Pasolini, Poet of the Ashes

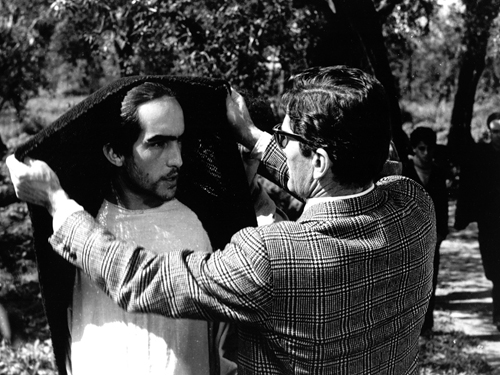

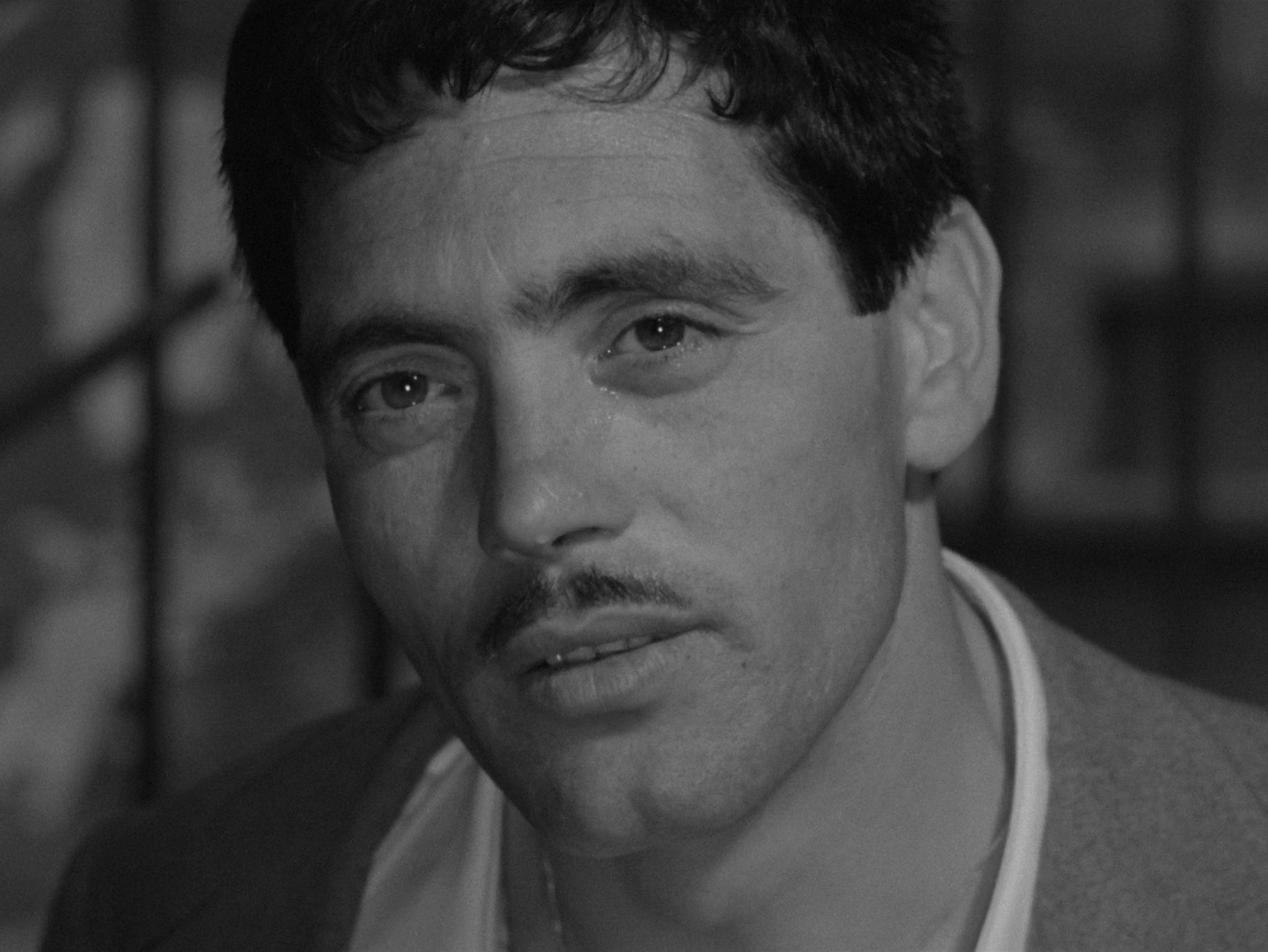

Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922–1975) was an Italian filmmaker, poet, novelist, playwright, painter, actor, and public intellectual, born in Bologna, Italy. Before turning to filmmaking, he had already published several volumes of poetry and two major novels, was active in literary and cultural journals, and was recognised as a leading intellectual. In the fifteen years that followed, until his death in 1975, he made twelve feature films and numerous shorts, wrote and translated for the theatre, continued to publish poetry and essays, painted regularly, and became one of the most prominent and contentious voices in Italian public debate. His early work drew on the Roman borgate he had already depicted in his novels Ragazzi di vita [Boys Alive] (1955) and Una vita violenta [A Violent Life] (1959), yet rather than neorealist denunciation, his debut Accattone (1961) offered an idiosyncratic vision that elevated the marginal communities threatened by Italy’s “economic miracle.”

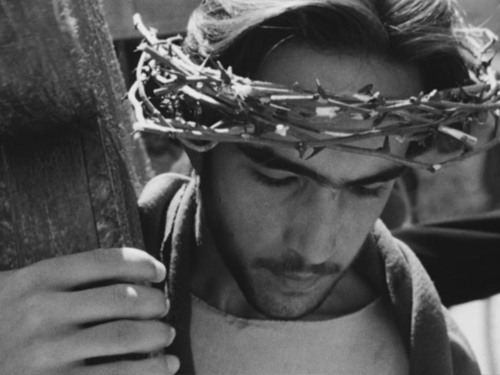

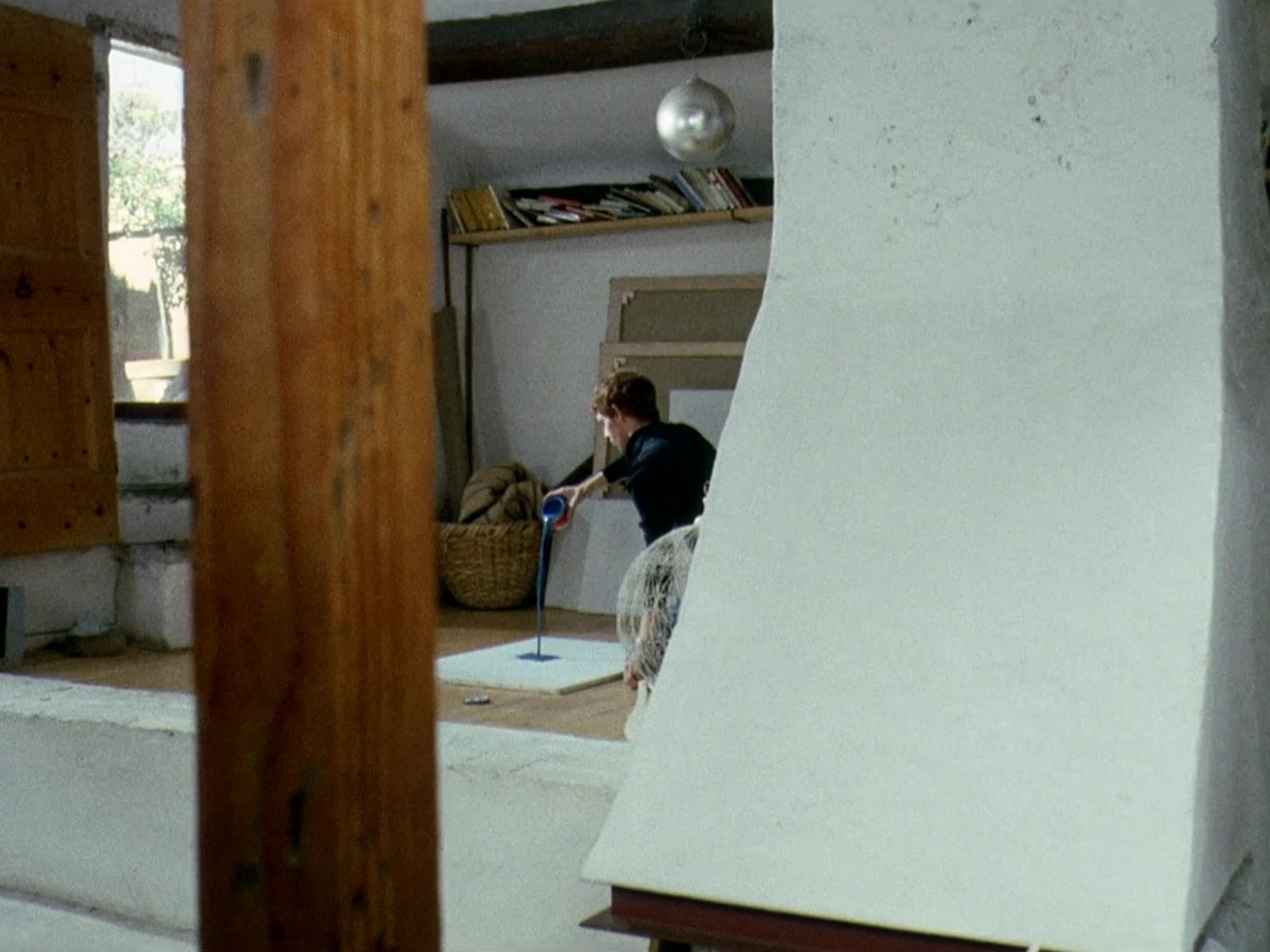

Pasolini approached cinema as another mode of writing, a way of “writing with reality” that could match the expressive force of his poetry and novels. He created what he called a “cinema of poetry,” inspired by the language of reality, often blending different visual forms. “There is no dictionary of images,” he wrote. “There is no pigeonholed image, ready to be used. If by any chance we wanted to imagine a dictionary of images, we would have to imagine an infinite dictionary, as infinite as the dictionary of possible words.”1 This radical heterogeneity marked his entire oeuvre. At the same time, Pasolini’s position as an openly gay man, his complex relationship to religion shaped by a Catholic upbringing, and his commitment to Marxism deeply informed his art. His sexuality and social critique often intersect in his films, drawing him toward the sacred and the pre-modern, and leading him to combine Marxist analysis with Catholic imagery, classical references with contemporary settings, and political concerns with mythic themes.

The year 2025 marked the mournful fiftieth anniversary of Pasolini’s death. After his death, Jean-Paul Sartre wrote a passionate plea for him, warning against the posthumous moralisation and simplification of his oeuvre, which he considered a threat to the radical complexity of his work and his person. “Do not pass judgement on Pasolini,” he wrote, “do not render harmless what was never meant to be harmless.” This collection of texts follows Sabzian’s recent publication WHO IS ME, a Dutch translation of Pasolini’s posthumous autobiographical text Poeta delle ceneri [Poet of the Ashes]. In that text, Pasolini writes: “No artist in any country is ever free. An artist is a living objection.” In that spirit, this collection gathers several texts on Sabzian dedicated to Pasolini’s films, his writings and his lasting legacy.

- 1Pier Paolo Pasolini, Heretical Empiricism, eds. Louise K. Barnett and Ben Lawton (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988), 169.