A retired jewel thief sets out to prove his innocence after being suspected of returning to his former occupation.

EN

“Susan Green: But then friction began to develop between you and Hitchcock. Did it start while you were in the south of France shooting To Catch a Thief?

John Michael Hayes: I don't recall any real problems then. I think the worst fight we ever had was over the ending of To Catch a Thief. We had different ideas. I wrote twenty-seven different endings and still don't like the one that was used. We had a couple of slam-bang script fights. Still, we got along fine until I got too much press. When we went to Paris for the premiere of To Catch a Thief, I was getting mentioned everywhere – they value writers in Paris – so I was promptly banned from all public relations events. If I was mentioned in the fourth paragraph of a story, that was okay but not in the first or second. I was becoming known for my dialogue and characterizations. They even talked about "the Hitchcock-Hayes fall schedule" in either Variety or the Hollywood Reporter.”

Susan Green1

“We met the first time at the flower market in Nice. They were shooting a scuffle. Cary Grant was fighting with two or three ruffians and rolling on the ground under some pink flowers. I had been watching for a good hour, during which time Hitchcock did not have to intervene more than twice; settled in his armchair, he gave the impression of being prodigiously bored and of musing about something completely different. The assistants, however, were handling the scene, and Cary Grant himself was explaining Nice police judo techniques to his partners with admirable precision. The sequence was repeated three or four times in my presence before being judged satisfactory, after which they were to prepare to shoot the following sequence – an insert in close-up of Cary Grant’s head under an avalanche of pink flowers. It was during this pause that Paul Feyder, French first assistant on the film, presented me to Hitchcock. Our conversation lasted fifty or sixty minutes (there were retakes) during which time Hitchcock did no more than throw one or two quick glances at what was going on. When I saw him finally get up and go over for an earnest talk with the star and the assistants, I assumed that here at last was a matter of some delicate adjustment of the mise-en-scène; a minute later he came towards me shaking his head, pointing to his wristwatch, and I thought he was trying to tell me that there was no longer enough light for color – the sun being quite low. But he quickly disabused me of that idea with a very British smile: ‘Oh! No, the light is excellent, but Mister Cary Grant’s contract calls for stopping at six o’clock; it is six o’clock exactly, so we will retake this sequence tomorrow.’ In the course of that first interview I had time to pose nearly all of the questions I had had in mind, but the answers had been so disconcerting that, full of caution, I decided to use a counterinterrogation as a control for some of the most delicate points. Most gracefully, Hitchcock devoted another hour to me several days later in a quiet corner of the Carlton in Cannes. What follows comes out of these two interviews without, in general, any distinction between what was in the first or the second.

[...]

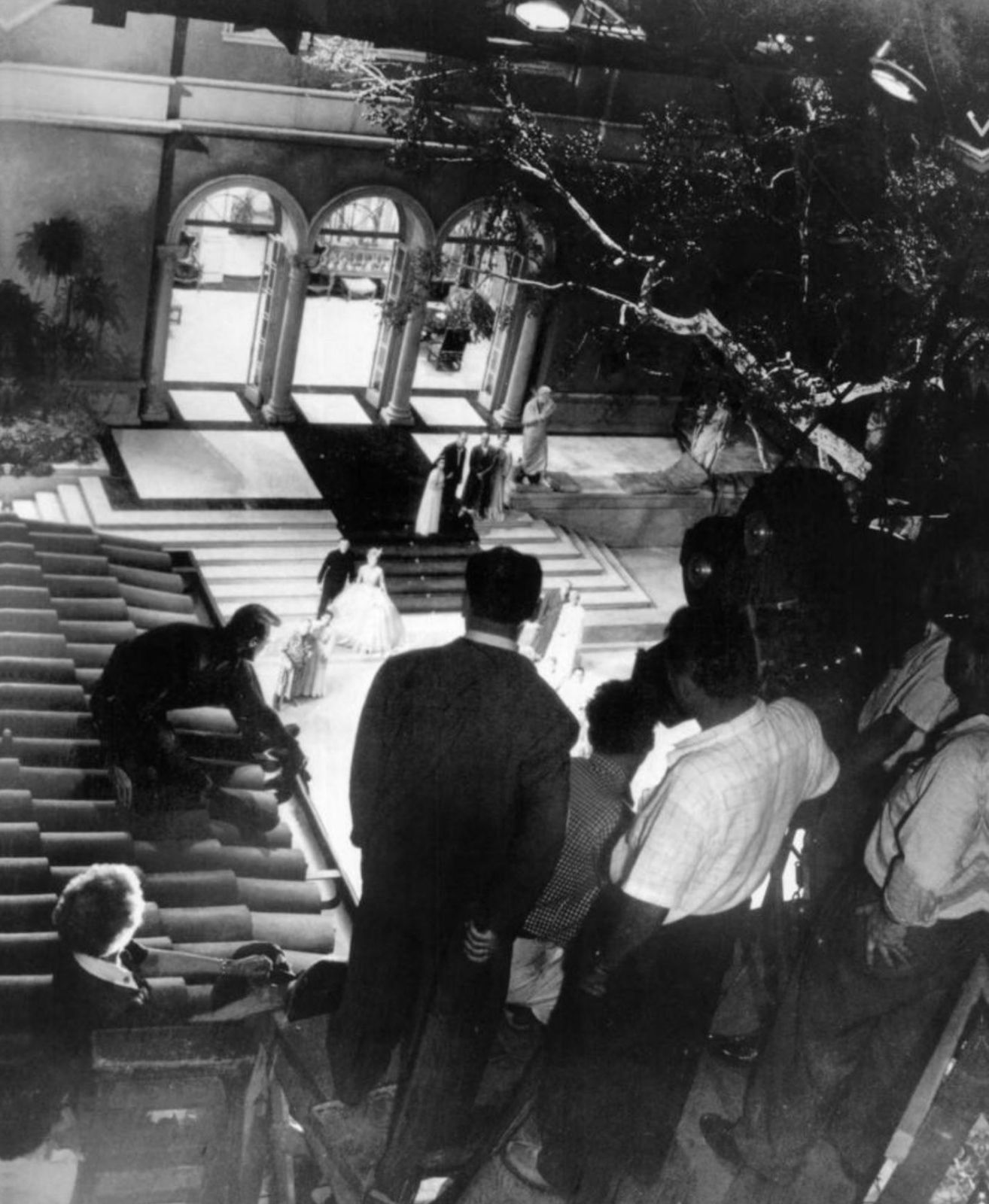

One more question to get off my conscience, the answer to which is easy to predict: Does he use any improvisation on the set? – None at all; he had To Catch a Thief in his mind, complete, for two months. That is why I saw him so relaxed while ‘working.’ For the rest, he added with an amiable smile, lifting the siege, how would he have been able to devote a whole hour to me right in the middle of shooting if he had to think about his film at the same time?”

André Bazin2

“In a striking sequence that relies heavily on rear projection, John (Cary Grant) and Francie (Grace Kelly) drive along the Riviera coastline, making hairpin turns and sparring verbally while being tailed by police. Edited together with location shots completed by the second unit, the shot cuts to the foreground actors, sitting in a glossy, bluish-green car, in very sharp focus. Rather hard, shiny lighting effects sculpt the figures of the actors in richly colored Vista Vision Technicolor, especially noticeable in Francie's shimmering highlighted blonde hair and bright salmon-pink dress and John's deeply tanned, somewhat leathery skin. The background plates, by contrast, are faded and smudged, which is different from simply being out of focus. The color of the plates is of a markedly more muddy hue and cool blue tone than the foreground. Also, there is a subtle difference in the way the eye perceives the speed of the car and the speed of the background. These differences persist despite the large-format Vista Vision system, used to film both the foreground and background plates; at the time this system was marketed as providing the most saturated color possible. The effect of the contrast of foreground and background, common in such scenes (and not solely attributable to Hitchcock's intention), is like a shallow stereoscopic effect, and is noticeable as a composite, however subtly. In other words, the foreground makes one flat plane, and the background another flat plane; there is no fully convincing illusion of a whole. Color, large-format film stock, and the popularity of location shooting in part initiated by films like To Catch a Thief pointed up the visual disadvantages of rear projection and gave technicians headaches for the next two decades.”

François Truffaut: To Catch a Thief was the first film you shot on location in France. What do you think of the picture on the whole?

Alfred Hitchcock: It was a lightweight story.

Truffaut: Along the lines of the Arsene Lupin stories. Cary Grant played ‘The Cat,’ a former high-class American thief who has retired on the Côte d’Azur. When the area is hit by a wave of jewel robberies, he is the logical suspect, both because of his police record and his expert skills. To resume his peaceful existence, he uses these skills to conduct his own investigation. Along the way he finds love, in the person of Grace Kelly, and in the end, it turns out that the guilty party is a ‘she-cat.’

Hitchcock: It wasn't meant to be taken seriously. The only interesting footnote I can add is that since I hate royal-blue skies, I tried to get rid of the Technicolor blue for the night scenes. So we shot with a green filter to get the dark slate blue, the real color of night, but it still didn't come out as I wanted it.

Truffaut: Like several of the others, the plot hinges around a transference of guilt, with the difference being that here the villain turns out to be a girl.

Hitchcock: Brigitte Auber played that role. I had seen a Julien Duvivier picture called Sous Ie Ciel de Paris in which she played a country girl who'd come to live in the city. I chose her because the personage had to be sturdy enough to climb all over the villa roofs. At the time, I wasn't aware that between films Brigitte Auber worked as an acrobat. That turned out to be a happy coincidence.

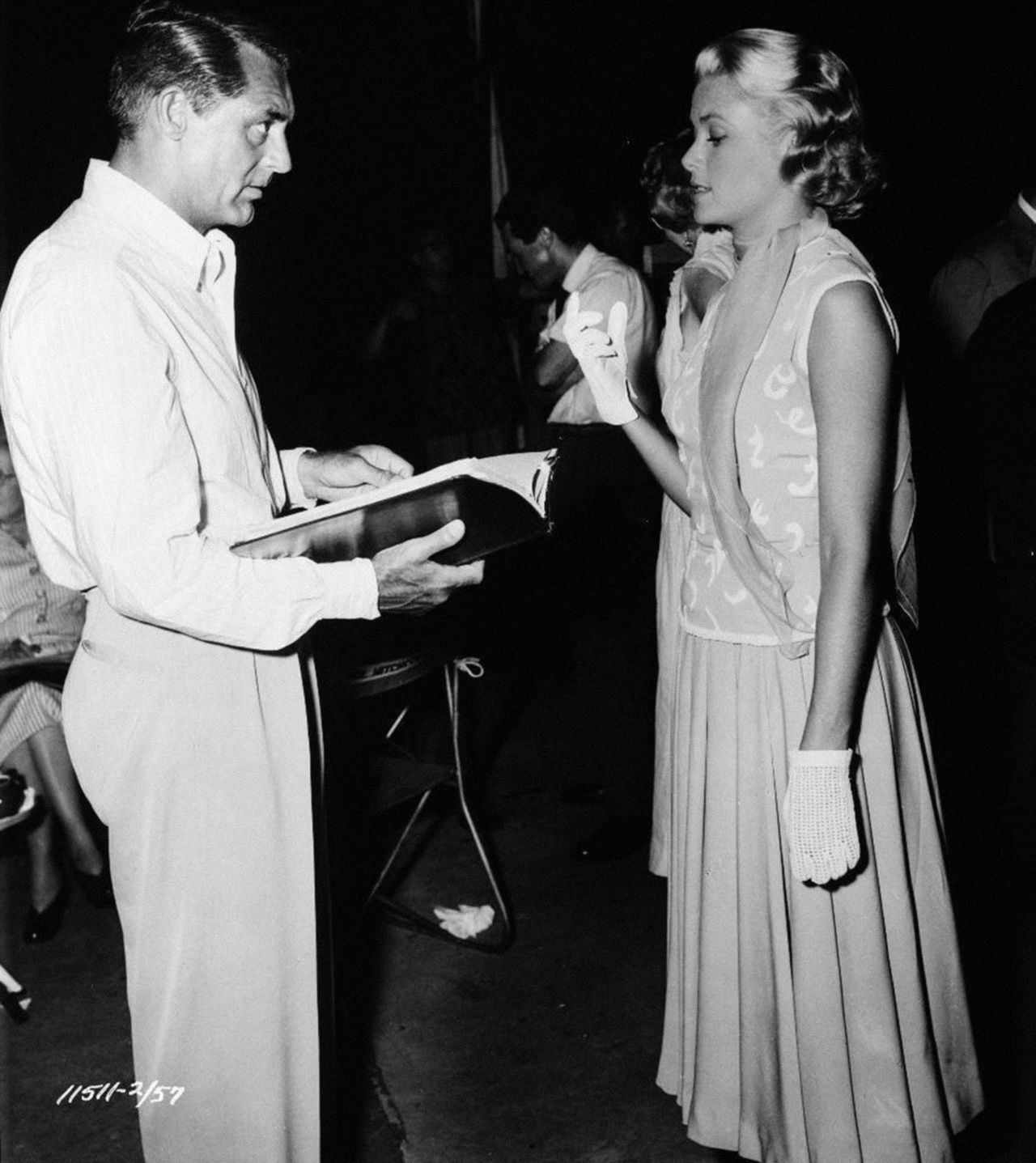

Truffaut: This is the picture that aroused the press’s interest in your concept of movie heroines. You stated several times that Grace Kelly especially appealed to you because her sex appeal is "indirect."

Hitchcock: Sex on the screen should be suspenseful, I feel. If sex is too blatant or obvious, there's no suspense. You know why I favor sophisticated blondes in my films? We're after the drawing-room type, the real ladies, who become whores once they're in the bedroom. Poor Marilyn Monroe had sex written all over her face, and Brigitte Bardot isn't very subtle either.

François Truffaut in conversation with Alfred Hitchcock4

- 1Susan Green, "John Michael Hayes: Qué Sera, Sera," Backstory 3: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 60s. (University of California Press, 1997), 183. Edited by Patrick McGilligan.

- 2André Bazin, “Hitchcock contre Hitchcock,” Cahiers du Cinéma 7, nr. 39, 1 October 1954, 25.

- 3Julie Turnock, “The Screen on the Set: The Problem of Classical-Studio Rear Projection.” Cinema Journal 51, no. 2, 2012, 157–62.

- 4François Truffaut, Alfred Hitchcock, Hitchcock/Truffaut, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1967), 143-156. Edited by Helen G. Scott.