialogues are battles, and the denial of these battles. Lou, just like Mon cher sujet’s character, spends her time saying no, but it’s just a propaedeutic: “in order to learn how to say yes, you have to start by being able to say no”. The film is called Lou n'a pas dit non and ends with a dialogue between statues, a series of agreements (of a man to the proposals of a woman). The subject of this film is the relationship between men and women: like the relationship between ages, that between the genders of humanity is painful and necessary, because women and men don’t have the same relation to subjectivity. When Lou and Pierre go on a pilgrimage to Rilke’s grave, there’s a moment when they have to leave the main road; we see them from behind the car. Lou: “We will have to turn to the left.” Pierre: “No, to the right.” In the next shot, a car, filmed from the front and from a distance, calmly leaves the main road towards the left side of the frame, but enters onto the road on the right. The relativity of directions is according to the adopted objectivity. Lou is right, but at the cost of a double inversion: that’s her dialectic.

The possible and the impossible also separate men and women: they never have the same definition. The shots also seem to be angry with each other, and the image angry with the sound. The enjambment of the soundtrack, the convolutions and weaving that makes it cross and re-cross the image, sometimes preceding or following it, sometimes doubting it from afar, aren’t just simple stylistic choices, but a sort of exacerbation of the irreconcilability of both. The man she loves – she, Agnès, the cher character of Mon cher sujet – doesn’t love her the way she would like: their conversation on the phone doesn’t feel like a conversation but like an interference. The phone in Mon cher sujet always works like this: you hear, you see. You see one of the persons speaking and you hear him, or not; you hear the other, the invisible one, or you don’t hear her. The phone is a crossroads of non-responses, as a long scene from Lou n'a pas dit non theorizes: established, yet low voices; voices in a carefully chosen tone, some of them recognizable. “His voice draws his mouth, his eyes, his face, draws his entire, inner and outer picture for me, better than if he were right before me” (Bresson).

In the disagreement of image and sound, the recurring figure is that of the chiasmus. From Angèle to Carlo, we go through mixes of music: from Mahler to saxophone improvisation, simultaneously with the image passing from a close-up of Angèle to the brass mouthpiece of the instrument. If Angèle is primarily music, Carlo is primarily exclamation (for quite a long time, he coincides with his first reply, his “Oh! Damn!"). Or, later on, the Léo Ferré song which passes from the non-location of film music to the Walkman that was – as we notice too late - already on Angèle’s ears. The only images that aren’t angry with their sound are obviously the images of live singing.

What can a shot do? If it doesn’t a priori look for reconciliation (with other shots), it can do anything, since it no longer depends on itself, on its capacity to listen, to watch, to “do” the image (Beckett: “now it’s done, I’ve done the image”). In order to film the statues, Lou most certainly doesn’t want to know their “history” (to come into contact with the image, the genetic point of view is not the right one; you need to approach it from the side of immanence). The shot is a kind of solitude, and we understand very well that if there is a musical model for this way of editing (Anne-Marie Miéville is her own remarkable editor), it is indeed Mahler, the kind of music that is angry with itself or even better, angry about itself, that continues to bring back the motif, but broken up, never melting into other motifs, always in conflict with them, always dazzling with its essential solitude (always transforming into an explosion, which is both Mahler’s genius and his limitation, and which makes us understand the small acting out by Pierre, Lou’s protagonist, who insults the old musician, or rebels against him).

The shot is not a unit of a chain, nor a fragmentary unity, the “little hedgehog” closed in on itself, which is so dear to the Romantics. The shot in Mon cher sujet is a kind of solitude; its connection [mise en chaîne] is often disrupted, unless the interval between one shot and the next is stressed, which happens even more often. The beginning of the film outlines the solid and definitive rule of this kind of editing. What appears to be an alternation mixes shots of people leaving a funeral with shots of Agnès decisively walking. But the alternation is in fact ambiguous: is the young woman heading to the church? do we need to understand the walking rather as a way of evoking a childhood memory, in a somewhat Buñuelian style? or is it none of the above and does she just walk, in the decisive way she knows how to do anything? The things she encounters: death and the visible sadness of a little girl in a tie, who could have been her in another life. The link is well established, where it should be established: between the shots. It is about introducing us as quickly as possible to the “dear” subject: life and death; but it doesn’t only or necessarily happen through the links and the certainties of the gaze and of conscience. In the following sequence, she is typing a text which is communicated to us by her inner voice – in a mixed up style: the links between the syllables are random; except that there is no randomness in the signifier. The opening sequence immediately identifies its key: no meeting is random; two gazes crossing are enough to make the signifier work. Two gazes, or two words of course, even if the crossing of words is more coded (in the third sequence, the chiasmi and dehiscences of the exchanged off-beat words on both sides of the phone disrupt even more than the ambiguous gazes exchanged with the little girl).

The shot never stops battling against itself, image against image, image against sound. The lines are said without looking for verisimilitude in the delivery (but without Bresson’s monotonous and “direct” tone. The literary quotes peppering or woven into the lines are said as if they were trivial phrases from everyday romantic life.

Who is the subject of Mon cher sujet? Two women, at least: one writes, but we only see bits of the writing and no one seems to want to read it, unless in the future (“I look forward to reading your article,” says François, as if he is going to taste a cake, or the bread Odile will later knead); the other sings, and it’s impossible not to pay any attention to that. She who writes would like, but doesn’t manage to be loved by men, or by certain men; she who sings is in the company of men. “O dark night, my mother, do you see what’s happening?”, Angèle says on her way to the clinic. By singing Queen of the Night – a little premature, perhaps, with respect to her vocal maturity – she becomes a potential mother, making her the definitive protagonist. When it comes to little Louis, he exactly fits the place of the great-grandfather who slipped back into childhood: a man for a man, closing the circle.

What is the subject of Mon cher sujet? Agnès’s lovers are different (especially in bed) – but exchangeable, or never really there. She mostly spends time telling both to François and to Hans about her other, older, ended, undoubtedly missed loves. The union of bodies is always distant, problematic or at least undetermined; the bodies are dressed, aware of being polished and clean and presentable. There is no letting go; there is no noticeable mortality in these bodies. As Plato said in a dialogue fragment, there are those whose fertility resides in bodies, and those who rather look for Beauty. The union of man and woman, the union of bodies, only exists in the union of the mind: through the hand, through the gaze, through what binds without bringing enjoyment – as with the fiction of the sculpted couple that ends Lou n'a pas dit non.

The subject of all the films in the world is: I love you-you love me, or rather, I love you-you don’t love me; I and you, distributed among lovers and parents. This film’s subject is the subject of all films: my “dear” subject, my dear “subject.” A subject that mixes and makes these two series of I and you respond to each other mirrorwise: the children the lovers, the parents the loves. Angèle and Carlo are entirely caught up in thinking about lineage, about transmission; that’s why time doesn’t have much effect on them, on their bodies and on the subject they embody. The story told lasts at least five or six years, but rather than of aging, we get the impression of a certain transfer in time: generations that move in solidarity. The story of Pierre and Lou is a little different. They only arduously, uncertainly succeed in coming together in a kind of mutual acceptance, in the pacification of differences, because they stay children of their childhood above all (key role for the two opening scenes – less psychological keys than emblems: Freud taken literally?).

And, to end with, the subject of all the films in the world is: “tell a story.” But the story is always the same, we already know its bends and whims before it is even invented: the only thing that matters is the end of the stories. Stories need to end, because they are only the fact of telling a story. The old man puts it well in Mon cher sujet: “How could you tolerate this whole story without the certainty that it will end?”

Originally published in Anne-Marie Miéville, edited by Danièle Hibon (Paris: Galerie nationale du Jeu de Paume, 1998).

With thanks to Jacques Aumont

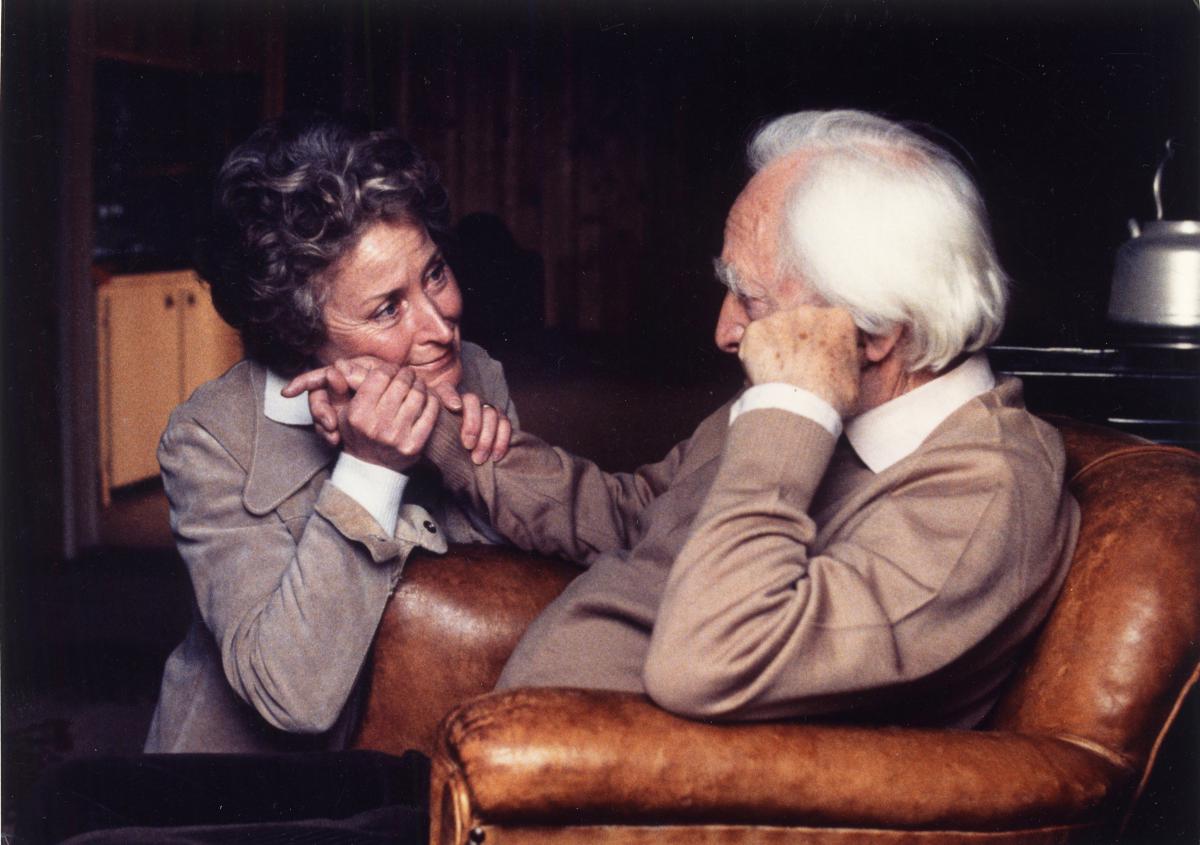

Image (1) and (2) from Mon cher sujet (Anne-Marie Miéville, 1988)