A musical comedy set in a shopping mall, between Lili's hairdressing salon, the Schwartz family's ready-to-wear boutique and Sylvie's bistro. Employees and customers cross paths, meet each other and dream of love, whether compromised, epistolary or impossible. They talk about it, sing about it and dance about it, punctuated by the chorus of shampoo girls.

EN

Nicole Brenez: Did you keep any traces from Levinas’ seminars?

Chantal Akerman: No, I didn’t take notes and I forgot everything after my first breakdown. Since then, my memory’s been worse. It was a real disaster, just before Golden Eighties, which hadn’t been made as I wanted.

I remember just how out of place and explosive it seemed in the landscape of the time; nobody was expecting such a joyous, colourful musical. That kind of exhilaration ran completely against the dominant taste in auteur films of the ‘80s.

They kept wanting me to remake Jeanne Dielman, but I wanted to spurn everything – spurn my father’s name, not repeat myself. I did a number of trial runs for it, and Les Années 80 (The ‘80s) and the others are possibly more joyous than the final film, which suffered from a lack of resources, among other reasons. In any case, I was very happy to write the songs. [She sings]

Nicole Brenez1

“Golden Eighties may not seem much like a teen movie to some, but it is from this contemporary genre, more than from old musicals, that Akerman here draws her bemused tone, and her cultural purview. Her film encircles a post-feminist (and post-political) space of endless consumption, glitzy all-pervasive commodification of emotion, showbiz femininity, regressive longings for the perfect romance, a certain delicate kind of camp sensibility. And who can say to what extent this is Akerman’s own space, her own sensibility? Is there really a critical, ironic sting to this tale (above all else), or rather an affectionate accommodation to a restricted notion of everydayness in the eighties – hardly golden, yet not, it seems, so harsh, either? For at least, in this world, love is everywhere (a Demy theme, announced from the second shot of a woman kissing two men), a passionate force circulating almost independently of the people it moves and tangles.

As a minute experiment with musical image-and-sound form, Golden Eighties deserves a long and close commentary. Let me merely suggest, for those with good ears, some great things to listen for – things which are not gags or even jokes but (as in Jacques Tati’s intricately post-dubbed cinematic universes) maddeningly infectious touches: the constant clackety-clack footsteps; the signifying of boutique muzak by a drum machine loop that gets busier each time it reappears; the deft conversion of an air-conditioner’s ‘whoosh’ or a pesky dress zipper’s noise into synthesized, rhythmic elements of the music; and the ever changing acoustics of voice and speech – spoken, sung, whispered, solo, en masse, with and without echo. One has the sense of hearing a sound ‘mix’, complete with stops, starts, modulations, tryouts ... laboratory experiments of all kinds.”

Adrian Martin2

“Akerman presents us a network narrative without a clear point of view belonging to any one particular character, following the developments in the ever-changing relationships between her ensemble cast. Akerman wouldn’t be Akerman if she hadn’t staged this very precisely. These bodies navigate the space they dwell in with a remarkable fluidity of movement. With the exception of Eli and Monsieur Jean, the shopping mall is their whole world and therefore they know it intimately. When they burst into song they not only sing for us, but also for the people around them. What is really put on display here are the characters themselves. But the act of window-shopping (like the act of looking at the cinema screen for that matter) doesn’t give you what you desire. It can only show you how to desire. Everyone in the film moves around each other but, like in the opening shot, nobody connects. There is no real exchange. There’s no forming of the couple like in The Band Wagon, where Fred Astaire and Cyd Charisse’s characters can’t stand each other at first (because they dance different styles) but still seek to understand one another and finally, while walking in Central Park, learn how to move their bodies in harmony, dance step by dance step.”

Alain Tijong3

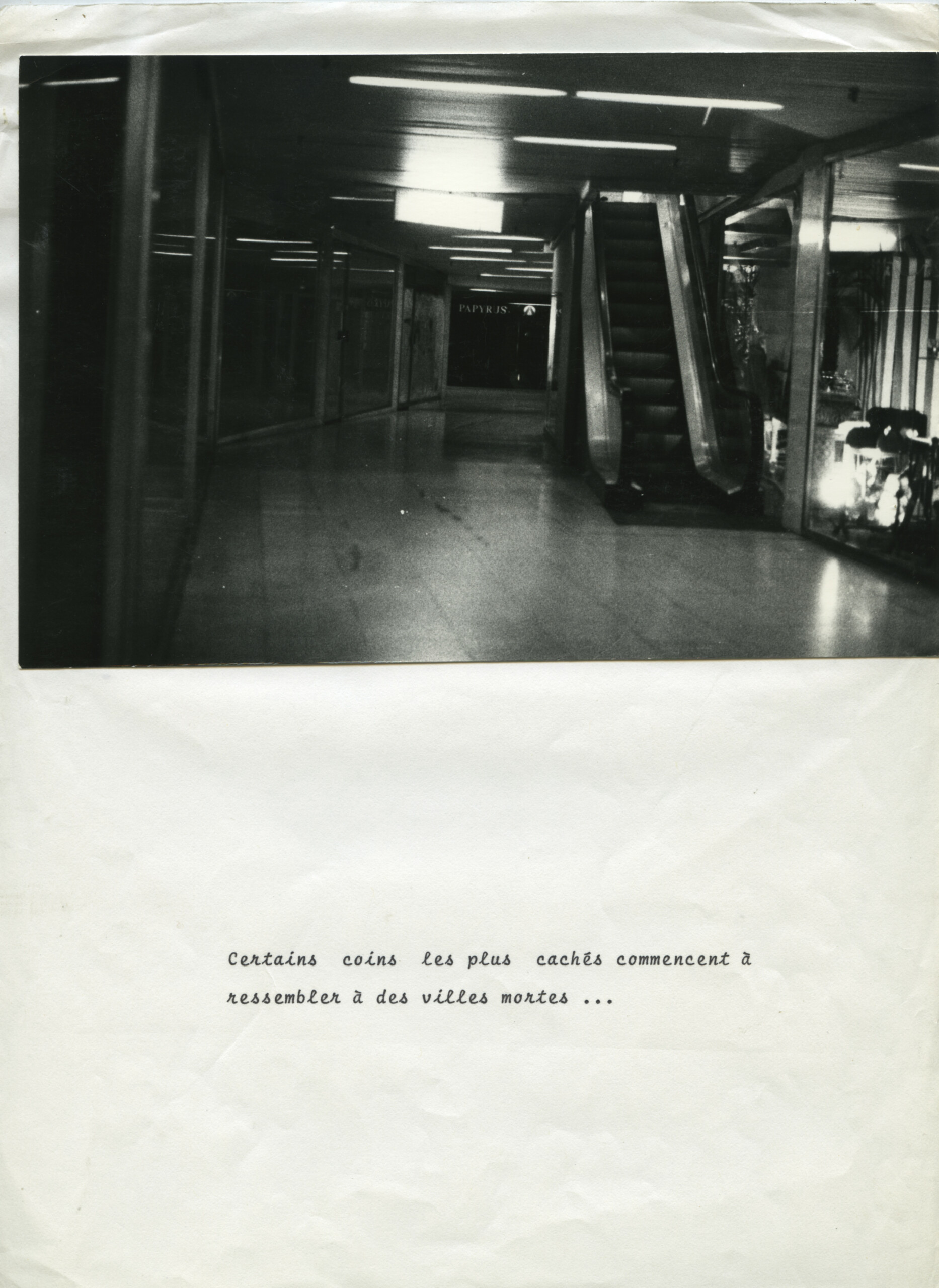

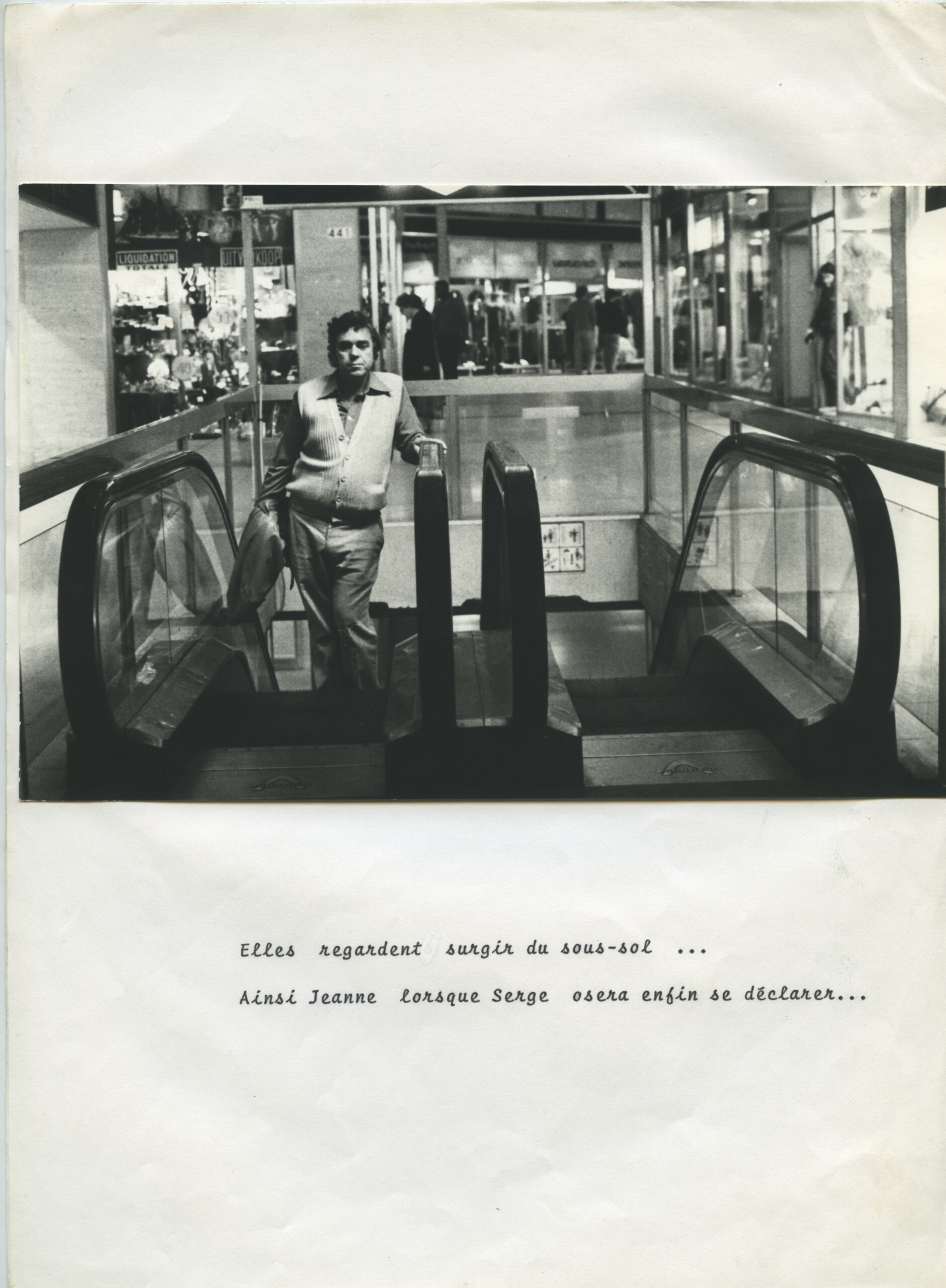

“The location itself is the point of departure. For everything. A shopping mall in Europe City. More precisely, the Galerie de la Toison d'Or. A space which makes everyone in it both a spectator and an actor despite himself: the ideal setting for a musical. Everything is performance. Show business.”

Chantal Akerman4

- 1Nicole Brenez, “Chantal Akerman. The Pajama Interview,” LOLA Journal, translated by David Phelps, 2012.

- 2Adrian Martin, ‘Golden Eighties,’ Film Critic: Adrian Martin, July 1989.

- 3Alain Tijong, "Shop Windows of Desire 2 – Golden Eighties," Cinea, 23 August 2016.

- 4Chantal Akerman, "Location scouting photos," Fondation Chantal Akerman.

NL

“Aanvankelijk zin om een komedie te maken.

Een komedie over de liefde... en de handel.

Burlesk; teder, waanzinnig.

Vervolgens was één plaats het uitgangspunt van alles.

Een plaats die ik goed ken omdat ik er verscheidene malen als verkoopster heb gewerkt.

Een winkelgalerij, om precies te zijn de ‘Galerie de la Toison d’Or’ in Brussel.

Een architektoniese ruimte die de plaats zal worden van één of meer komiese verwikkelingen, waar een sentimentele ruimte zou kunnen ontstaan, en waar achter de komedie, en met de komedie, het geweld zich zou kunnen aftekenen, een dof, alledaags geweld.

Chantal Akerman1

- 1Chantal Akerman, “La galerie,” Versus, vertaald door Jack Post, oorspronkelijk verschenen in Ateliers des Arts, Brussel 1982, 113-118.