Straschek 1963-74, West Berlin

Part 1

The title of the text “Straschek 1963–74 West Berlin” is as simple as it is informative: it is a subjective, self-reflective insight into Günter Peter Straschek’s eleven years in West Berlin. During this time, he was many things: filmmaker, film historian, film theorist, writer, politically active in the protest movement of 1968 and part of the first generation of students at the Deutsche Film- und Fernsehakademie Berlin [German Film and Television Academy Berlin] (DFFB). Straschek’s fellow students included people like Helke Sander, Harun Farocki, Hartmut Bitomsky, Johannes Beringer and Holger Meins. His essay provides unique access to the film-aesthetic and -theoretical debates and practical-political discussions of a generation of filmmakers who were to fundamentally renew filmmaking in Germany, and whose political and formal experiments made the preceding generation of Oberhausen Manifesto filmmakers look staid. Born in Graz on 23 July 1942, Straschek merged his experiences and interests from his West Berlin period into one condensed virtuoso composition for the magazine Filmkritik. Straschek created a constellation of various text types, such as political-theoretical and film-aesthetic reflections, anecdotes, diary-like entries, letters or even feeding instructions for Danièle Huillet’s cat. It is a text montage that most filmmagazine editors today would probably shorten considerably and change formally. The text owes its publication in this form to the spirit of the time, but especially to the editorial guidelines of Filmkritik, which was certainly the most prominent film magazine in the German-speaking world at the time.

– Julian Volz1

Bad intellectuals have never yet become good proletarians.

1.

As for the few things one likes and takes seriously – socialism, work, women – I am accordingly sensitive.

2.

Occasions for a résumé: after interviews in Hollywood this fall, a trip to Mexico, and several months in Cologne editing the series about emigration in the German-speaking film industry, I won’t be returning to Berlin. I’m going to take up residence in London instead. I’ve never regretted choosing (West) Berlin and, over the years, I’ve come to like this unique city. But eleven years is enough. In the end, it got boring after all. (Considered at the national level, West Berlin seems to me to be the “most free” and most complex of all German-speaking cities; measured on the international scale, however, it falls rather short of the mark.) I have an “imperative” desire for a change (for a temporary change in my linguistic and cultural surroundings as well) and a chance to discover-something-again, and London is a splendid city from my standpoint – the British Museum, British Film Institute, and Imperial War Museum are first-rate places to work. I don’t plan to change anything about my writing activities: I’ll continue working for institutions based in the Federal Republic of Germany, living in London rather than West Berlin on fees paid out in marks. Thus the complementary factors of mobility and life without a family will fuse to form defining features of a man with privileges but without means.

3.

A socialist collecting stamps doesn’t make a Marxist philately. I take the liberty of putting it that bluntly in the face of a rampant voluntarism and an amazing ignorance of economics. For, in the past few years, people have been cultivating the illusion that capitalist forms of production can be (adjectivally) eliminated thanks to the “correct consciousness” of those taking part in them.

4.

Oeversee Realgymnasium in Graz; or, school as a positive experience of fear. I’m not talking about my formal education (history ended with the Habsburgs and sex was explained with reference to bees) at the hands of teachers who were either Catholic reactionaries, royalists, or Nazis who went on pilgrimages to Bayreuth. I mean Insight into helplessness in the face of stupidity and oppression, praise for conformist mediocrity, and the loss of the ability to communicate that they engendered in me. I had soon fallen into disrepute for being a demagogue; a student association that I founded was, even then, organized along rigid, atheistic lines. The fantasies were still schoolboyish (smearing Teacher with honey and throwing him into a pit full of ants; tying wet leather around Teacher’s scrotum and laying him out in the sun to dry, and so forth). Professor Doctor August H. was a short little fellow, but that didn’t make him any less a Nazi pig who behaved like a trainer at boot camp. He may still be teaching gymnastics and philosophy today. Boxing students on the ears, he drove them down the corridor all the way to the back wall; he was notorious for his brutality. Once he told another teacher about me (in title-hungry Austria, even ordinary secondary-school teachers are called “Professor"): “I know the breed.” I leaped to my feet, shouting: “I’m no breed.” This Professor brought me into his office, thrashed me, roared in my face. Feverishly, I thought things through. There were just two possibilities: kick him in the balls or lodge a complaint with the school board. But I was terrified, and my parents, wringing their hands, begged me to drop the idea of a formal complaint for fear of a scandal. With their long experience of life, they explained the matter to me in detail – the teacher would get off scot-free, and I’d be transferred and blackballed. This helplessness in the face of coercion and mini-terror (in a school in Austria’s Steiermark in the 1950s) left an indelible impression on me. I very distinctly remember that, during this incident and many others, I trembled, before falling asleep at night, with fear at the thought that I might turn into a Communist. This had nothing to do with political awareness yet. It’s just that, in the public consciousness of a city as fascistoid and anti-Semitic as Graz – the “City of the People’s Insurrection,” the title it bore from 1938 on – the “Commies” constituted a group that was so utterly peripheral and universally decried that I felt drawn toward them and could only move closer to them as a source of protection and potential resistance, although I suffered anxiety attacks due to the kind of family I grew up in (petty bourgeois Social Democrats with the mindset of the upwardly mobile middle class). I was in desperate quest of solidarity; where else could I have found it but with the Communists? Instead, in my last years in Austria, I took “solace” in art and my role as bogey of the middle class. The upshot was that I was farther than ever from resolving the conflict. What’s more, I’d been expelled from my Gymnasium and all public schools in Austria because of my abysmal marks.

5.

I have only to hear phrases like “songs are weapons” or “cameras are rifles” to feel like puking. The same fraudulent self-delusion again and again (because some people can’t come to terms with the fact that they work in the relatively unimportant cultural field). As if there were no difference between a protester plucking away at his guitar and someone tossing a grenade. As for the critics who take satisfaction in the fact that so many movies about Chile are screening at the Short Film Festival in Oberhausen, what gives them the right to churn out catchwords about how “cameras are rifles” in the face of a brutal counterrevolution that was partly the consequence of a weak Popular-Front government’s failure to arm the masses? Is it cynicism or well-meaning imbecility or run-of-the-mill leftist opportunism? All that’s certain is that such people can never have held a gun or movie camera in their hands.

6.

Always been a movie fan, even if my passion was literature until the early 1960s. Graz had a lot of movie theaters, relatively speaking. My clan looked askance at frequent movie-going, especially in good weather, when I was supposed to go on hikes or to the outdoor swimming pool. It was my great-aunt, of all people, a card-carrying member of the Austrian Communist Party, who told my mother not to let me go see Quo vadis, in which, according to her, Christians would be devoured by lions (unfortunately, it turned out that nothing of the sort was to be seen in Quo vadis ...). I often played hooky from the Realgymnasium the whole day long; the nonstop movie theater in the Herrengasse was a safe haven. I had a violent altercation with Jochen R. († September 4, 1970, in Monza) in the opera-house cafe over whether Burt Lancaster had been plugged by Gary Cooper or done in from behind by the Frenchwoman (Vera Cruz). The first naked movie bosom appeared in The Ship of Condemned Women. Motion pictures became an occasion for jacking off. After that came “good movies,” art cinema. I seem to have become a cineaste while on the road, since it was then that I saw pictures in the original versions in Greece, Turkey, Israel, and Cyprus, without being in the least put out by the fact that I couldn’t understand a word of the language. In West Berlin, the rate at which I went to the movies rose to once a day, jumping, in my years at the DFFB [German Film and Television Academy Berlin], to three or four films daily; I saw certain works between ten and twenty times. After that, I had the sense that I’d understood enough; I felt satiated. I’ve avoided festivals for years; they disgust me.

7.

Moscow contends that the struggle between socialism and capitalism is being increasingly displaced onto the terrain of ideology, where it is being waged with undiminished intensity. I too fear that, when I think of Sviatoslav Richter or Roland Matthes.

8.

The project on emigration in the German-speaking film industry after 1933 very closely approximates my idea of the kind of work I should be doing in future. I’ll be busy with this undertaking for about four years. It will culminate in a TV-film in several episodes, and I’ll also be publishing a book (in two volumes); I can also use parts or interim results of my work on radio, in periodicals, and for lectures. Researching the project will involve a great deal of communication and allow or even require travel. The topic is multidimensional and thus corresponds to my “capacities for integrating a wide range of elements”; what’s more, it’s anti-metaphysical in that one can keep sight of the big picture and anticipate when the project will materialize. I’m pretty slow and prefer to work on two or three long-term projects at once; it goes against my grain to have to jump constantly from one theme to another (for TV, for example}, usually just when one has begun to get a handle on the subject matter. On the other hand, I don’t like lifelong undertakings. At any rate, I don’t believe I have any further ambitions to speak of in the history of cinema, although there are two projects that would very much appeal to me (if I could find collaborators): an investigation of the electronics industry, bank capital, and motion-picture production, and a comparative study of movie companies.

9.

Austria; or, fascism + dilettantism = resistance: “While breaking into the apartment of the Jew Viktor Stransky, Stubenbastei 12/3/17, Vienna 1, a member of SS-Standarte 89, authorized business agent Willibald Schiebel, b. 1911 in Vlenna-Otta kring, fell to his death while swinging out of a window over the airwell on a rope” (SS Security Service report of April 4 and 5, 1 939, National Archives, Washington, DC, USA, Microfilm T84R15 43 173).

10.

In our fourth year at Gymnasium, we were required to keep a “book diary"; in other words, we had to describe our extracurricular reading. The only books I praised were Richard von Frankenberg’s books on race-car driving. In my reports on Maeterlinck’s one-act plays, I identified Baudelaire and Verlaine as, for me, “certainly unknown Frenchmen.” The German teacher, a sweaty K. H. Waggerl fan, wrote “symbolists” in the margin. By the following year, I had not only “familiarized myself” with Baudelaire and Verlaine, but had also reconsidered some of my earlier views after re-reading and produced revised versions of my reports. I continued to do so In the years thereafter, thus keeping a record of the shifts in my opinions. Ever since then, I’ve not only had a preference for essayistic/ autobiographical prose pieces that are subject to constant reassessment and revision, but have also appreciated the need for different versions and editions; I was already thinking, back then, about the possibilities for modifying a work of art by the way one distributed it. In Graz and Vienna, one heard all the time that BB produced different versions of his poems, “one for the West, the other for the East.” “Now I ask you,” people would go on, “which is the right one?” After a moment’s thought, that seemed to me to be perfectly correct. I saw right away that film and cinema have a disadvantage: namely, the impossibility of altering a product once it’s finished (in the economic, cinematographic, and legal senses of the word). With Holger M., I tinkered around with interchangeable segments in connection with the Frankfurt secondary-school student film project, but we didn’t get anywhere. [Initial successes are supposed to have been scored in computer-movie research.] The problem is closely bound up with questions of socialist filmmaking – that’s why.

11.

I’m given to complaining that there are fewer and fewer women capable of appealing to me as female personalities. If I were a woman, however, I’d be wringing my hands. Shallow talk about change and emancipation; the sublime terror of “wash the dishes for once”; self-satisfied “be-a-man” posturing; cowardly and insensitive, which, with the steep rise in the art of Jesuitical argumentation, is brutalizing human communication; no good in bed – in short, what knocks around this country in the way of masculine types (bearded and sporting wire-rimmed glasses) must be appalling for a woman.

12.

The two-volume edition of BB’s Arbeitsjournal [Work journal] (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1973) comes with a supplementary booklet of notes by the editor, Werner Hecht. Hecht is a recognized BB-specialist and East Germany is, generally speaking, known for its scrupulous editorial work. I myself have long been disgruntled over the sloppiness of a lot of editorial work in this country and still am, even if my sensibilities have been blunted by the mores prevailing in film literature. Yet, faced with the indifference to his readership that Mr. Hecht displays in the Notes accompanying his edition of so important a work of BB’s, I got incensed all over again. On just a cursory flip through, I spotted incomplete or incorrect information on practically every other page. Can Suhrkamp, too, have failed to catch these errors? Here are just a few examples, with no indication of the sources (for my corrections):

p. 8 “Koloman Wallisch . . . led the Styrian workers’ struggle during the 1934 February Uprising and was shot that same year.” The Austrofascists hanged Wallisch in the prison in Leoben on February 19, 1934.

p. 11 “In the late 1 920s, Carola Neher had settled in the Soviet Union with her husband” – where she fell victim to Stalinist terror!

p. 28 Bernard (not “Bernhard”) von Brentano, d. 1964!

p. 36 Einar Otto Gelsted, d. 1968!

p. 39 By “H. Lawson” (p. 266) or, alternatively, “Lowson” (p. 586), BB would appear to mean the critic and screenwriter John Howard Lawson (b. 1894).

p. 47 Marshall Timoshenko, d. 1970! Herman (not “Hermann”) J. Mankiewicz, d.1953!

p. 50 Ben Hecht, d. 1964!

p. 51 “The actress Salka Viertel emigrated with her husband, the director Berthold Viertel, to England and America.” Salka Viertel (b. 1889) always used her maiden name, Salka Steuermann, as her stage name. In 1929, she settled in Hollywood with her husband. Berthold Viertel moved from Hollywood to England by himself in 1933.

p. 54 “Helene Thimig… went with her husband Max Reinhardt to the USA in 1937.” Reinhardt emigrated to the USA in 1934, where he married Helene Thimig in 1935.

p. 56 “The German actor Robert Thören was employed as a screenwriter by MGM.” Thoeren always spelled his name with oe, even as an actor in Germany prior to 1 933; after emigrating to France in 1933, he started working as a screenwriter. Thus MGM never hired “an actor named Thören . . . as a screenwriter.”

p. 60 “Curt Götz (1888-1960) appeared in most of his plays and movies together with his wife, Valerie von Mertens.” Curt Goetz (not “Götz”), who spelled his name “Kurt Götz” until the mid-1920s, was married to Valerie von Martens (not “Mertens").

p. 61 “Alexander Granach (1880-1949)… went to the USA in 1933.” Granach lived from 1890 to 1945 (not “1880-1949") and emigrated via Poland to the Soviet Union in 1933, which he left to settle in Hollywood in 1939.

p. 77 Clifford Odets, d. 1963!

p. 84 “The movie Hangmen Also Die (directed by Fritz Lang) was produced by the motion picture company United Artists.” Officially, this movie was only distributed by UA. It was produced by Arnold Pressburger’s Arnold Productions.

p. 89 “Günther Stern (b. 1902). published under the name Guenther Anders.” On p. 203, in the index of proper names, one finds “Anders, Günther; see Guenter Stern.”

p. 93 “The actor Paul Henried (formerly Paul von Hernreid, b. 1907) moved to England in 1935.” Paul Georg Julius Ritter von Hernried-Wasel-Waldingau was born in 1908, went by the stage name of Paul von Hernried in Germany-Austria-England, and in the USA he called himself Paul Henreid.

p. 128 “The movie director Preston Sturges (1898-1 959) directed three movies, which came out in 1944: . . . ‘The great movement.’” Sturges directed a total of twelve feature films, three of which came out in 1944, among them The Great Moment. There are also a great many smaller slips in the book. And the index of proper names, because it was obviously put together by a poorly paid assistant, is especially faulty. I don’t deny my pronounced susceptibility in such matters, my neurosis for exactness. But I insist nonetheless that “our” work, or other work that is for whatever rea son important, should be reliable, and that it should be easy for readers to verify its partisanship and source material down to the smallest details. Furthermore, a pirate edition of BB’s Work Journal would display the quality characteristic of BB only if it were accompanied by a list of emendations of these scandalously error-ridden Notes.

13.

I’m not by any means an easy-going person, and that holds for my attitude to consumption as well. In Munich’s Schwabing district, I don’t just feel like an outsider; I’m downright nauseated by its parasitical lifestyle, its throng of fashion-world prostitutes and movie-industry pimps, of barflies and imbeciles of the kind that flock to the opening days of exhibitions. Nothing but banks and department stores, with boutiques and antiques shops in between, because, thanks to a repressively perverted demand for jewelry and fashion, everybody wants to rise to the rank of third-class entrepreneur. Admittedly, West Berlin is a unique city because of its exceptional political situation. But if I’ve truly learned to like it over the years, the reason is also, and especially, its relative shabbiness.

14.

What would comrades say about left-wing doctors who don’t know where the appendix is, or socialist lawyers who have no notion of what legal clauses are? Only socialist artists, first and foremost filmmakers, can get away with anything they can. Mao Tse-Tung’s demand that intellectuals serve the people implies, among other things, a call for intellectual professionalism (this is studiously ignored). That is why I so intransigently campaign for socialist consciousness & specialized knowledge in a praxis-oriented combination. And because, in the present conjuncture (despite many recent insights) socialist consciousness (often confused with goodwill) is faring better than specialized knowledge, I overemphasize expertise. A left-wing _______ (fill in the blank with the name of any profession) has to know more about his job than the competition, and be able to work more professionally. He should never make up for professional defects with verbal radicalism or other platitudes.

If self-identified socialist filmmakers were to win a television station in a lottery, they wouldn’t even be able (with their whacky ideas and ignorance of the practical side of things) to put together one evening’s programming. That needs to be said for once. It also needs to be said that our movies would have been more effective if they’d benefitted from greater formal and technical attention, and greater sensitiveness, all the more so in a day and age of generalized bastardization and state-sponsored dilettantism. I myself, when I began my studies in the film academy, was among the champions of an ideology that pooh-poohed formal problems as such and naively assigned priority to “the message.” Having changed my mind, I would like expressly to underscore how much I consider the dismissal (which is, by the way, altogether un-Marxist) of formal-aesthetic questions and questions of craftsmanship to be a grave mistake on our part (on the part of socialist filmmakers)-and, given our blindness to the need to come to grips with the above-mentioned problematic, I would like to plead strenuously for the indispensable “extra measure” of technical and formal skills. My reservations about the Germanists, sociologists, political scientists, teachers ... or filmmakers who loll around while going on and on about socialism, but are poorly qualified in their field of specialization, must be understood as stemming from my concern about the degree to which the neglect of so crucial a matter, namely, professional qualification, has proliferated at our expense, thanks to misunderstood theses about (the pressure for) performance. Things should be prevented from going any further in the wrong direction and put back on track, regardless of our dilettantes’ standard complaint to the effect that that is “revisionist” behavior.

15.

From the private life of someone doing research on emigration in the film industry: on the phone, a woman confirms that her late husband, the producer So-and-So, was an emigrant. In our new project manager’s office, we discover that he emigrated, not from Nazi Germany in 1933, but from an Eastern European socialist country in 1949. “What difference does that make?” the man’s widow asks. After spending time in jail, seeing all their property confiscated, and paying an appallingly high exit fee, the family was expelled and frisked at the border; the woman was stripped stark naked and searched “everywhere, but absolutely everywhere” (I nod to show that I’ve understood). Whence the sixty-thousand dollar question for Marxist ethics: Does communism have a right to look for hidden diamond rings in “bourgeois cunts”?

16.

From orgasmic dysfunction to poor concentration to hair loss, Marxism as medicinal treatment has been very well received by the younger bourgeoisie. Its objectives have been less well received, or hardly received at all. That may sound brutal. Yet the fact remains that the socialist movement is indeed in a position, in most of its developmental phases, to help partisans and even sympathizers alleviate or cure such disorders, a legacy of their bourgeois past. Recently, however, this capacity has been misunderstood, breeding the eschatological tendency to consider Marxism a kind of doctor for intellectuals suffering from all sorts of little aches and pains. What I oppose, then, is the burgeoning tendency to transform social problems into psychological and pedagogical ones. Above all, more and more girls are flocking into the fields of psychology and pedagogy, seemingly unaware of the negative feminine role that they are thus once again prepared to don.

Especially, I would like to protest against the demonstrable trend that everyone, but everyone, whose grades aren’t up to par or who somehow can’t figure out what to do with life, never mind the whole mediocre crowd of students and intellectuals who have fallen by the wayside, now want to be teachers, simply because teaching has become the most obvious career to pursue. It has even been suggested that unemployed actors (a conceited, mindless professional group devoid of solidarity) should be herded into teacher-training Institutes that will spit them out as schoolteachers at the other end. This tendency, and the illusions bound up with it, is sure to boomerang soon enough: in the form of the children about whose welfare everyone pretends to be so concerned.

17.

As a child, every day at breakfast before being marched off to school, I read Graz’s socialist newspaper, to which my parents had (and still have) a subscription. The headline “Dien Bien Phu Falls” was my first political shock. The fact is that I’d been rooting for the brave encircled Europeans, the way they figured in the countless pulp magazines I’d read. I’m reminded of this on the twentieth anniversary of the victory. For a long time now, the courageous, bleeding Vietnamese people have been the object of my esteem and fellow-feeling: growing older.

18.

a) “Progressive” writers are an odd lot. On the one hand, they want to get involved, to turn their backs on their bourgeois existence and “ivory towers” in order to “change society”; on the other, they lapse back into their traditional hypersensitivity, freezing in their lachrymose poses, precisely when they’ve elicited an echo. If some moron from the CSU lights into a left-wing writer over beer with his cronies, the writer doesn’t hit back, but starts yammering about an “inadequately developed sense of democracy,” concludes that freedom of the press has been endangered, and so on and so forth. The artists who “want to change our society” really ought to stop reacting at a moral level to the normal – after all – reaction of the reactionaries, and to quit fluttering about like flustered chickens while signing endless protest letters. It goes without saying that the class enemy has to defend himself against our armchair revolutionaries. And although writers in Bolivia and Greece are indeed behind bars, we shouldn’t forget, in the effort to free them via PEN, etc., the many more hundreds of workers and peasants who are imprisoned and martyred in those countries and who may not even be capable of writing. It was more troubling for the bourgeoisie, too, that “its” Thomas Mann was stripped of his honorary doctorate or that “its” “eminent Jewish doctors” were forced to emigrate than that little Abie in Czernowitz was gassed, to say nothing of the fate of gypsies, gays, communists, or delinquents. A bit more toughness & endurance and a bit less self-pity would stand our oh-so-critical artists out to change society in good stead.

b) If this Solzhenitsyn isn’t a lousy anti-communist, I’ll eat my hat.

c) For someone like me, who feels greater empathy with the underprivileged and oppressed than his cynicism may lead people to believe, the mind-boggling scandal resides in the fact that a state calling itself socialist, as the Soviet Union does, has to the present day not managed to write down and publish its history on even a bourgeois-positivist level, let alone with materialist insight. What kind of a country is it in which some forty-five thousand books are printed every year, while a Trotsky hasn’t been mentioned for decades? What kind of party is it that, for decades, has covered up its political history and political deviations, so that the fashionable religious incrowd, motivated by anti-communist hatred, is able to formulate elements of the truth in pamphlets of the most tendentious, reactionary stripe? As if it could ever be detrimental to socialism to bring errors to the light. What else could our slogan “learn from history” possibly mean?

19.

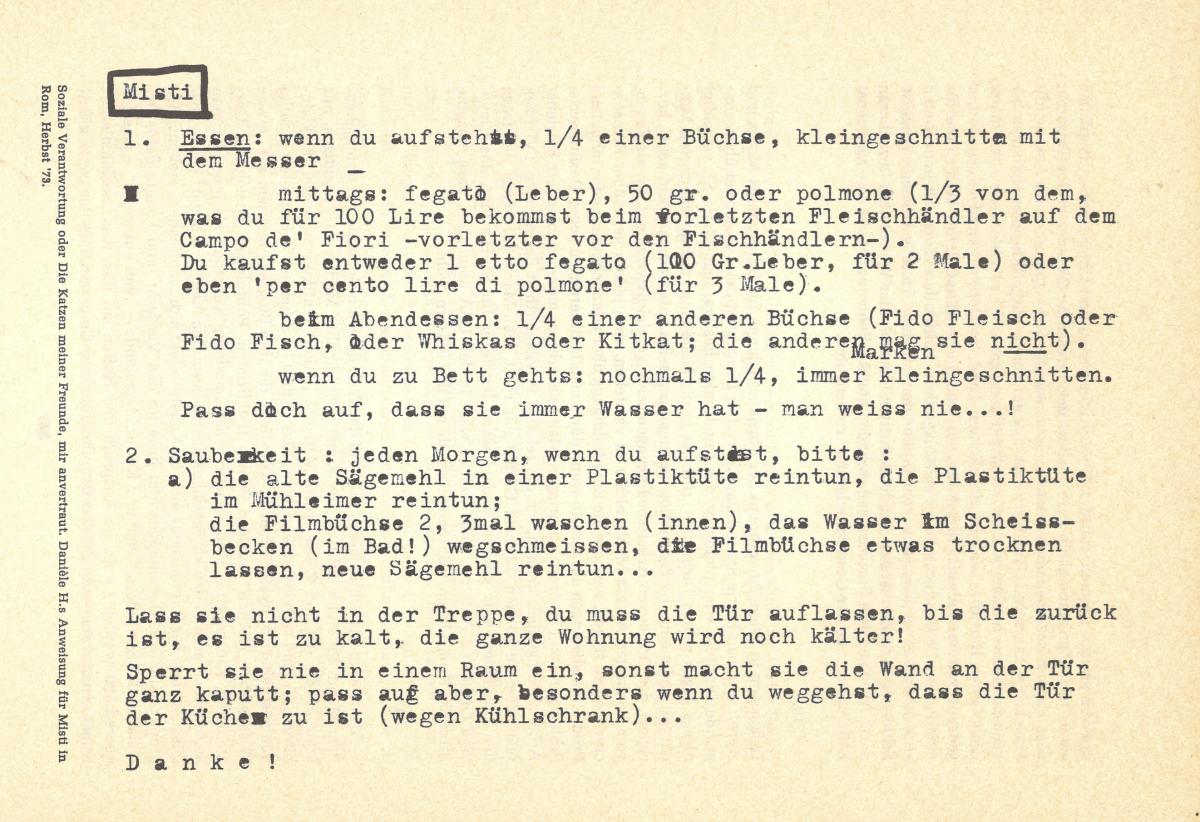

A discussion in 1974 in Vienna, where Jean-Marie S. and Daniele H. were recording the music for Schoenberg’s Moses and Aaron. The conductor Michael G. poked fun at the radio orchestra for its lack of discipline and intelligence. Jean-Marie S. defended the orchestra against its conductor, likening it to an underprivileged minority, and said that it faced the corresponding conditions of production. Michael G. contradicted him: the orchestra, he said, enjoyed relatively decent working conditions. I stepped in with the remark that, though I understood nothing about music, the concrete occasion for their discussion, I often wondered, in the case of television crews, where the excuse of unacceptable or inhumane conditions of production ended, and from what point on one had the right to draw the line on indifference, sloppy work, and ignorance. I added that, in my opinion, one had to be familiar with other sectors and their working conditions to discern the relatively privileged position of most TV types. Michael G. said I was right. Jean-Marie S. wasn’t sure. I asked the conductor what, concretely, would be different if he were conducting the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra for S. & H.’s film. He answered: a lot. In the USA, it would be out of the question for some of the people in the string section to be reading detective novels while he was rehearsing with the wind players. Social responsibility; or, my friends’ cats, entrusted to my care.

20.

a) As if there were nothing worse in the world than a painting of a setting moon! I don’t shy away from defending art or those who produce it; it’s just that I find the modalities and methods of “left-wing” badmouthing of art to be petty bourgeois (and a waste of time to boot). It’s no accident that “art is shit” talk comes from failed, hysterical ex-artists who want to clean up their CV by “doing a stint as scholars” (political scientists, sociologists, Germanists, journalists, teachers – are they not closer to being “modern artists” than the dying breed that is still there to be made fun of in the classic arts?) It goes without saying that capitalism manifests itself in art products as well and that it does so at a propagandistic level here and there. I suspect nonetheless (and could produce evidence to ground my suspicion) that the value of art and culture is grossly overestimated in this country by “people like us,” and that the same holds for the claims and hopes attached to what bills itself as “socialist” art. Among the reasons for this reassessment of art’s social value are, of course, artists’ as well as critics’ longing tor continued importance and their desire to defend their identity. Among the factors we have so far recognized as socially determinant-and, in particular, in the face of economic problems-art seems to be an epiphenomena] domain that merits neither faith, consolation, and flight from the world nor scorn and boundless hatred. This holds especially when the valencies of a class struggle are considered-for bourgeois art (which is in any case just one limited historical domain of art in general). I don’t thereby mean to deny that the struggle has to encompass every domain; I wish simply to affirm that the energy invested in art criticism in the past few years hasn't paid off from the socialist point of view (since we really can’t say that the class struggle in West Germany has intensified, except in the KPD [Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands/Communist Party of Germany]). I wonder how leftists who regard an abstract painting, a Rubinstein recital, an opera, or a John Ford movie as the most reactionary, contemptible thing around would react to real abominations.

b) The discrepancy between subjective pleasure and objective cognition troubles me less where movies are involved than anywhere else. I never have been able to understand the constructions and contortions of certain, usually “conscious,” movie fans who go to great lengths to transcend impressions based on their own likes and dislikes by means of quasi-objective judgments. I, in contrast, don’t find it embarrassing to exploit precisely this subjective freedom. Everyone has (in cinema too) his or her favourite tearjerker: Jules et Jim plucks my heartstrings every time I see it (if only because of O. Werner and the music by Delerue, and despite the fact that Werner’s part is dubbed), even though it’s pure corn (like all of Truffaut). Whenever I hear the Marseillaise in Casablanca, I’m hit with a gulp of pathos. The Brando Western One-Eyed Jacks or sequences in The Chase get me incredibly excited. Simply, it would never have occurred to me to work my personal reactions up into a cracker-barrel philosophical theory of the chef d’oeuvre, the art film, etc. On the other hand, I’ve never been able to warm up to Dreyer or the “Russian films,” and have always been incapable of revelling in Kurosawa. I would emphatically like to increase the latitude for subjective judgment, because I consider discourse about cinema that proceeds by classifying (approving of) individual works to be fundamentally wrongheaded (for the details, see my Handbook against Cinema). The upshot: no one need blush for liking a crappy movie.

21.

The passage I found hardest to understand in everything I read as a child or teenager is the one in Sartre in which the hero plays with a woman’s pubic hair and falls asleep while he’s at it ... I started out reading pulp magazines under the bed covers with a flashlight, followed by adventure novels and, soon after, B. Traven. In secondary school I turned my back on the classics and read obscure writers as a form of protest: in the process, I discovered W. C. Williams, Khlebnikov, Saba, Ghelderode for Graz, and Henry Miller for myself. Since opting for cinema, I’ve read nonfiction almost exclusively (socialism, modern history, books on military subjects, film) as well as criminal history and detective fiction, for pleasure and also as dramaturgical training. I eventually caught up on a couple classics as well, out of interest-and was enthused and enraptured by J. W. Goethe’s Elective Affinities as well as by Adalbert Stifter. When, these days, I have any time and desire at all to read what is called “belletristic literature,” I invariably read the same writers: Nestroy, Stifter, Sealsfield, Pavese, Walser (Robert, of course), who were later joined by Thomas Bernhard (many of these writers are Austrians, as is easy to see).

22.

If a comrade from Schöneberg goes to a meeting in Kantstraße via Spandau, what is involved may be less a precautionary measure – shaking off an undercover cop – than the hope that there in fact is an undercover cop on his tail: a sign of intensified class struggle visible in the rear-view mirror, not just in words on a page.

23.

It is symptomatic that, with the decline of the movie industry, there has been a flood of secondary literature about a couple decades of cinematic history. The boom started in France and peaked in England, followed by the USA. Indications currently are that the once depressed market for cinema criticism has improved in this country, for more books about cinema have come out in recent years than ever before. This mini-boom is likely to last for some time. While research on cinema and movie-going got off to a later start in Germany than elsewhere, the present state of affairs (even if it is not very satisfactory) must mean, for authors and, still more, for publishing companies here, that we’ve now reached the level at which it should be possible to set things in motion: whether by translating the most authoritative works, compiling anthologies, or carefully conducting our own research in the field of a materialist theory of the media. Yet everything already goes to show that there is no desire to learn about, evaluate, and, in some cases, adopt or pursue results already available in Italy, France, Britain, the USA, and the socialist states, since this would only mean outlays; rather, one pretends that the foreign countries that have produced film criticism simply don’t exist, so that people in Germany may continue to muddle through somehow. I would rather not even begin to discuss what has the cheek to trade under the name of scholarship here: see Marion K.’s doctoral dissertation, which has now come out as a book: Film–Spiegel der Gesel/schaft? Versuch einer Antwort. lnhaltsanalyse des jungen deutschen Films von 1962 bis 1969 [Film – A mirror of society? Attempt at an answer: A content analysis of recent German cinema, 1962-1969] (Heidelberg, 1973), 22 marks. Something should also be said about prices for once. For example, I’m extraordinarily interested in Hans Scheugl’s thesis (If only because I take the opposite view), announced in a Hanser prospectus, that movie myths have changed because the role models on which they’re based have changed. But am I supposed to buy Scheugl’s book Sexualität und Neurose im Film. Die Kinomythen von Griffith bis Warhol [Sexuality and neurosis in cinema: Movie myths from Griffith to Warhol] for 48 marks? Is it really impossible to bring it out for less? The same publisher has issued a German edition of Truffaut’s Hitchcock book for 34 marks, with an abridged photo section at that, whereas a readily available English paperback edition costs only 18.50 marks. Jerry Lewis’s The Total Film-Maker costs $6.95 (a much cheaper paperback edition is probably already available); the German translation published by Hanser costs 24 marks. Is one not better advised to improve one’s insufficient English and read the cheaper originals? The vogue for monographs about directors, which soared to ridiculous heights in other countries years ago, has at last belatedly reached West Germany. The first volumes in Hanser’s “Reihe Film” series (on Truffaut and Rainer Werner F.} are supposed to appear this fall; books about Lucchino [sic!] Visconti, Keaton, Welles, and Lang are forthcoming. There already exist better than ten monographs as well as one hundred reviews of, or articles about, these world-famous directors. For a miserable fee (for the author) and a rather more handsome salary (for the editor), one has to pretend that one has thought up a great many new things to say about them. It never occurs to anyone to introduce filmmakers about whom no studies have yet been published, for that would, again, be too much work (since there’s nothing to crib, and one would even have to go see their movies}. Instead, we get compilations and, for the nth time, the same filmography for the same director.

The fact that there is no cinema criticism (or whatever one wants to call the discipline) in West Germany is extremely detrimental. It is obvious that the situation is markedly better abroad, albeit not satisfactory there, either. It would accordingly have been the first task of a publisher intent on promoting writing about cinema belatedly to raise the general level while also plugging existing gaps by commissioning new work. Instead, books are published helter-skelter, in line with an editorial ethic that has it that movie fans here should be glad to have whatever windfalls they happen to pick up.

P.S. Pro domo: when I offered Hanser my history of emigration in the German-speaking film industry for publication by 1976, they responded with an offer of a 1,000 (one thousand) mark advance and a further 500 (five hundred) marks on submission of the manuscript! Try to imagine the art this calls for: delivering, in exchange for such a ludicrous fee, a hunk of baloney turned out fast enough to enable an author to squeeze a month’s rent out of it.

24.

At the age of sixteen, I was “discovered” not just as a “poet” by Hans W. of Vienna and one Dr. Walter Z., a Styrian hack specializing in patriotic schmaltz, but also as a track-and-field hopeful. I was pale and unprepossessing and had no spikes, but I ran the thousand meters in a respectable un-der-three-minutes. I trained indoors all winter and had the feeling that I almost enjoyed it. But, for school-related reasons, I had to opt for either sports or culture. Stupidly, I picked culture. That’s how the whole shit show started.

- 1Julian Volz, “Prolegomena. Straschek 1963 – 74 West Berlin (Filmkritik 212, August 1974)”, Sabzian (2022)

This text was originally published as “Straschek 1963-74 Westberlin” in Filmkritik vol. 8, no. 212 (August 1974), and will be published in 4 parts on Sabzian in the coming months.

Cinematek and the Goethe-Institut Brussels will dedicate a retrospective and an exhibition to Günter Peter Straschek in June 2022.

This project was realised with the support of the Goethe-Institut Brussels.

With thanks to Karin Rausch, Julian Volz and Julia Friedrich and the Museum Ludwig Cologne for providing the english translation.

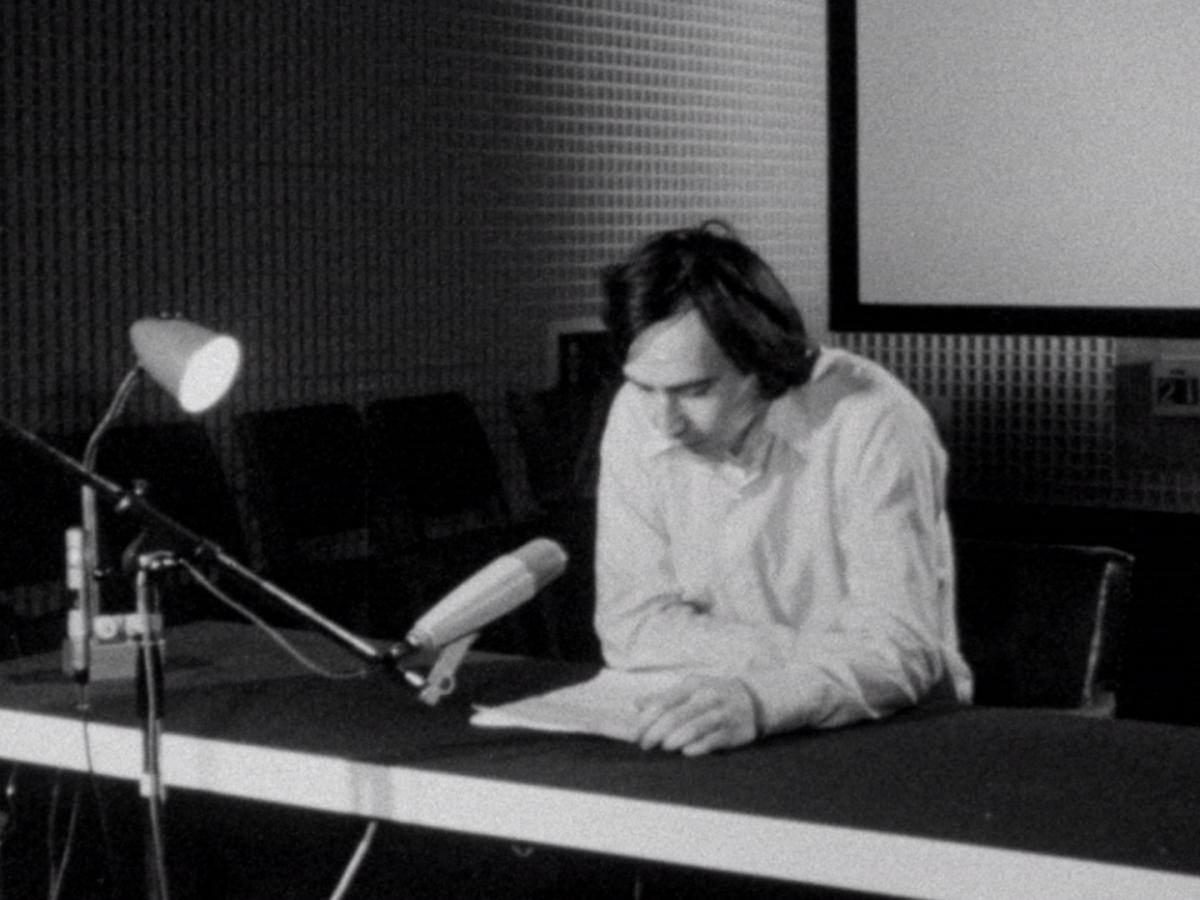

Image (1) Günter Peter Straschek reads aloud a letter from Arnold Schoenberg addressed to Wassily Kandinsky in Einleitung zu Arnold Schoenbergs Begleitmusik zu einer Lichtspielscene (Jean-Marie Straub, 1973)

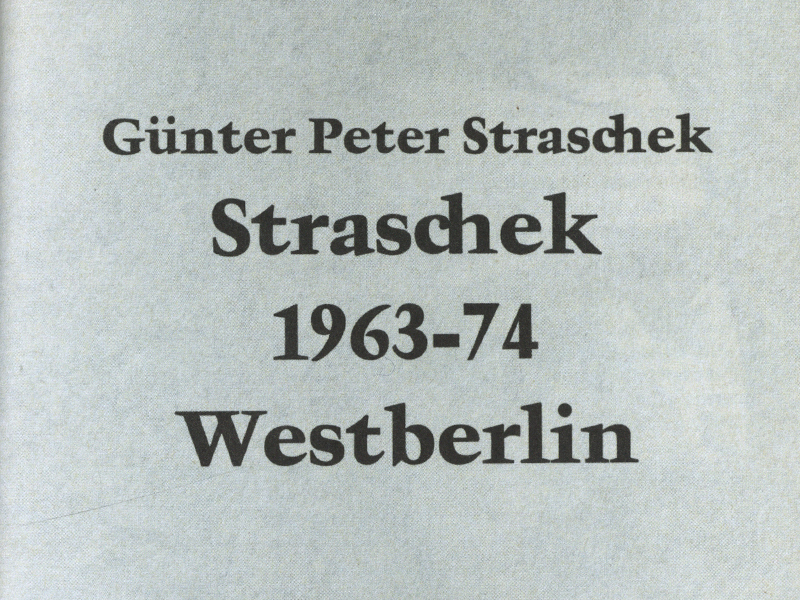

Image (2) Günter Peter Straschek on the cover of Filmkritik vol. 8, no. 212 (August 1974)

Images (3) and (4) from Filmkritik vol. 8, no. 212 (August 1974)

Image (5) “Social responsibility; or, my friends’ cats, entrusted to my care.” Danièle H.’s instructions for Misti in Rome, Fall 1973.