Political Cinema Today

The New Exigencies: For a Republic of Images

Cinema and World

“World Cinema”, to a French eye, is a very welcoming notion that could mean several different, even contradictory things. Among these, I will evoke three meanings:

1. Because of its predecessor World Music, which means the ethnic music re-arranged with electronic instruments to please Western consumers, World Cinema could function as a seductive formula for acculturation – after exploiting gold, diamond and every other kind of material resource, now the Western world is exploiting the immaterial patrimony of the rest of the world, including, of course, its own inner colonies.

2. In a much more objective, generous sense, World Cinema can mean “every kind of cinema that appears in the world” – as Philippe Grandrieux might have put it, according to his historical TV experiment of 1987, The World is Everything That Happens (Le monde est tout ce qui arrive). The syntagm World Cinema helps to identify and evaluate non-dominant cinemas all over the planet. This is the opposite of the previous meaning: World Cinema as opposed to globalised cinema, with a hidden but obvious “s” at the end of Cinema.

3. In a polemical and radical sense – conceptual rather than geographical – World Cinema means the cinema in relationship to the world, cinema in its ability to conceive and reshape the world, as opposed to the “fantasy cinema” that forgets, often hides and sometimes betrays realities.

Serge Daney once proposed a beautiful formula which was an emblem of the second and third meanings above: “Real cinema is made to give the news from where you are” (“Le cinéma est fait pour donner des nouvelles”). So it was important to defend, for example, Lino Brocka – because he was sending news from the Philippines. However, what Daney did not write is that cinema is also important in a non-identitarian, non-national way: to take news from someone (“prendre des nouvelles de quelqu’un”). That is, not thinking and speaking about oneself, who, where and how someone is – but also, to go out from oneself and think of others, especially when they are in danger or in pain.

Once, for example, in Spain in 1936, this move, this gesture was named internationalism – and this old word, devalued by the history of state communisms, still carries some important values that can be used as tools against not only globalised cinema, but also the nation, the communitarianism, the processes of identifications imposed by geography, history and administration – not by an existential, singular, free choice.

A classic example of visual internationalism has, until now, existed in none of the histories of cinema. Le Glas (The Bell Rang for the Dead, 5 minutes) was made by René Vautier in 1964, under the pseudonym of Ferid Dendeni, which signifies “man of Denden”. Denden was the prison, in Tunisia, in which the filmmaker was imprisoned from the end of 1958 to the start of 1960. The narration is by Djibril Diop Mambéty, with music by the Black Panthers. The film was made with the ZAPU (Revolutionary African Party for Unity) to denounce the hanging of three African revolutionaries in Salisbury in South Africa. The film was at first banned in France, then passed in 1965 because it had been authorised in England.

I wish to question what could be an internationalism for today, in the field of cinema – a critical internationalism that defies the powers of state, nation, administration and global economy. Almost all the examples I will cite are provided by filmmakers who are trying to help, through images, people other than their own. Thanks to the films themselves, it seems possible to consider, even very briefly, new proposals concerning the conception of history; the conception of the history of cinema; of an oeuvre; of the filmmaker; of political forms; of curating; and, finally, of spectatorship.

But the main issue here, the main contemporary event, is the suppression of the “division of labour” (la division du travail). Today, anyone has the technical possibility to become a producer of images, a film critic, a curator, even a teacher of cinema. And that is the most beautiful and fertile dimension of cinema: no longer a matter of experts or of specialised activities, it has become, simply, different gestures that the same person can accomplish during a single day: film something, post it on a website, present, discuss, defend it, and comment on other images. Whatever the quality or the tastes, these are now daily gestures for a new generation all over the world.

Let look at a first dimension of this: a new conception of history. The visual laboratory will be X+, an experimental film by Marylène Negro from 2010 (which exists in two versions, of 69 and 112 minutes)

Which History Do We Want?

Marylène Negro is a French artist, famous in the field of contemporary art. She has made thirty videos, screened in both galleries/museums and regular film festivals. Her main issues are depiction and contemplation. Her works often bring about a face-to-face, either two solitudes or two creatures so totally different that nothing but their physical position can point to a relation between them. For example, in 1999, she followed animals in a zoo, a bear and a giraffe, for hours; the result is a film about animality as shot by a human Balthazar, Bresson’s opaque donkey. More often, what one sees is a sound or visual representation that the film contemplates, not to understand it but to represent it from its limitlessness, until it provokes a gentle vertigo. For Negro, the image represents an area of intercession that defuses the potential violence of a meeting, keeping only the qualities of attention, vigour and benevolence – prerequisites for a possible exchange. The image enables apprehension without prehension.

In X+, Negro takes up what is, for her, a new dimension of human experience: the collectivity. This new issue, which forgets nothing of the previous issues she has treated, raises new questions. What are the aggregating forces that bring forth this drive – brusque or slow, woven from facts, simplifications and resonances that we call, always approximately, collective history? The cinema relentlessly records silhouettes, groups, crowds, masses – fleeting passers-by of a period they are going through, tiny extras of a zeitgeist that carries them along. X+ explores the visual and sound forms of presence thanks to which the argentic traces of these innumerable figures whose existence forms the tissue of humanity persist, insist or dissolve and whose mingled gestures – noticed or unnoticed – make up the supposed collective substratum of a collective history. X+ attains the very principle of figurativity.

On her Time-Line, Negro superimposes ten activist films from a body relegated to the margins of the official history of images, sometimes themselves collective or anonymous. In the chronological order of their production: Here at the Water’s Edge (Leo Hurwitz, 1961), a poetic description of Manhattan by an elder statesman of political cinema; The Exiles (Kent MacKenzie, 1961), a night in the life of an Indian minority in Los Angeles); The Bus (Haskell Wexler, 1963), recording participants on their way to the Civil Rights March on Washington; Losing Just the Same (Saul Landau, 1966), the daily life of a black teenager from West Oakland on his way to prison; One Step Away (Ed Pincus, 1967), California hippies looking for another way of life; Black Liberation/Silent Revolution (Edouard de Laurot, 1967), a rigorous, enraged essay made with the Black Panthers; In the Year of the Pig (Emile de Antonio, 1968), a fresco on the Vietnam war; Winter Soldier (Winterfilm, 1972), conferences by Vietnam War veterans whose testimony on the atrocities drove them into illegality; and finally Wattstax (Mel Stuart, 1973), a concert to commemorate Watts riots in 1965; Underground (de Antonio, 1976), the politics of the Weathermen, who went into radical activism and clandestinity.

From this body of work, Negro has invented a new form of editing that probes depth as well as scope, verticality as well as horizontality. She superimposes the ten films in their linearity, then sculpts their relations of opacity and transparency, so as to bring forth one or several visual and sound images from the volume of the layers thus composed. What emerges are, on the one hand, moments of interlocking that border on magma, thus suggesting an image, an emblem for the perpetual agitation of living creatures coexisting either in time or in space or in people's memories – never meeting, but partaking of the same energy, a coexistence for which no discourse or concept can account. These are the living, in the effervescent confusion of their presence, incommensurable with images as well as with words – mumbling here with all the strength of their modest traces. Humanity delivered from all concepts, history delivered from all teleology.

What also emerges are, on the other hand, new intersections and meetings that form as so many hubs in history, ideas about the political dimension of everyday life. For example, the position of a woman seated in Wexler’s The Bus, who is demonstrating for Black rights, matches the position of an Indian woman in The Exiles: of course, the same enemy exploits and imprisons them. The white man followed by de Laurot on Wall Street can be juxtaposed, point for point, with the little boys sitting in their black ghetto filmed by Landau. The latter’s film describes a particular and concrete situation of oppression; de Laurot’s sends out a structured call for armed struggle, specifically to defend economically condemned children like the two brothers of Losing Just the Same.

Brilliant encounters continually occur in the instantaneous depth of the stratigraphy, but also from a distance: thus the Indian woman protagonist of The Exiles, seated at the movies, is looking at the Times Square screen where Vietnam images that de Laurot caught will later be played. Images, double exposures and connections function exactly like the guns in Black Liberation: they jump from hand to hand, from friend to friend, from motif to motif so as to simultaneously describe situations, and grow the seeds of action. The interweaving becomes a concrete analysis – not of a concrete situation, but of complex movements of history that occur through latencies, resonances, deflagrations, involutions, short circuits, lags and synchronies. In this sense, Negro's film imagines and thinks collective history in the fullness of its complexities, giving each silhouette its status as an historic agent.

X+ plays its part in the contemporary spontaneous movement of films that attempt to re-appropriate and transmit the memory of people's struggles, a work in progress claimed in the USA by Malcolm X, taken up by the Weathermen in their manifesto Prairie Fire (whose cover can be seen in X+), then by Howard Zinn: films such as Profit Motive and The Whispering Wind (2007) by John Gianvito, The Dystopia Files by Mark Tribe (series in progress since 2009), or Film Socialism (2010) by Jean-Luc Godard. These major works came out during a dark period of history. The parenthesis opened in January 2003, when the worldwide demonstrations – among three million people out in the streets – against the start of the second Iraq War were ignored by the Bush administration, proving people’s total powerlessness; it closed in January 2011 with Mohammed Bouazizi's death and the onset of the Arab Spring, thanks to which people once again had access to the power of action, becoming drivers of history once more.

Negro’s film, conceived and made in the hollow of the last fold of this sinister sequence, vibrates with the popular energy born of anti-colonial battles of liberation harboured in frames, like pollen in the trunks of dead trees. It can be likened to political passion, a concept that Antonio Gramsci worked out in prison: a principle of how individuals overcome the oppressive determinations with which they are struggling.

“One may speak ... of ‘political passion’ as of an immediate impulse to action which is born on the ‘permanent and organic’ terrain of economic life but which transcends it, bringing into play emotions and aspirations in whose incandescent atmosphere even calculations involving the individual human life itself obey different laws from those of individual profit.”1

These are the traditional questions re-activated by X+. What is a people? A historical agent? At what point does history start shaking? Like her sources, Negro’s X+ provides an intuition of the irrepressible power of a people fighting. But, contrary to her material (de Antonio, Wexler, de Laurot, etc), this is a people identified not as a nation, a generation or a community, but from the types of its commitment in the world.

This is, thus, the first lesson: political critique conceived as an internationalist solidarity of individual differences, where the most anonymous and discrete shadow is more necessary to history than the most powerful leader – as opposed to the classical internationalism grounded in a hierarchical party. It means that everyone is politically responsible. (Including that you are responsible if you do nothing.) It means also that the cinema, as a figurative art, is especially able to deal with the equanimity of shadows. This is the lesson of Mohammed Bouazizi. It leads to some possible consequences for our conception of cinema, and I wish to consider these consequences as frontlines.

What is an Oeuvre?

In principle, building an oeuvre – in the sense of a career or life’s work – is not a central issue for a committed filmmaker; it is, at most, a secondary concern. The main stake is historical effectiveness, in three related respects:

– The immediacy of the struggle: René Vautier named this cinema of performative immediacy a cinema of social intervention, which has as its aim the success of a struggle and the concrete transformation of a situation of conflict or injustice. This in situ cinema, nowadays accomplished, for example, by Laura Waddington when she follows the struggle of immigrants in Border (2004); or by Godard when he made Prière pour refusniks and Prière (2) pour refusniks (both 2004) – two essays in support of Young Israeli soliders condemned to prison for having refused to do their duty in the occupied territories.

– In the mid-term, the point is to circulate counter-information and stir up energies, as with Masao Adachi’s Declaration of World War PFLP/JRA (1972) and his Newsreel made in Palestine – followed up today by the protesters who are risking their lives filming the massacres in Iraq or Burma, as we can see on the internet and also in films like Burma VJ (Anders Oestegaard, 2008) or This Place is Iran (Anonymous, 2009).

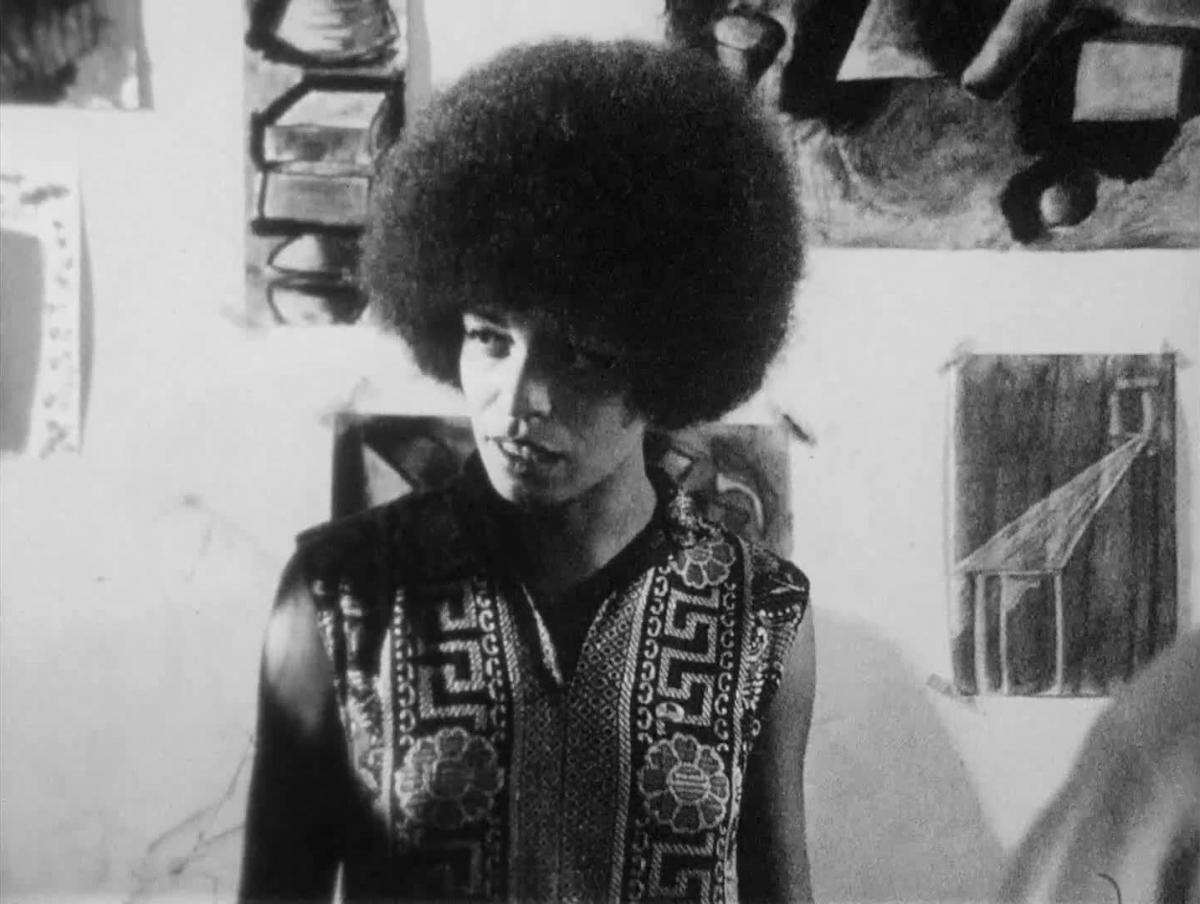

– In the long term, filming has as an objective to keep a record of facts, with a view to history. This dimension involves the document, the archive and transmission to future generations. It is strongly present in Tobias Engel’s No pincha, for instance. Shot in 1972 in Portuguese Guinea among the units of the National Liberation Party, this black-and-white documentary feature follows the fighters in their everyday life, but also aims to conserve the image of Amilcar Cabral in the wake of dreadful cases of assassinations such as Malcolm X’s, Che Guevara’s, Patrice Lumumba’s, or the death of Frantz Fanon. More intimate but just as effective, Yolande du Luart’s very early Angela Davis: Portrait of a Revolutionary (1969-1971) did not have as a primary goal to support an imprisoned Angela (whose arrest took place between the shooting and the editing), but rather to conserve the image, the words, the everyday life of a young militant philosophy professor. The film turned into a call for her liberation only subsequently.

The paths of Vautier, Adachi, Engel, du Luart, Holger Meins and so many others make it possible, and in fact require, that the fundamental notion of an oeuvre be founded anew, removed from the exclusivity of usual criteria. Thus, an oeuvre comprises:

1. Not only works (films, texts …), but acts and gestures as well. In this respect, the greatest inventor of gestures is certainly Godard, as I pointed out in the preface to Documents: “Call on CGT cameramen to sabotage General de Gaulle’s press conferences. Alongside Chris Marker, Bruno Muel or René Vautier, train workers at the Rhodiacéta factory in the use of cameras. Make a national television journalist admit that fundamentally he knows nothing about the news he is broadcasting. Indict the European parliament for inaction in the face of genocide (Je vous salue Sarajevo, 1993)”.2 I will therefore assume that an oeuvre – particularly in the field of engaged cinema – consists of a sum of practices, actions, gestures, symbolic representations (i.e., works), and their mutual relations, accomplished in the course of a life. In this sense, the field of engaged cinema leads us to rethink the very concept of oeuvre as a set of initiatives, not only as a corpus.

2. But what is essential here is not so much to list the gestures of a filmmaker as to consider why a corpus of films has not been made, or no longer exists – because of political commitment. An example is a lost series of films by Masao Adachi who, for fifteen years, shot weekly newsreels with Palestinian fighters; everything burned in a fire in Beirut in 1982, and all that remains of this body of work is the memory of it – much more important for history than the bulk of film celebrated all over in the world of commercial cinema. So, an oeuvre comprises not only the films that are missing, but also the impossible films – unmade because of imprisonment or censorship.

For a cinephile, it is especially difficult to admit that an oeuvre can be major and cherished thanks to the films that are missing from it, because it deprives us of any “visual pleasure”. But we all know, thanks to Freud, that the existence of the fetish is grounded upon the absence of the real object. So let us be direct lovers (as the Maysles Brothers made direct cinema), and let us love directly the revealing absence of major non-existing films – such as the films that Tobias Engel finds no money to shoot in Guinea-Bissau today. Even non-existing, they are more important for the history of cinema than all the blockbusters, which are important only to histories of the American export industry.

Let us consider the filmic case of a work about censored images: William E. Jones’ Killed (2009). Jones is an expert in found footage; his superb works include Tearoom (1962/2007 – “footage shot by the police in the course of a crackdown on public sex in the American Midwest”) or The Fall Of Communism As Seen In Gay Pornography (1998). Between 1935 and 1943, during the New Deal, the Farm Security Administration set up an iconographic bank of 145,000 photographs that structured the realist level of a collective vision of the United States. But most of the images shot by the photographers of the FSA were refused or – according to the word used by the program’s chief, Roy Emerson Stryker – killed. To kill these images, Stryker and his assistants punched holes in the negatives. Jones has devoted a book to these killed images in order to interrogate Stryker’s choices. His film of this material is a rapid shuffle organised around the lethal hole, which allows us to glimpse certain rejected photos by Walker Evans, Theodor Jung, John Vachon, etc.

This leads to a new conception of what a filmmaker is.

What is a Filmmaker?

The dean of committed French cinema, René Vautier, was a member of the Communist Party. But he had to leave his card behind to be able to travel to Algeria and film there, on the side of Algerians. As he explained in an interview published in Cahiers du Cinéma in 2001:

“I was a Communist. I also met Frantz Fanon. At first our discussions were quite heated, later we became friends. At the time, he was already the theoretician of Third World revolutions, and feared that I would appear as an envoy of the Communist Party in the eyes of Algerians. It happened not to be the case. Upon my departure from France, the party had mildly disavowed me, with Léon Feix telling me, ‘You don't represent anything, but you can do what you want’. When you go abroad and you do not represent the Communist Party, you have to leave your card at the local federation. I had dropped mine at the federation of Seine et Oise [near Paris].”3

The historical example of Vautier is now a source of inspiration for a new generation of radical, free, young filmmakers, like Florent Marcie who shot two extraordinary films in Afghanistan, Saïa (2000) and Itchkeri Kenti (2006), and has since shot in Lybia. Or Edouard Beau, who shot a film in Iraq, Searching for Hassan (2008). Even as a member of the Communist Party, and unlike, for example, Roman Karmen who was embedded in the Red Army, Vautier incarnates the definition of art by Herbert Marcuse: art is a force of dissidence.

Conversely, in Camera-Eye, his episode for the collective film Far From Vietnam (1967), Godard explained how he tried to enlist in the service of North Vietnam’s fighters, and how he and Jean-Pierre Gorin were not taken seriously by the Embassy – a very funny and profound moment of definition of Godard’s work by the Vietnamese political delegates: as much of a militant as he is or wants to be, he remains a force of undiscipline.

Since those times, Vautierian and Godardian “undiscipline”, thanks to the discredit of hierarchical political party and the popularisation of cinematic tools, has become a normal use by people of recording and editing machines. One of its best depictions has been written by the British activist filmmaker Laura Waddington in 2006:

“I think it’s never been so important for individuals to go out with cameras (not the embedded nor the professional but those who want just to take time to look and understand.) It’s my belief in a world full of people claiming to ‘represent’ everyone but themselves, the small, the fragile, the unfinished voice – that which searches and refuses to be anything but that – is a kind of resistance.

Perhaps to be a film or video-maker today is to be a sort of itinerant. To know that no deal, no system, no country is so vital to one’s being, that one wouldn’t walk away from it when asked to compromise one’s vision.

I’ve come to love this small, ongoing dialogue with people around the world and to associate it with a kind of freedom.”4

Of course, all previous conceptions of what a filmmaker is or could be remain valid. But we can salute the emergence of a kind of filmmaker who does not consider himself or herself as the origin of expression and feelings. Some filmmakers now are just trying to find ways to help the people’s voices be more hearable, to be heard a little further.

Now, the most frequent maker of filmic images is without any budget or visibility. There is now an innumerable lumpenproletariat of images, unseen and unheard. It leads filmmakers to become the “broadcaster” or “loudspeaker” of unheard voices. Like William E. Jones for the unseen images, but in the immediate present. I will mention three examples.

The first is the Argentinian filmmaker Mauro Andrizzi and his now celebrated Iraqi Short Films (2008). Andrizzi was born in 1980 and is now a major figure in the field of experimental documentary, with four shorts and five features. He studied scriptwriting and graduated from the ENERC (National Film School), Buenos Aires, in 2001. Iraqi Short Films is a compilation of footage shot by a cross section of amateur documentarians: “coalition soldiers, local militia members, private corporate workers and rebels … some of whom held their camera/mobile phone for the last time in their lives.” Andrizzi’s work testifies to a possible reversal: no longer a history of the anonymous (in their most radical state: as cannon fodder), but a history by the anonymous.

The second example is the Canadian Pierre-Marc Gagnon, who in 2009 made a work titled RIP in Pieces America; a sixty-two-minute film made with clips banned from the Internet. The result is an astonishing depiction of ordinary people devastated by the ideology of fear and hate spread by the media. A portrait of the USA from the viewpoint of its frailest (in terms of freedom of spirit) citizens. Paranoia collectively incarnated; a nation of zombies.

A third example can be found in the French documentary filmmakers Anne-Laure de Franssu and Malian activist Mory Coulibaly. In 2006, a thousand people were caught in the pitiless nets of the anti-migration policies of the French government. Expelled by the hand of the military from Building F of the City University at Cachan, thrown out into the street, many of those who were without lodgings, and often also without papers, gathered together in the Cachan gymnasium. Coulibaly, delegate of the expelled families and actor in the struggle, filmed the events, helped by de Franssu and her organisation Words in Images. He titled his film Regardez chers parents – “look, my dear parents”, meaning: look at what France really is.

Then, de Franssu followed Coulibaly on his journey to Mali, in the course of a tour of towns and villages, where he projected Regardez chers parents to spectators who were astonished by the violence of the police state, and whose remarks – often less sorry for themselves than for the condition of contemporary France – constitute one of the most powerful critiques, to this day, of the government’s policies. The result is a marvellous film about the power of images: Sou Hami: The Fear of the Night, a feature completed in 2010. Sou Hami is one of the principal, contemporary, visual gestures concerning cinema that has been made. It is a battle of images: the battle of Coulibaly’s video images against collective beliefs about France, by the Malian people but also by the French people, who have elected a racist government.

Now we come to a reflection about form.

What is a Political Form?

Of course, every film is political, in the sense that it is ideological. But in the sense of an affirmative fight, there is a need to found Aesthetics anew, from out of the political.

A certain prejudice (and a quite useful one, when it comes to refusing to take an oeuvre into consideration) has it that committed cinema, caught in the material emergencies of history, remains indifferent to aesthetic questions. This is a pathetically decorative conception of formal ambition since, on the contrary, the cinema of intervention exists only insofar as it raises the fundamental cinematographic questions: why make an image, which one, and how? With whom and for whom? With which other images does it conflict? Why? Or, to put it differently, which history do we want?

Attached to structural singularity, criticism (according to a logical tendency) privileges singular structures. The classical models of totality and totalisation dissolve in the face of the potentialities of structural invention – each part is invited to discuss its belonging to the whole. In 1799, Friedrich Schleiermacher uses this superb political metaphor, very probably the origin of Godard’s republic of images: “Poetry is a republican speech: a speech which is its own law and end unto itself, and in which all the parts are free citizens and have the right to vote.”5 The poetic is defined thus: no longer as something that obeys the rules of organisation, and therefore a conventional distinction between prose and poetry (in the limited sense); but as something that develops its own particular modes of organisation. Each moment of the work is capable of developing its own legitimacy.

For contemporary political filmmakers, the most important “moment” is the relationship between images, the raccord or the hiatus. What are the links between two members of the world of images? Is it a republic, or is it a dictatorship?

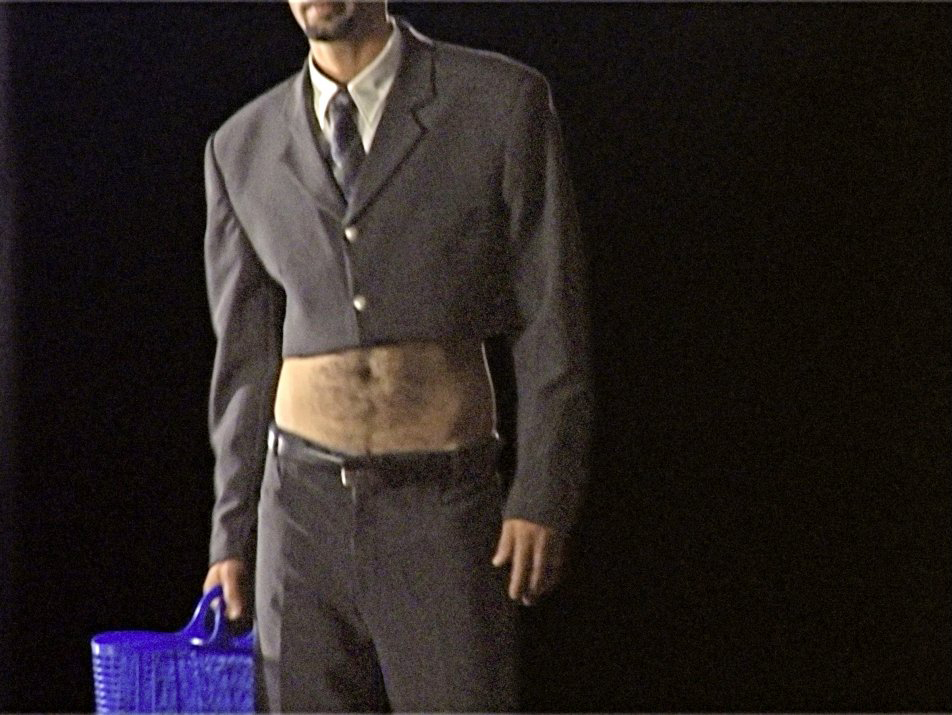

Let us take an example from an Arabic Israeli artist, both painter and filmmaker: Sharif Waked’s Chic Point: Fashion Show for Israeli Checkpoints (2004). Chic Point is a kind of apogee in visual irony, directed at an unending, daily war. The first answer to the situation is practical: in the credits, we can see that the people involved have both Palestinian and Israeli names. This is a first, internationalist answer. But further, Chic Point presents, in its actual images, a critical point. The film relies on clear-cut oppositions that mutually highlight each other:

– The mobile video opposed to the immobile pictures of photography.

– The videographic colour against the black-and-white in fixed images.

– The video’s plastic lightness against the archival dimension of photos.

– The live music of the fashion world against the total silence of the political world.

– The frivolousness of the fashion show opposed to the tragic character of military oppression.

– The glorious, dreamy presence of young bodies opposed to the unbearable humiliation of attacks against human dignity committed by the Israeli army.

– The admiration/attraction contract usually linked to a fashion show opposed to the aversion, antagonism and repulsion revealed at the checkpoints.

– The abstract videographic space (only black, we see no podium or décor) opposed to the precise time and space of the incidents and arrests at the checkpoints.

– The angelic beauty of the male bodies against the ordinary and sometimes disfigured bodies of the Palestinian victims.

– The fluid continuity of the bodies appearing to become visible opposed to the dry discontinuity of the photographs.

– The hypnotic ambiance of the pleasant fashion show opposed to the concrete, tough, daily life of repressive situations.

– The oneiric strangeness of the costumes against the daily, concrete set-up of repression.

– The absent and professional look of mannequins (avoiding too much of eye contact, where we find ourselves beyond the look) opposed to the blindfolded eyes of the Palestinians under arrest (no more possible vision, we find ourselves underneath the look).

The violently fractured composition of Chic Point, between thesis (the fashion show) and antithesis (the photographs) forces our mind to complete the effort to synthesise or at least aggregate – that is, establish links between the two slopes of the film. Everyone will draw his/her own conclusions according to the political situation, but some relations clearly impose themselves:

– Historical relation between allegory (the fashion show) and referent (the photographs).

– Subversive relation between parody (the fashion show) and obligation (military occupation).

– Dialogue relation between ironical transposition (the film) and deaf-and-blind oppression (historical situation).

Urged on by the contrast between the two parties, the audience’s mind becomes simultaneously active as to the very nature of such a fracture. It appears as rich and polysemic, in terms of whatever allows us to understand it:

– Artistically, the fracture between the two slopes of the film is a border; imposing itself as a mark between the two image regimes (video/ photograph).

– Formally, it is a tear; reproducing, in the very syntax of the film, the signs of notches, cracks, wounds and scars that attack clothes and, underneath that, attack bodies and land.

– Emotionally, it is a break-up; tackling the speculative violence that the spirit must endure to overcome contradictions.

– Dialectically, it suggests a qualitative jump; pointing to a possible exit out of history (think of something else, another way, vis-à-vis an endless war).

We can also observe how some concrete elements discretely cross both slopes of the film:

– The athletic bodies and pauses of the two arrested Palestinians, blindfolded with their hands tied behind their backs, spontaneously remind us of the attic poses that are similar to the models of classic beauty, and vaguely remind us of the mannequins.

– All persons are male.

– Dialogue and discourse are irrelevant in both contexts.

The principle of non-leakage between two worlds, of whatever nature (space, time and symbolic system) appears thus aesthetically unbearable and impossible. Chic Point is loaded with vulnerabilities: it comes from a country that does not exist (Palestine); it is made with non-conservable material (video), in a badly classified form (polemic haiku), in the name of a discourse without any right to existence (the conflict transformed into a contradiction, the contradiction allowing thought to travel beyond war). Therefore, this lively, fragile film creates many links and subtle attachments between real history and its apprehension – which is the precise place of politics in the republic of images.

We come at last to a final but non-conclusive proposition concerning cinephilia.

What is a Cinephile Now?

Now we can live a renversement, a reversal: thanks to variety of forms of filmmaking and financing, a cinephile can become a producer. He or she can, of course, make a film himself; but s/he can also produce the films he thinks are necessary for the present, and for the future. This was the case with the campaign that led to the making of Far from Afghanistan (2012), by an international collective of filmmakers led by John Gianvito. During the drive to raise production funds via Kickstarter, he communicated this message to followers:

“I am writing you today to share a project that I feel very strongly about. I, along with a team of some of filmmakers I admire most in the US and backed by a dedicated production team, are in the process of completing a new film: Far from Afghanistan. We hope this project will generate vital dialogue around the war, which, in 2010, surpassed Vietnam as the longest war in US history. This October marks one decade of war, underscoring the urgency of goals and elevates the opportunity to rally for change.

I will be contributing a 10-20-minute segment, along with Jon Jost, Minda Martin, Travis Wilkerson, and Soon-mi Yoo, all of whom have been working tirelessly and without any financial support to create a film that looks deeper at the issues these ten years of occupation and violence have wrought. Additionally, this summer five Afghan filmmakers gathered wide-ranging portraits of the contemporary life inside Afghanistan, material which will be woven into the fabric of the film. The project plans to connect with and provide humanitarian organisations with aligned missions, both in Afghanistan and domestically.

Others who have joined together to answer the call on this project include our producing team: Steve Holmgren, Mike Bowes, John Bruce, and Matthew Yeager. Editing efforts will be taken on with Pacho Velez and Robert Todd.”6

So this is an example of how we can produce together, as citizens, an internationalist film.

- 1Antonio Gramsci, “Politics as an Autonomous Science,” from Quintin Hoare & Geoffrey Nowell-Smith (eds. & trans.), Selections from the Prison Notebooks (New York: International Publishers, 1971).

- 2See Nicole Brenez, David Faroult, Michael Temple, James Williams & Michael Witt (eds), Jean-Luc Godard. Documents (Paris: Centre Pompidou, 2006).

- 3See dossier in Cahiers du Cinéma, no. 561 (October 2001).

- 4Laura Waddington, “The Small, the Fragile, the Unfinished Voice (2006)”.

- 5See Friedrich Schleiermacher, “Critical Fragments,” in P. Firchow (trans.), Philosophical Fragments (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1991).

- 6See documentation here.

This text has been lightly edited from a presentation prepared as a Keynote for the World Cinema Now conference at Monash University, Melbourne, 28 September 2011.

Translation assistance and editing by Adrian Martin

© Nicole Brenez and Screening the Past September 2013