Corneille-Brecht, or Rome, Unique Object of My Resentment (2009, 26 min. 43 sec.)

“I hope you will be put on trial.” – Tomas Young, a dying Iraq war veteran

In leaps of physical color, Cornelia Geiser recites verses from two of Pierre Corneille’s Roman plays, Horace and Othon, followed by verses from Bertolt Brecht’s 1939 radio play The Trial of Lucullus, a powerful recitative on war crimes in fourteen short pieces (never broadcast; later turned into an opera by Brecht and Paul Dessau in East Germany).

In the Lucullus play, which Brecht said at the time “more or less reaches the limit of what can be said” in oppressive times, a Roman General is summoned to the netherworld to stand trial for the crimes and sufferings he has inflicted on the common people and slaves. A giant frieze is hauled in and analyzed for the variety of life seen plundered there.

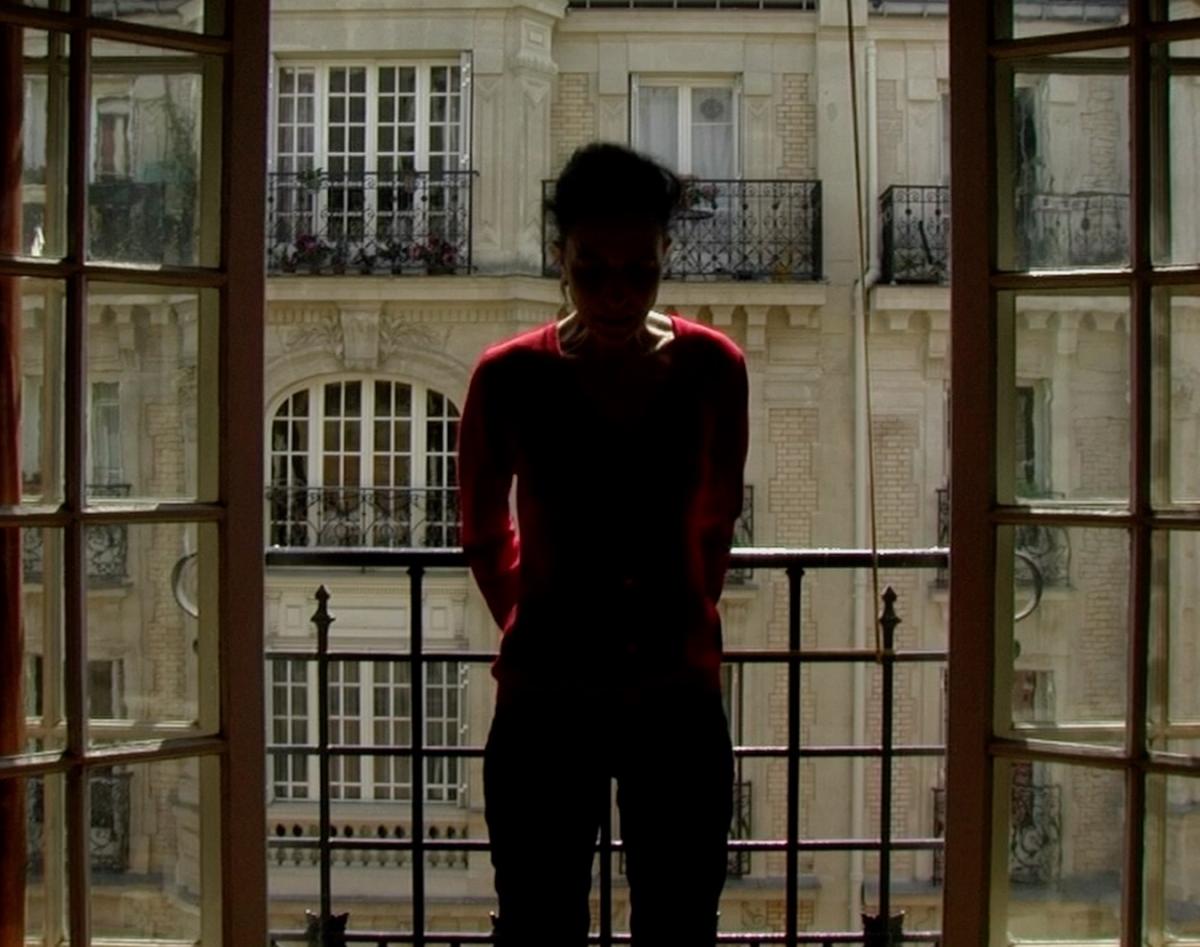

Across centuries of Western civilization, Straub and Geiser bridge these texts of different epochs and – in two corners of a small Parisian apartment – confront the barbarous rulers of ancient Rome, the kings of 17th century France, the fascists of Europe in the 1930s and 1940s, and, by implication, those in power today.

Cumulatively, it is not the rulers who are the main characters here but the collective judgment of the oppressed upon the oppressor.

“Maybe it’s not even a movie,” Straub wondered aloud during a post-screening talk on Corneille-Brecht. Indeed, this movie is “just” a woman reading a text frontally to the camera in the same corner of Straub’s Parisian apartment (once Huillet’s mother’s) that is the site of many of the late videos, and this is the first use. But the words and their drama and intonation invoke massive friezes, ultimate judgments, conflagrations, the ‘collective hate’ of “Rome, l’unique objet de mon ressentiment,” (Corneille’s French will ring in the ears of anyone who sees all three versions of the film in succession, as intended), then goes down even deeper (with the Brecht), down to a Hades where a trial for war crimes is taking place against an imperialist, perhaps the same imperialist, perhaps any imperialist. It would be foolish to call this picture minimalist, for even if its rich sound (a baby cries on the line “…the collective hate” in version A) were turned off, one could be fascinated by the violent changes of color in wardrobe and sunlight, here effected by jump cuts – yet another cinematographic vein Straub has tapped for both sudden and gradual excitation. Fascination, magic, and belief are part of Huillet/Straub’s cinema, too, occurring amid their total opposite – analysis, critical faculty, errant thought – and back again. One may feel upon leaving the theater a sharpening of the senses.

Image from Corneille-Brecht ou Rome l’unique objet de mon ressentiment (Cornelia Geiser & Jean-Marie Straub, 2009)

With thanks to Oscar Pedersen, Viktor Retoft and Balthazar.

This article was originally published in Balthazar no. 9, 2023, dedicated to the work of Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub.