The Animator as Avatar

This text originally appeared in AS CAHIER #1: Chris Marker (Antwerp: Muhka, autumn 2008), a publication dedicated to Marker’s work, on the occasion of Staring Back, an exhibition of his photographic work in the Fotomuseum in Antwerp, an exhibition project of MUHKA.

“He wasn't even thinking of turning to his colleagues to warn them that their students' identical grades were in fact not a whim of the computers. Rather he wished to find a comfortable sentry post from whence to observe the unfolding of the rest of the events with the detachment of a cat.”

– From the short story Phenomenon (n.) by Chris Marker

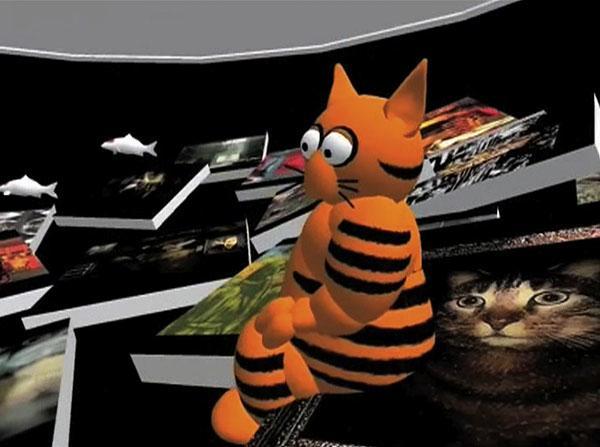

A notorious cat lover, Chris Marker also likes to live nine lives of his own, and at the same time. Alongside his activities as a writer, critic, photographer, scriptwriter, filmmaker, photo editor, media artist and cartoonist/blogger, Marker has recently also begun frequenting Second Life, where his avatar bears the name Sergei Murasaki. Under this guise, Marker consented to a rare online interview, where he advances the notion that he never even considered himself to be a filmmaker. Ja-mais.1 Furthermore, he thinks the label of ‘multi-media artist’ sounds altogether too contemporary. Rather, Marker prefers to be characterized as an artisanal bricoleur, albeit one who always puts his own unique signature on everything he tinkers with. This brings to mind Jean Cocteau, to who Marker devoted one of his early long essays; a jack-of-all-trades who writes; someone who injects graphic poetry into everything he touches. And someone who in no way limits himself to a single technological medium in order to stimulate the viewers’ memory and imagination, to provide them with ‘revelations’.2

The first medium with which Chris Marker began working in the 1950’s was the book. He started out as a poet, and almost simultaneously as a reviewer, and then worked as a photographer and editor of travel guides. Even before the Nouvelle Vague broke onto the scene, Marker, together with Alain Resnais, had pushed the boundaries of documentary film. In the meantime, his La jetée (1962) and Sans soleil (1983) have inspired several generations with their obsessive reflections on technology and memory, camera and the subconscious, reality and fiction. During the centenary celebration of film, Marker produced a film-essay, Level 5 (1995), modeled on a computer game, and voluntarily his final feature film. Concerning his recent television documentary, Chats perchés (2004), Marker, alias Murasaki, relates how much he enjoyed making a film with his own hands, with no more than his ten fingers, and without outside intervention: “And then to sell the DVD personally on the Saint-Blaise market ... I have to admit that I felt a sense of triumph: straight from the producer to the consumer. No surplus value. The realization of Marx’ dream.”3

This summer, Marker added a short film to the ever-expanding universe of You Tube: Guillaume Movie (2008).4 It is a logical step and a typical maneuver for a living legend who embraces every new form of audio-visual technology in the post-cinema age enthusiastically. Clearly exchange and participation have gradually gained in importance for Marker, as he prefers to address the viewer in a way that is not authoritarian or unilateral. This explains the meandering structure of his documentary essays, the liberating abundance of images in the installation Zapping Zone (1990), the inexhaustible archive of Immemory (1997), the unpredictable combination of images in the installation piece Silent Movie (1995): an overarching image becomes increasingly impossible, the reservoir of possibilities continually increases. Marker likes to confront viewers with themselves, and induces them to take a personal journey of exploration. With Marker, the puzzle is never complete; he carefully avoids a view of the whole. His strategy is always again a combination of an open system and a consistent philosophy. He weaves them together indirectly in a footnote to his early text on Cocteau: “I do not think it is necessary to specify the location of the numerous quotations by Cocteau in my article. The curious reader would be better served by looking for them on one’s own, and discovering others.”5

Clandestine

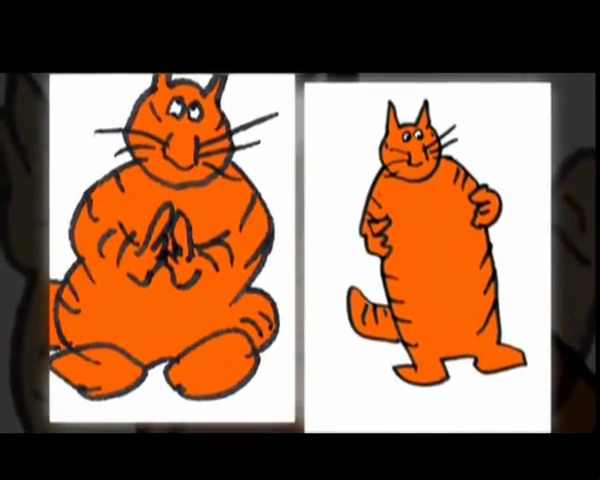

Guillaume Movie is a simple, playful animation film featuring the same cartoon-cat that stubbornly insists on showing up in his work ever since it played the role of the laconic guide in Immemory. Perhaps Marker wants to indicate that all the new projects in which the cat appears are extra extensions of the CD-ROM project? He also regularly e-mails cartoons to his circle of acquaintances, cartoons in which Guillaume formulates his whimsical considerations on current political events. Marker’s activities have always had an activist quality to them. His commitment is already unmistakable both in his early work as a critic as well as in his first art works. In Staring Back, he recalls how he captured his first images of demonstrations with a stolen camera. “During those years I came to the conclusion that the only sensible weapon against the cops could be a film camera. Not that glorious but, at times, efficient. With a small 16mm contraption, stolen from an UNESCO drawer, I caught my first demo footages, rather fuzzy, stealing light from the television people. And that was a turning point in my film ‘career’ (that despicable word). In another time I guess I would have been content with filming girls and cats. But you don’t choose your time.”6

Marker’s poetic activism does not impose ready-made ideas, nor does it exact any conclusions. As the collection of his early reviews, entitled Commentaires I & II (1961 & 1967),7 immediately makes clear, he prefers to play the role of commentator. His lighthearted protest always contains an extremely personal, even private aspect. Marker never gets up on the soapbox to broadcast his indignation, but prefers to formulate a serene, reserved form of protest. In Si j’avais quatre dromadaires [If I had Four Camels] (1966), it sounds like this: “The resistance already exists, a clandestine bliss.”8 For the prologue to this filmed photo-essay, Marker quotes the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who was the likely source of inspiration for the exotic name of his current pet, Guillaume-en-Egypte.9 The opening motto of Staring Back is also a quotation from the sound track of Si j’avais quatre dromadaires.10 It therefore does not come as a total surprise that, after it had disappeared for years (a decent filmprint no longer exists), for the Antwerp version of Staring Back Marker revisits this film on a video-monitor in order to enter into dialogue with the photographic images. Si j’avais quatre dromadaires consists exclusively of photos Marker captured in twenty-six countries between 1955 and 1965. As Bill Horrigan outlined in his essay,11 the primary inspiration for Staring Back was his contemplation of photographic stills of a number of anonymous, expressive faces from the filmed material for Chat perchès [Perched Cat], a documentary about one of Marker’s younger kindred spirits whose form of intervention was to mark everywhere he went with a graffiti-trail of cats.

It is clear that Marker never was an objective reporter. His use of montage interventions, a voice bantering philosophically, or – once he switched over to electronic media – distortions of electronic images always provided his reports with a recognizable imprint. Instead of graffiti, the introvert Marker opted for graphic software programs. The faces of the demonstrators, as well as all the additional two-hundred old and more recent photos from Staring Back, were noticeably manipulated with Photoshop and other programs. The formulation of commentary and notes can equally be achieved with the pen, the camera or the computer mouse. The multi-media age could not emerge quickly enough for Marker. Already on the occasion of the premier of Si j’avais quatre dromadaires, his friend and colleague Alain Resnais aptly suggested: Chris Marker is the prototype of 21st century man.12

After his solo debut as director, Olympia (1952), Marker immediately continued working as co-director of Alain Resnais’ Les statues meurent aussi [Statues Also Die] (1953), for which he wrote the voice of the critical commentator. After a number of documentaries, Resnais then made L’année dernier a Marienbad [Last Year at Marienbad] (1961), loosely based on the cult book The Invention of Morel (1940) from the Argentinean author Adolfo Bioy Casares. In his Second Life interview, Marker-alias-Muraski gave a pithy reply to the question of how he would introduce himself to someone who did not know him: “I would say that he should read The Invention of Morel and then go to the cinema.” But Second Life, which according to Marker is the ideal universe for the super-bricoleur, approximates oneirism – the porous intermingling of reality and virtuality – even better than cinema does. “If I could, I would withdraw into Second Life forever, like Brandon on Tahiti.”13 While his short story “Phenomenon (n.)” (1999) can be interpreted as a clear warning for widespread indifference and millennial doom, Marker himself has long been convinced about the liberating possibilities of digital culture for an engaged and at the same time detached spirit such as his.

Anonymous

Guillaume can rightly be considered as the first and still most important avatar with which Marker took the step from cinema to new media. Now and again, Marker actually flirts with the notion that he himself is a reincarnated cat. Elephants and owls also make frequent appearances in his world, but with them he never becomes obsessive or personal. Of course, Guillaume is also one of the many false trails with which he, among other things, puts his role as cinéaste d’auteur into perspective. This is in stark contrast with, for instance, Jean-Luc Godard, whose personal appearances as a media personality became his trademark. Chris Marker on the contrary, even refuses to have his picture taken. There are a scant few images in circulation, in which his face can be distinguished, and even then only partially.14 In Staring Back, there is however a photograph that depicts him just at the moment of his arrest at the Pentagon in 1967. Marker’s notorious anonymity can thus simply be explained as a strategic move; if you are going to protest, it is best not to be recognized or become registered. And for anyone who enjoys strolling in Paris and taking the metro, it is better not to be a famous Parisian.

The noblest unknown from the pantheon of the cinéma d’auteur therefore also claims that, being an enthusiastic traveler, it was for merely pragmatic reasons he chose to go by a name which would be easily pronounced internationally. Marker was born Christian François Bouche-Villeneuve in Ulan Bator (Mongolia), but it also could have been in Belleville France. He is no stranger to dissimulation. ‘Marker’, or ‘felt pen’, is not exactly the most poetic pseudonym, although it does evoke connotations of the Magic Marker, a pen with transparent ink which can nevertheless invoke colorful images in so-called ‘magic picture books.’ Marker prefers to be as invisible as possible, but at the same time he enjoys negotiating the game of appearing and disappearing. As an audio-visual commentator armed with his caméra stylo, a concept by Alexandre Astruc which in 1948 formed the basis for the subsequent blossoming of the cinéma d’auteur, Marker likes to highlight exceptional passages in the real world without worrying about a classic form of narration.

Much more radical than Resnais, who apparently showed a persistent interest in experimenting with narrative structures but who never entirely abandoned cinematic language, Marker may be characterized as a third-generation cinephile. Cinema of course remains the breeding ground and frame of reference for his way of thinking and acting. But when it comes to technology, he has no nostalgia. It is precisely in the new forms of image production and reception that he sees an opportunity to permanently renew his cinephile enthusiasm. As illustrated in the text about Leila Attacks (2007) included in this cahier, even when Marker places a short film on the internet in order to participate in a one-minute festival, he continues to punctuate his commentary with cinephile nods to both film classics as well as cult television.15 Post-classical cinephiles are typified by their hybrid nature, their diversity and a strong sense of auto-reference.16 In Leila Attacks, a short film about a rat and a cat, Marker begins characteristically with an introductory title card as concise as it is pompous: “Chris Marker: the best-known author of unknown movies.” Indeed, Marker’s films are very rarely shown, and the master of the audiovisual essay goes to great lengths of his own to remain a character without a face. Yet at the same time, Marker is now more present than ever: in exhibitions, books, and finally on DVD-releases. But a taboo seems to rest upon anyone’s ambition to summarize the totality of his work. Marker is anything but pleased that projects which bear witness to a thorough research are shown together with works made for specific occasions, works that he still recognizes as belonging to a specific time and place, but which do not belong in a retrospective “for a contemporary audience.”17

For example, there are numerous, often significant films which existed prior to La jetée, but according to Marker they no longer need to be shown. On the occasion of a retrospective for the Paris Cinémathèque in 1997, Marker claimed that his debut came in 1962, whereas he had directed or co-directed at least eight films since 1952.18 In theory therefore, the only person who could claim to have some knowledge of the entirety of his work could only be a first generation cinephile, someone of approximately the same age as Marker (born 1921!), and with an equally vivid memory. Such a situation inevitably leads to mystification, as does the democratic but simultaneously surreptitious manner in which Marker, or one of his alter-egos (Chris Villeneuve, Fritz Markassin, Sandor Krasna, Jacopo Berenzi and Chris.Marker), places his latest bricolages on websites. Whoever does not belong either to his inner circle or to the academic world (which occasionally is granted access to his complete catalogue) can only discover the latest developments in Marker’s world with much delay, if at all.

Vanity or strategy? Probably a combination of both. It is understandable that the unclassifiable Marker, who has made his trademark of mnemotechnical games, is not a fan of retrospective overviews. It is not for nothing that the term ‘immemory’ is a Markerian neologism for ‘impossible memory’. A chronological list probably leaves him with the impression of an obituary, while the essence of his method is precisely the diachronic. The free associations that Marker constantly weaves into his essays are also there to mobilize the viewer, and are based on the idea that every film, every creation is but a work-in-progress. This also gives legitimacy to his method of continually referring back to and reworking ‘old’ film material in Zapping Zone, Immemory, and Staring Back, etc.

Hybrid

For Marker, the active component in the term ‘remembrance’ is clearly more important than a passive, fixed ‘memory’. By variations on his themes, Marker instigates his own quiet revolution: an attempt to return each time also implies an attempt to reverse of the order of things. Every repetition adds new meaning. Like a musician or stage actor, Marker employs the concept of ‘repetition’ more in the sense of rehearsal than of a definitive performance. This might also explain the present tense in Marker’s title Staring Back, as well as the way he embraces every audiovisual medium that escapes from the linear structure of classic film. Reevaluation of recorded images in order to reanimate and transform them is a constant motivation behind the work. In Lettre de Sibérie [Letters from Siberia] (1957), for instance, he provided three ideologically different commentaries for the same material, one after the other. There exist three different versions of Le fond de l’air est rouge (a.k.a. A Grin without a Cat, 1977): the film was originally four hours long, but that became three for the British television showing in 1988, and in 1993 the film received a new epilogue. The photo prints in Staring Back now look entirely different than when they were first developed.

While Marker worked for years as a professional photographer, Staring Back is de facto his first photo exhibition. Prior to that, Marker always situated his camera-images within the context of a greater whole. Simultaneously ‘illustrative and allusive’, as Bill Horrigan describes the photographs in his essay, they had previously appeared in the format of a newspaper, once as a book of photos,19 a film, an installation (the Photobrowse section in Zapping Zone) or a CD-ROM. While Marker’s title, Staring Back, immediately suggests the act of retrospection, for him it is also and above all a new project, and qua model of presentation even a prototype, and as such is again new territory. Some images are more than half a century old, but in each case they are new prints, and Marker first works on every shot with a digital pen. He adds a little annotation here and there, but nowhere can one detect a chronologically ordered whole or a nostalgic journey back in time. As a non-linear story-board on the wall, the elaborate photomontage becomes a reflection on politics and the individual. Despite their extreme diversity of place and time, there is a striking coherence, as if Marker’s primary goal is to make a statement about history, solidarity and personal perception.

Marker always made an active choice to be an eyewitness, both of the major and the most trifling of events, around the Pentagon or on the corner of his street in Paris. Central to his work is his intimate involvement as a committed participant in political demonstrations both then and now. Staring Back is anything but a retrospective, it is rather a testimony and the silent statement of an ever-alert world traveler. The visitor/viewer also has to travel, or at least take a stroll along the erratic route charted by the many dozens of photos on the wall. An overarching image of this exhibition is impossible; the capricious montage of images induces one into an active reading which requires time. In the introduction to his film, Si j’avais quatre dromadaires, Marker puts into words his most important motto as a producer of images: “The photograph is the hunt, it is the hunting instinct without the desire to kill. It is the hunt for angels. You trail, you aim, you fire and – click! Instead of a kill you create an eternal life.”20 The way in which the photographs in Staring Back are ordered in a few large clusters, free from any chronology or formal logic, reminds one of the way in which the chapters are divided in Si j’avais quatre dromadaires (Le chateau and Le jardin). With a dialectical organization based upon the subheadings (I Stare 1, They Stare, I Stare 2 and Beast of), Marker emphasizes that he wants to disarm himself and be subjected to the gaze of the one being photographed, despite his controlling position behind the camera. It is above all a question of establishing the magical eye contact, an equivalent exchange of glances. A few hundred photos, a mix of artist’s portraits, political demonstrators, anonymous beauties, famous faces and various animals look forward to the visitor. They await an answer to their gaze so as to be brought back to life and reality. Eye to eye with animals? As Marker noted regarding Leila Attacks: “As if only people can look.” In both Si j’avais quatre dromadaires as well as Staring Back, animals offer warmth and at the same time put things into perspective. Solidarity and tenderness can assume many forms. Or as Marker suggests through his photo-film: besides the law of the jungle there is fortunately also the one of the garden.

Hiatus

Owls at Noon ... Prelude: The Hollow Men was conceived specifically for the spatial outlay of the Yoshiko and Akio Morita Gallery in the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The installation consists in a long horizontal row of eight video monitors that hang in the darkness like a flickering strip of film, resonating in relationship to Manet’s panoramic Water Lillies in the neighboring space. In his own unique way, Marker is also an impressionist, using optical effects and illusion to evoke the fleeting, the momentary, rather than striving directly to achieve monumentality. The point of departure for Owls at Noon ... Prelude: The Hollow Men are again photographic documents, the graphic character of which is strengthened on the one hand by applying electronic image filters to them, and on the other hand by alternating them with a graphical interplay of slowly animated words: a poem by Thomas Eliott from 1925. The size of the images and the black-and-white values correspond with the nearly identical shape of the photographic prints from Staring Back. And again the photographic images (recordings from the period of WWI) are rather ambiguous, as they become revitalized through their reframing and computer graphic manipulation. The alternation of two image montages on various screens strongly emphasizes the sequential and the interval, the hiatus between the images.

Like any animation filmmaker, Marker plays upon our perception and memory; he expects that we bring the images back to life by filling in the intervals ourselves, by associating along with them and by contributing our own connotations and remembrances to the impressions on our retina. For Marker, film was never simply the reproduction of actual events, a specific length of time that can be reproduced in an analogue form. There is always the subjective timbre of a commentator’s voice or of image manipulation which endows the work with a personal signature. And which calls the objective reality of the trail of images into question. Or as Marker warned his reader at the beginning of his book of photos and texts, Le dépays (1982): “The text comments on the images just as little as the images illustrate the texts. They are two series of sequences which obviously cross one another and form a sign, but it would be uselessly exhausting to try to confront them with each other.”21

Like any animation filmmaker, Marker generates his own, mythical time by accumulating stationary, disconnected images arranged so as to provoke a subjective perception in the viewer. According to the short autobiographical sketch, “Chris Marker Filmmaker”, his first, childishly naïve attempt at cinema actually consisted of a cartoon about his cat Riri. That principle of animation is not so much a recent method that just happened to have crept into his works from the videograms of Sans soleil onwards; his most famous film, La jetée, is also actually a slow motion animation of photograms, a film which, just like Si j’avais quatre dromadaires and any other two-dimensional animation film, was filmed using an animation stand.

Intuitively this approach was present already from the very beginning in the reviews that Marker wrote for magazines such as Esprit. In 1951, for example, Marker reflected upon the aesthetic of animation film, through his review of a doctoral thesis at the Sorbonne. Then already he contested the dominance of Disney as well as his implicit petit bourgeois mentality. In his argumentation, Marker displayed a broad knowledge not only of cartoons but also of artistic animation, and gauged the ideological potential of the medium. “Difficult to determine if the Bayeux Tapestry is intended to be an ideogram or a chronicle. An what is it most explicitly preceding: animation film or the newscast? Alexander Nevski or the Three Little Pigs?” A bit further Marker wonders whether the animated film can indeed be something more than a technological ‘coquetterie’ of the image, an intentional anachronism, a marginal art form.22 Ever since the first fully-fledged animation film, Fantasmagorie (1908) by Emile Cohl, animation film indeed operates as a commentator on the ‘real’ world of cinema. Cohl situates his sublime, absurdist-associative fantasy as a meta-film which begins in a movie theatre. Right from the start, Marker also assumes the role of the commentator who assesses reality using the art of cinema as his frame of reference.

The eccentric imagery of Emile Cohl was rooted in the proto-Dadaistic movement Les incohérents, of which he himself was an active member a few decades earlier. Similarly, Marker has an unmistakable fondness for the playful-subversive effect of incongruent image-montages and Max Ernst-like collages, like those which can be found in the X-Plugs section of his CD-ROM. Sabotaging patterns of expectation and desecrating canonic works of art are strategies already put to work in the largely forgotten work of Emile Cohl. With his earliest animation films, Cohl tapped directly in to the tradition of ‘chalk talks’ or ‘lightning sketches’: quick-change drawing artists who created constant transformations with a play of lines on a drawing board right before the eyes of the audience. On the CD-ROM, Guillaume the cat assumes the same performative role as the guide who creates a diversion and at the same time enchants the viewer’s gaze.

Pastiche

The childish naïveté that Marker injects into the game with his alter-ego Guillaume and other avatars is a technique he has in common with the pioneers of animation film. While the technology and the aesthetic of animated drawing is older than that of film (we only have to think of Joseph Plateau and Emile Reynaud), throughout the entire twentieth century animation film has been considered ‘subordinate’ to the more realistic appearance of the feature film. But the leading theoreticians and artists of modernism became very much fascinated with cartoons. “Those who took cartoons most seriously were political revolutionaries,” Esther Leslie contends. “Siegfried Kracauer, Theodor Adorno and Walter Benjamin sat amongst cartoon audiences and developed their thoughts about representation, utopia and revolution in relation to Disney or Fleischer output.”23

Eisenstein, who in 1941 had applauded Disney as the best that American culture had produced, also fulminated a few years later during his wartime isolation in Alma Ata about his disappointment regarding Disney’s ‘betrayal’ of his original intentions and intensity. In his notes on animation film that he collected for his unfinished, theoretical survey The method (which did to some extent find their way into the book, Non-Indifferent Nature – Film and the Structure of Things), he regrets the stylistic break that Bambi signified with respect to his earlier work. “In Bambi, where the point was no longer parodic paradoxicality, but genuine lyricism, a slight erosion of forms of the surroundings and background should have been used, which could then turn into each other and echo the change of moods, creating genuinely plastic music in their flow ... It’s all the more sad and disappointing that in the preliminary sketches for Bambi, all this seems to have been taken into account.”24

A good five years after Eisenstein, in an article from 1951 about the rise of the cartoon-phenomena Gérald McBoing-Boing, Chris Marker also made some critical remarks concerning the growing dominance of Disney. Here he complains primarily about the standardizing effect of what the increasingly conventional Disney tried to achieve, “according to a rule as harsh as the regulations of Stalinist Andrej Jdanov.”25 A half-century later in his blog about the filmed visit of the rat Leila to his apartment, Maker still makes a pastiche of the typical Disney-style charm offensive which went together with the transition of Mickey Mouse into a member of the bourgeoisie: “Well, I say mouse now, but actually Leila was a little rat. It’s just that the word ‘rat’ has no charm while Leila was a real charmer. She will thus go down in history as a mouse.”

Marker, the media-artist who himself likes to play the game of cat-and-mouse with his audience, who dares to intermingle information and inspiration, concludes his song of praise for the contrary, absurd McBoing-Boing with an insight that characterizes perfectly the play of interval and allusion found in every animation film: “Is it really so surprising to rediscover in film, the art of the invisible and the secret, this mystical utterance: one only truly possesses what one has lost.” In Lettre de Sibérie, La jetée and in Sans soleil: time and again Marker begins with the renewed exploration of a childhood image, a form of melancholy verging towards megalomania. For Marker, who is as radical as he is lyrical, memory is above all a form of renewal and internalization. Central to this is not the message; not the source; not the medium; but the receiver. Or as he already stipulated in his essay about Jean Cocteau’s poetics: “the true destination of a poem is not so much to be read, but to be rewritten, in silence, for oneself.”26

- 1Julien Gester and Serge Kaganski, “La deuxième vie de Chris Marker” in Les inrockuptibles 647 (April 22, 2008), 30-33.

- 2Chris Marker, “Orphée” in Esprit (11 November 1950), 694-701. “To doubt the power of cinema to, as they say, ‘ask questions’, is to doubt a technique of revelation as old as the spirit, it is to forget the role of myth itself, which is refraction, simplification: from a scale model to its scale, the patient takes the measure of mystery. This is the function of the fable, of the ghost, of the miracle. From Mount Sinai to Paramount, the only difference is the audience.”

- 3Les inrockuptibles, op. cit., 32.

- 4Guillaume Movie.

- 5“Orphée, 695. « Je ne pense pas nécessaire de préciser les nombreuses citations de Cocteau qui se trouvent dans cet article. Le lecteur curieux aura plus de profit à les chercher lui-même et à en trouver d’autres. »

- 6Chris Marker, Staring Back, (Boston: MIT Press, 2007), 7.

- 7Chris Marker, Commentaires I, (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1961), and Commentaires II, (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1967).

- 8Chris Marker, Commentaires II, op.cit., 168. « C’est vrai que quand on regarde autour de soi, c’est l’horreur, c’est la folie, c’est les monstres... Mais il y a déjà... un maquis, une clandestinité du bonheur, une... Sierra Maestra de la Tendresse... quelque chose qui avance... à travers nous, malgré nous, grâce à nous, quand nous avons la... grâce... et qui annonce, pour on de sait quand, la survivance des plus aimés ? » “It is true that, when one takes a look around, there is horror, there is madness, there are monsters . . . But there is already . . . underground, a clandestine bliss, a . . . Sierra Maestra of Tenderness . . . something that moves . . . through us, despite us, thanks to us, when we have . . . grace . . . an which announces, who knows, a more loving existence?”

- 9Guillaume Apollinaire, cited in Si j’avais quatre dromadaires (1966): « Avec ses quatre dromedaires / Don Pedro d'Alfaroubeira / Courut le monde et l'admira. / Il fit ce que je voudrais faire. » “With his four dromedaries / Don Pedro of Alfaroubeira / Travels the world and admired her / He does what I would rather / If I had those four dromedaries.”

- 10Chris Marker, cited in Si j’avais quatre dromadaires (1966): “It is six a.m. on Earth, six a.m. on the Saint-Martin canal, six a.m. on the Göta Canal in Suede. Six a.m. on the Havana. Six a.m. in the forbidden city of Pékin. The day broke ...” The first showing in many years of Si j’avais quatre dromadaires combined with the photographs from Staring Back is the most important change with respect to the earlier versions from the exhibition in Ohio, New York and Zurich.

- 11Carels refers to the essay ‘Een andere keer’ which, like this article, was part of the AS Cahier #1 Chris Marker, autumn 2008.

- 12Alain Resnais, citation in Avant-Scène du Cinéma, 165 (March 1975), 63.

- 13Chris Marker (alias Sergei Murasaki), citation from Les inrockuptibles, op.cit., 31. “You have read L’INVENTION DE MOREL by Adolfo Bioy Casares? . . . What I have rediscovered in Second Life is precisely the world of this masterpiece: feeling of porosity between the real and the virtual.” « Vous avez lu ‘LINVENTION DE MOREL, d’Adolfo Bioy Casares ? (…) c’est exactement le monde de ce chef-d’oeuvre que je retrouve dans Second Life : onirisme, sentiment de la porosité entre le réel et le virtuel.(…) Si je pouvais, je m’y retirerais pour de bon. Comme Brando à Tahiti. J’aime bricoler. Ici, c’est le super-bricolage. »

- 14The most ‘official’ photo is a self-portrait of Marker with one eye hidden behind his video camera, his cat Guillaume by his side, staring into the lens. In the center of the photo behind them hangs a pastiche of a film poster with the title Titanic clearly legible. [The image has been added at the top of this article.] In his film, Tokyo-Ga (1985), Wim Wenders also filmed a short encounter with Marker, who hides his face with the drawing of a cat.

- 15Chris Marker, cited in Leila Attacks. In one breath he refers to David Carradine, the hero from the TV-series Kung Fu; Eve, the lead character from a film by Mankiewicz; and Charly, a recent film from Isild de Besco.

- 16Malte Hagener and Marijke de Valck, “Cinephilia in Transition” in Mind the Screen: Media Concepts according to Thomas Elsaesser (Amsterdam: University Press, 2008), 23. “The first generation started their own film magazines, the second now runs many of the major cinémathèques (i.e. Alexander Horwath), while the third generation tends to run websites, digital film festivals or mailing lists”, 26 ... “the latter are able to see technological innovation and new modes of production and reception as opportunities for rejuvenating one’s personal cinephile experience.”

- 17Chris Marker, quotation from mail correspondence with the author (September 11, 2008). « Je n'admets pas qu'on présente en vrac des oeuvres qui au moins essaient de témoigner d'une certaine recherche, et des pièces de circonstance que je revendique tout-à-fait en leur temps et lieu, mais qui n'ont rien à faire dans une rétrospective et pour un public d'aujourd'hui. »

- 18Chris Darke, “Eyesight” – Chris Darke unearths Marker’s ‘Lost Works’ in Film Comment Vol. XXXIX, no. 3 (May-June 2003), 48-50.

- 19Chris Marker, Coréennes (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1962). Le dépays, (Paris: Éditions Herscher, 1982). La jetée (San Francisco: Zone Books, 1992).

- 20Chris Marker, Commentaires II, op.cit. 87. « La photo, c'est la chasse, c'est l'instinct de chasse sans l'envie de tuer. C'est la chasse des anges... On traque, on vise, on tire et – clac! au lieu d'un mort, on fait un éternel. »

- 21« Avertissement au lecteur. Le texte ne commente pas plus les images que les images n’illustrent le texte. Ce sont deux séries de séquences à qui il arrive bien évidemment de se croiser et de se faire signe, mais qu’il serait inutilement fatigant d’essayer de confronter. Qu’on veuille donc bien les prendre dans le désordre, la simplicité et le dédoublement, comme il convient de prendre toute chose au Japon. »

- 22Chris Marker, “L’Esthétique du dessin animé” in Esprit (September 1951), 369: « Il est difficile de trancher: la broderie de Bayeux se veut-elle idéogramme ou chronique ? Que préfigure t-elle le plus, le dessin animé ou les actualitiés ? Alexandre Newski ou les Trois petit cochons ? Emile Cohl en fut un veritable dessin animé, il et vrai, et il paraît qu’on recommence, mais cela ne prouve rien. Le véritable aboutissement de la nostalgie du mouvement et du récit dans notre imagerie ne serait-il pas plutôt le cinéma lui-même et le dessin animé ne serait-il pas un coquetterie de la technique, une anachronisme voulu, un art en marge ? » Marker later shows that he knows his (proto)classics and passes over them in review: “The Fleischer brothers, Betty Boop and Popeye. To the existential ferocity of Woody Woodpecker? To Tom and Jerry? To Andy Panda? To the primitives: Gertie the Dinosaur, Koko the clown, Crazy-Cat, Oswald the rabbit? To Paul Grimault? To Soviet animation? To Walter Lantz, Tex Avery, Philip Stapp, Saul Steinberg? Not to mention those who, fifty years ago, discovered everything: Emile Cohl, nor the great unknown, Pat Sullivan, whose Felix the Cat contains all the qualities of the Disney characters, plus a freedom that the moral marmalade of this individual has deprived them of! The realm of animation is vast.

- 23Esther Leslie, Hollywood Flatlands – Animation, Critical Theory and the Avant-Garde (London: Verso, 2002), v-vi : “(...) Siegfried Kracauer, Theodor Adorno and Walter Benjamin sat amongst cartoon audiences and developed their thoughts on representation, utopia and revolution in relation to Disney or Fleischer output, or to entertain the idea that the flattening of surfaces and the denial of perspective troubled simultaneously New York art critics and New Yorker cartoonists, not to mention myopic Mister Magoo. Modern theorists and artists were fascinated by cartoons. And those who took cartoons most seriously were political revolutionaries. As such they were anxious to develop new vocabularies for cultural and social forms within a totality that also contained possibility. They were modernists, not ‘high modernists’ and all that implies, but proponents of a demotic modernism that was open to base impulses and ever curious about the shadow side, the mass market of industrialized culture. For the modernists, cartoons – which rebuff so ferociously painterly realism and filmic naturalism – are set inside a universe of transformation, overturning and provisionality.”

- 24Sergej Eisenstein, Eisenstein on Disney (London: Methuen, 1988), 99.

- 25Chris Marker, “Gérald McBoing-Boing” in Esprit (November 1951), 827.

- 26“Orphée”, 701.

This text was originally published in AS CAHIER #1: Chris Marker (Antwerp: Muhka Press, Autumn 2008).

With thanks to Edwin Carels.