Prolegomena

Straschek 1963 - 74 West Berlin (Filmkritik 212, August 1974)

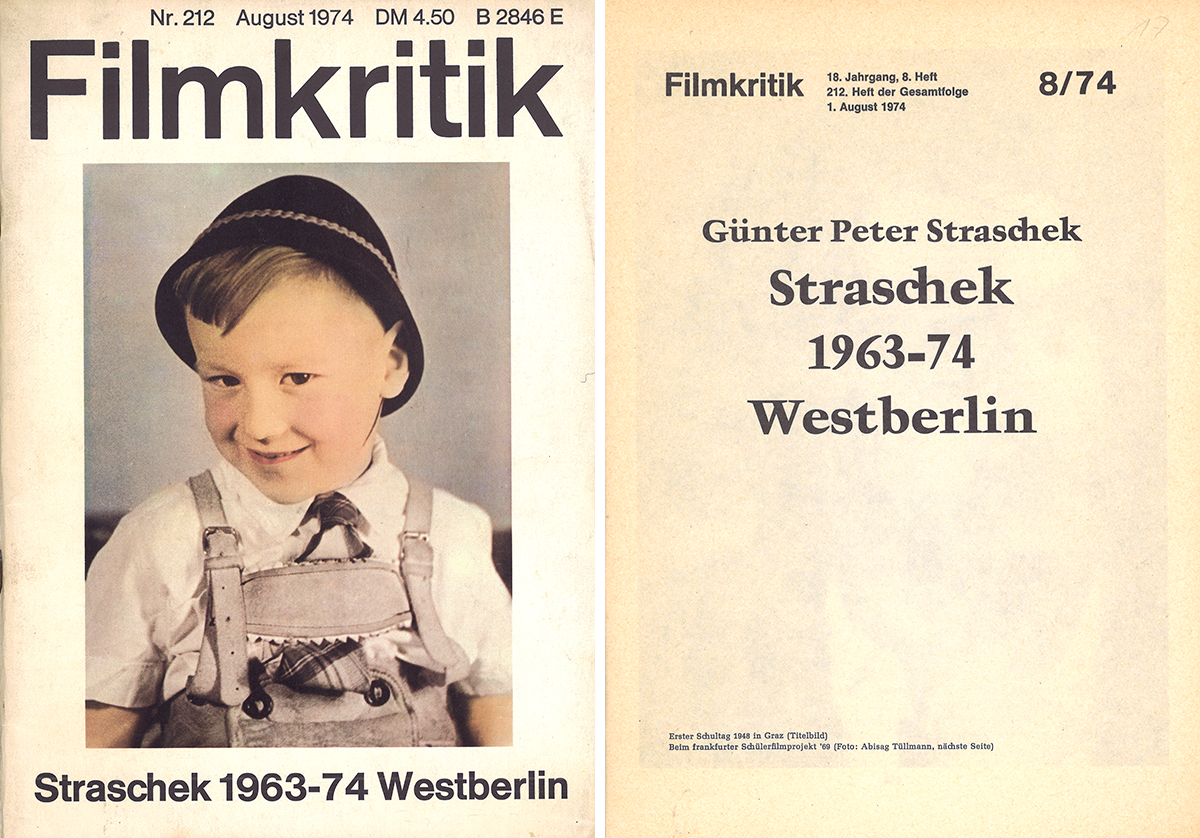

The title of the text “Straschek 1963–74 West Berlin” is as simple as it is informative: it is a subjective, self-reflective insight into Günter Peter Straschek’s eleven years in West Berlin. During this time, he was many things: filmmaker, film historian, film theorist, writer, politically active in the protest movement of 1968 and part of the first generation of students at the Deutsche Film- und Fernsehakademie Berlin [German Film and Television Academy Berlin] (DFFB). Straschek’s fellow students included people like Helke Sander, Harun Farocki, Hartmut Bitomsky, Johannes Beringer and Holger Meins. His essay provides unique access to the film-aesthetic and -theoretical debates and practical-political discussions of a generation of filmmakers who were to fundamentally renew filmmaking in Germany, and whose political and formal experiments made the preceding generation of Oberhausen Manifesto filmmakers look staid. Born in Graz on 23 July 1942, Straschek merged his experiences and interests from his West Berlin period into one condensed virtuoso composition for the magazine Filmkritik. Straschek created a constellation of various text types, such as political-theoretical and film-aesthetic reflections, anecdotes, diary-like entries, letters or even feeding instructions for Danièle Huillet’s cat. It is a text montage that most film-magazine editors today would probably shorten considerably and change formally. The text owes its publication in this form to the spirit of the time, but especially to the editorial guidelines of Filmkritik, which was certainly the most prominent film magazine in the German-speaking world at the time.

Founded in the late 1950s by young students such as Enno Patalas, Wilfried Berghahn and Theodor Kotulla, and directed against the German film criticism and post-Nazi cinema of the time, Filmkritik mainly pursued critique of ideology and an internationalisation of its discourse in the first decade of its existence. In a self-analytical text, Frieda Grafe describes this initial constellation as follows: “The vigour of the early days of Filmkritik came from the adversarial attitude towards the feuilletonistic and ideological drivel that masqueraded as film criticism in Germany.”1 At the end of the 1960s, there was a change of generations at the magazine and the editorial work was henceforth led by a collective, the film critics’ co-operative. From that moment, the magazine stopped being a film magazine oriented towards current cinema events and, instead, published thematic issues devoted entirely to one subject and without any formal guidelines. The issues’ respective guest authors and designers were free from editorial intervention. Only these conditions made it possible for literary and film personalities such as Straschek to cover an entire issue with a thoroughly composed biographical essay.2 In this text, Straschek does not refrain from criticising all kinds of currents in the film and political scene that don’t meet his own advanced ideas. He thereby also covered Enno Patalas and Frieda Grafe, who were after all the most important figures of the founding generation of film critics, under sneering derision, labelling them as plagiarising provincials. He puts forward the following thought experiment: if German television were to discover filmmakers such as John Brahm, Jacques Tourneur or Edgar George Ulmer, it would have to “flip back through the Cahiers du cinéma of a decade ago, and the hour of Enno P. cum spouse sounds – hopping other people’s trains and fobbing himself off in these parts as a locomotive engineer.”3

Having left Austria at the age of nineteen after finishing school, then travelling through Western Europe and the Middle East for a few years, he moved to West Berlin in 1963. As he mentions in Filmkritik, he would have preferred to go to East Berlin but, fortunately for him, the GDR had no interest in a destitute intellectual and filmmaker. In Berlin, he first enrolled in film studies at the Technische Universität and was then, in 1966, accepted into the first class of the DFFB, which had been founded in order to give a fresh impetus to Germany’s fusty film industry. Looking back, Straschek writes the following about the early days at the DFFB:

“Thirty-four students, most having already completed (or abandoned) courses of study in some other field or having various kinds of professional experience, now resolutely awaiting the chance to realize long suppressed ideas, and generally equipped with prior theoretical training and self-confidence; a cowardly and insufficiently qualified teaching staff letting itself be pushed back and forth between the student body and the administration; said administration overtaxed by the difficulties stemming from the academy’s recent foundation; and lastly, the innocent years of the student rebellion = 1966–68, I studied directing at the German Film and Television Academy in Berlin, Inc. (DFFB).”4

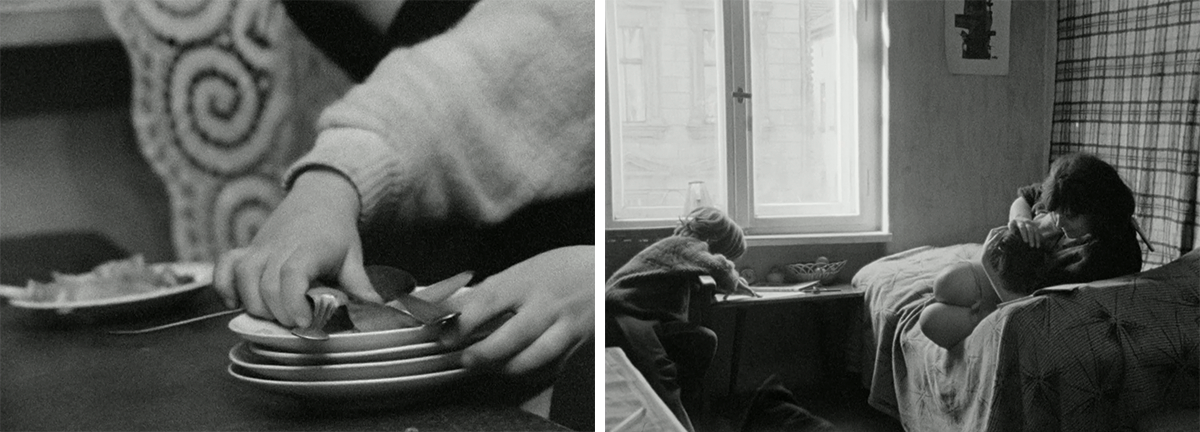

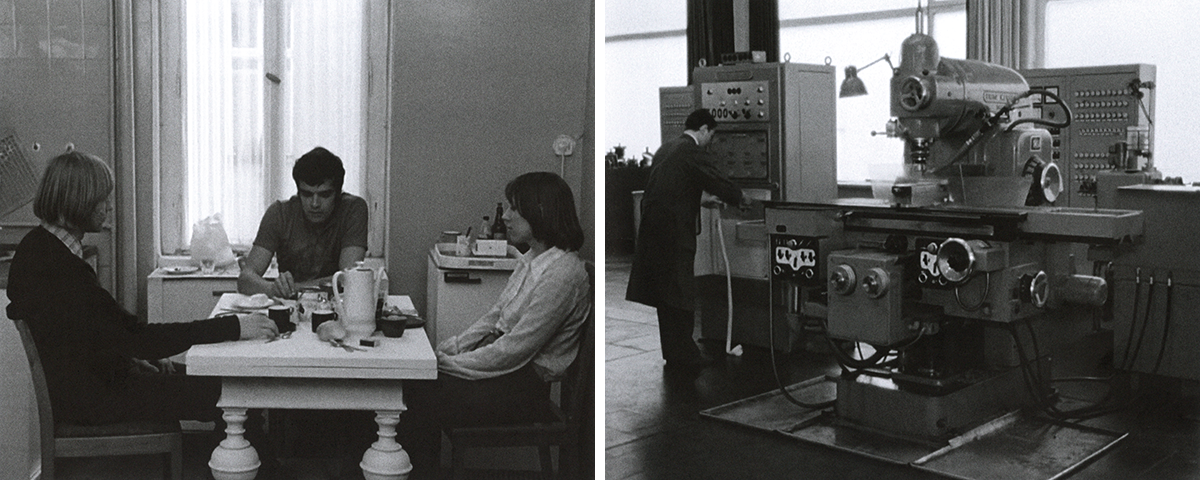

Two of his films were made at the DFFB: Hurra für Frau E. in the first two semesters and Ein Western für den SDS a year later. In between lay a wave of relegations (later reversed), accompanied by the first political struggles at the DFFB and the murder of Benno Ohnsorg by a policeman during a demonstration against the visit of the Shah of Persia on 2 June 1967, which acted as a catalyst for the German student movement, politicising many at a breakneck pace.5 Straschek, however, had already begun to meticulously study the Marxist classics since his arrival in West Berlin. This saved him – as he credits himself – from hasty political actions and opinions. Besides his Marxist studies, Straschek possessed a profound knowledge of the history and aesthetics of film. His Handbuch wider das Kino, begun in 1969 but not published until 1974, is impressive proof of this. In the text in Filmkritik, he self-consciously made public the quarrels with his publisher Suhrkamp that led to the delayed publication of his book.

The combination of his profound knowledge of film and Marxism made Straschek one of the most advanced left-wing filmmakers and theorists of his time, holding the cinematic tastes of most leftists up to mockery (“A few digs at the rich and the cops plus a dash of liberation ideology in the guise of a fuck, plus a couple of red flags – that seems to be enough [...]”) and holding in contempt the aesthetic ideas of the neo-Maoists sprouting up at the time (“Their aesthetics found its culmination in the suggestion to film their May Day march.”) as well as the kitschy self-assurance of revolutionary filmmakers (“I have only to hear phrases like ‘songs are weapons’ or ‘cameras are rifles’ to feel like puking.”). For his own films, on the other hand, he drew heavily on the Brechtian distancing effect and especially on the works of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièlle Huillet,6 with whom he became acquainted in the mid-1960s and later became close friends. Some episodes from this friendship can be found in the text published in Filmkritik.7 As much as he was influenced by their aesthetic approach, he was critical of the “aristocratic” lone-fighter approach of the two, who had no real connections to political movements or other left-wing filmmakers: “S.-H. as model, not as solution.”8 For Straschek, film instead represented a special medium of politically practical labour. One result of his reflections on socialist film work was the so-called “target group films”, which aimed to develop the political consciousness of specific groups of the population, overcoming the conventional division of labour in filmmaking:

“To do socialist film work means: to advance both the practical and theoretical work of revolutionary associations under different, that is, generally anti-capitalist forms of production and distribution, with special regard for the medium of the audio-visual (film).”9

For his work with the student target group, he moved to Frankfurt am Main in 1968 – he had just been expelled from the DFFB for the second time because of his political activities – together with his closest friend, Holger Meins. Unlike Straschek, Meins was still officially a student at the DFFB and was able to borrow the technical equipment for the project from the academy. As Straschek reports, the work began with a lot of enthusiasm, but it came to a standstill when the collective montage should have begun. After the end of the project in Frankfurt, the two went their own separate ways. Meins joined the Rote Arme Fraktion (RAF) urban guerilla in 1970, participated in attacks on US military installations in the FRG in the context of the Vietnam War and was ultimately arrested in 1972. He died in prison in 1974 after a long hunger strike.10 In a letter to Huillet–Straub a few days after Meins’s arrest, Straschek wrote: “Of course I didn’t get along with H.M. anymore (I’m not against violence, quite on the contrary: [...] but I’m for organised and against individualist-anarchist violence), but we were together for two years and I just liked him.”11

After the failed project in Frankfurt, Straschek started working on his last film, Zum Begriff des “kritischen Kommunismus” bei Antonio Labriola (1843-1904). This film, like the two previous ones, also deals with the topic of women and socialism (and the relationship between intellectuals and workers). It is astonishing how early Straschek recognised the relevance of feminism and processed it cinematically. For the theoreticians and chief cadres of the Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund (SDS), the most important organisation of the German student movement, of which Straschek was also part, ignored the topic persistently. Even the interventions of the women’s movement during the SDS delegates’ conference in 1969, instigated by Straschek’s fellow student Helke Sander,12 among others, did not lead to any serious discussion of the feminist criticism of the SDS’s policies.13 The Filmkritik text makes clear why the Labriola film was Straschek’s last. His revolutionary film-aesthetical and technically demanding notion of film work did not match the views of most producers, film funds and TV editors, which is why he had to realise the Labriola film in the most precarious conditions – only Alexander Kluge, Jean-Marie Straub and his former fellow student Johannes Beringer, who had just sued the DFFB for being expelled and received a compensation, contributed some money to the film project. Straschek writes: “I’m no longer willing to shoot a film under similarly ‘independent’ conditions, with money scraped up here and there.”14 Consequently, this film marks the end of Straschek as a filmmaker in the strict sense.15 In Filmkritik, Straschek describes a few anecdotes of failed projects for television.

From the beginning of the 1970s, he turned primarily to publishing and especially to a project that would accompany him until the end of his life in 2009: the research into the “fate” of filmmakers that had been expelled from Nazi Germany. In doing so, he not only dealt with the exile of renowned directors such as Fritz Lang, but with anyone who had been part of the German film industry of the 1920s and 30s. It is true pioneering work because nobody else in post-fascist Germany was interested in these anti-fascist and/or Jewish emigrants. Fortunately, this project provided him with a first and last engagement for television. An editorial department of the WDR, headed by Werner Dütsch, commissioned him to produce a five-part series that was broadcast on German television in 1975. Some anecdotes about the work on this series can be found in the Filmkritik text. Straschek continued his research unabated after the end of the series. In total, he interviewed 2800 people working in the film industry who were expelled from Nazi Germany. A comprehensive publication was planned, which was to appear in the 1980s. Unfortunately, that didn’t happen. The research on emigration in the film industry opened up so many paths for him that he, who tackled everything with the utmost precision and perfectionism, was never able to complete the project. This, too, is highly regrettable.

- 1Frieda Grafe, “Zum Selbstverständnis der Filmkritik”, in: Filmkritik 118 (October 1966). For more information about Frieda Grafe’s texts in Filmkritik, see: Gerard-Jan Claes, “De algemene kleur van films. Over Frieda Grafes filmkritiek”, Sabzian (2020).

- 2For more information about Filmkritik and its development qua content and form, see the following two very informative texts: Markus Nechleba, “50 Jahre Filmkritik”, Programmheft 13 (Filmmuseum München, 2007/2008), 24–27.

Volker Pantenburg, “Film-Praxis und Text-Praxis. Harun Farocki und die Filmkritik”, in: Harun Farocki, Ich habe genug! Texte 1976-1985, edited by Volker Pantenburg (Cologne, 2019), 449-465.

This paragraph is largely based on these two articles. - 3Günter Peter Straschek, “Straschek 1963–74 Westberlin”, Filmkritik 212 (August 1974), 352.

- 4Ibid., 357.

- 5For an account of the political struggles at the DFFB, see: Fabian Tietke, “Dies- und jenseits der Bilder – Film und Politik an der dffb 1966–1995”, Deutsche Kinematek.

The article includes numerous films made at the DFFB during this period.

Jean-Gabriel Périot’s film Une jeunesse allemande (F, 2015, 93 min.) provides an impressive archive-based insight into the political atmosphere at the DFFB and in West Berlin at that time. - 6In the catalogue of the exhibition Günter Peter Straschek: Emigration – Film –Politics, the curator Julia Friedrich impressively elaborates on these influences. Cf. Julia Friedrich, “Introduction”, in: Julia Friedrich (ed.), Günter Peter Straschek: Emigration – Film – Politics (Cologne, 2018), 35.

- 7Straschek even has a role in Straub–Huillet’s film Einleitung zu Arnold Schoenbergs Begleitmusik zu einer Lichtspielscene (FRG, 1972, 16 min.). He can be seen reading a letter from Arnold Schönberg to Kandinsky. Peter Nestler also appears in the film alongside him. Nestler in turn reads a passage by Brecht.

- 8Straschek, op. cit., 354.

- 9Günter Peter Straschek, “Gegen Moralismus, für Konsum!”, Film 7, no. 3 (March 1969), 7.

- 10In her film Es stirbt allerdings ein jeder, fragt sich nur wie und wie Du gelebt hast (Holger Meins) (FRG, 1976, 60 min.), the filmmaker Renate Sami lets old companions of Meins’s have their say, sensitively tracing the question of how this tragedy could have happened. She spoke with Straschek too. Among other things, he talks about their joint work on the student film project in Frankfurt.

- 11Letter from Straschek to Straub–Huillet, 4 June 1972, facsimile in: Julia Friedrich (ed.), Günter Peter Straschek: Emigration – Film – Politics (Cologne, 2018), 303.

- 12Sander would later deal with these discussions in her film Der subjektive Faktor (FRG, 1981, 138 min.).

- 13I dealt with the ignorance of the SDS chiefs towards the demands and topics of the newly emerging second women’s movement in detail in the following essay: Julian Volz, “Das ‘historisch neue Vernunftprinzip der Emanzipation’. Über Krahl, Marcuse und die neue Frauenbewegung”, in: Meike Gerber, Emanuel Kapfinger, Julian Volz (eds.), Für Hans-Jürgen Krahl. Beiträge zu seinem antiautoritären Marxismus (Berlin & Vienna, 2022), 198–225.

- 14Straschek, op. cit., 367.

- 15Stefan Ripplinger correctly notes that “few things in the history of recent German cinema [are] to be regretted as much as this situation”. Stefan Ripplinger, “Fräulein vs. Funktionäre. Günter Peter Strascheks Ein Western für den SDS (1967/1968)”, in: Julia Friedrich (ed.), Ein Western for the SDS, Günter Peter Straschek (Cologne, 2019), 11.

For further reading:

Günter Peter Straschek, Handbuch wider das Kino, Frankfurt am Main, 1974. (Available second-hand.)

Julia Friedrich (ed.), Günter Peter Straschek: Emigration – Film – Politics, Cologne, 2018. (Bilingual catalogue, in German and English, of the exhibition of the same name.)

Julia Friedrich (ed.), Ein Western für den SDS, Günter Peter Straschek, Cologne, 2019. (With English supplement.)

This article is an introduction to “Straschek 1963-74, West Berlin”, and was realised with the support of the Goethe-Institut Brussels.

Cinematek and the Goethe-Institut Brussels will dedicate a retrospective and an exhibition to Günter Peter Straschek in June 2022.

Image (1) Cover Filmkritik vol. 8, no. 212 (August 1974)

Images (2) from Hurra für Frau E. (Günter Peter Straschek, 1967)

Images (3) from Ein Western für den SDS (Günter Peter Straschek, 1967-68)

Images (4) from Zum Begriff des “kritischen Kommunismus” bei Antonio Labriola (1843-1904) (Günter Peter Straschek, 1970)