Flat Jungle: 30 Minutes of Montage

I want to try to describe a piece of editing work with as much precision as I can. It is Monday, the sixth of February, a quarter past 11. The place where we set up shop last November is a partially darkened room in a shed on the grounds of the Cinetone Studios in the east of Amsterdam.

The interior is a bright but indefinable shade of green, the exterior visible from the window has the picturesque gloominess of a set where, decades ago, the last Eastern was shot. At the editing table, Jan Dop, the montage/editing/cutting artist, perched on the edge of his swivel chair cranked up so high he is almost standing, brings to mind a cowboy ready for the roundup.

Next to him, actually slouching half behind him way down on his sacroiliac, his feet up on one table and then on another, sometimes restlessly wheeling this way and that on his chair adjusted to a much lower and more comfortable position, yours truly. In the background, the gentle bubbling of Jan’s Hungarian coffee percolator, a labor-intensive device bearing a marked visual similarity to an old-time steam locomotive. Topped with a good-sized steam whistle, it would make it all the easier to believe in the setting outside, a hamlet in the puszta where stylized violence can break out any minute now. Besides cutting, Jan and I spend a sizeable amount of time prompting the percolator.

We are about three-quarters through with our film on the Dutch Shallows, the Wadden Sea, Flat Jungle. We spent the first couple of months piecing together isolated fragments, clusters of image and sound, that we didn’t arrange into any kind of sequence until a much later stage. We thus approached every piece of film “from the inside,” rather than from start to finish. Each piece is its own middle, as it were. It wasn’t until later, in the completed structure, that it was to be defined as a main component or a connecting link.

This is how you arrive at a structure in which all the elements are treated with the same intensity, since from the start none of the elements are subordinate to any of the others. But now that we have come to this three-quarter point, there are relatively few elements left. In the course of our editing, we have either reserved them for the last part or have simply got them left over. It is easy to get an overall view of the remaining material, and with it we can elaborate upon what our film has already become and round it off in a somewhat more efficient, less tentative way than up to now. The film consists of layers. Layers of natural production and, above them, layers of human production. A rather menacing world has already been clearly depicted by the time the vacation begins: Time Off, Recreation.

Within the colorful span of the entire film, this is the only passage that has been shot in black and white. The vacationers are strangers to the region, old prints, with a touch of nostalgia. Not everything, however, is in black and white. Every now and then the picture switches to full color, when a vacationer’s dream comes true, just for a second, like the brightly hued trailer called Eldorado or the dune waving in the wind. Vacation, that is obvious. A stretch of film estimated at maybe five minutes, after which the planes, the factories and the nuclear plants take over. A short respite, a moment’s laughter, the carefree enjoyment of a sham paradise. This is the passage Jan and I are working on now. We are at the shot of an elderly couple sitting on folding chairs in front of a tent gently flapping in the wind. She is wearing a floppy-brimmed sun hat and gaudy sunglasses, and he, in his little straw hat, looks a lot like W.C. Fields, but nicer. The catchy rhythm of an evergreen sung by Max Woiski, the Surinamese singer, can be heard from inside the tent. The couple sits there without budging, while the music swings cheerfully to the wind. The next shot is of the same couple, but now more of a closeup, they are still motionless, with a friendly look into the lens. The radio plays on. The next shot is from even closer, and the man starts talking.

“When we came here 40 years ago, you could see the seals on the shoals. But you don’t see them any more nowadays and that’s too bad.” (On the radio, the audience laughs at the jokes of a popular Dutch comedian). “You don’t see as many rabbits as you used to either. But they don’t run away as fast,” his wife says. “Yes,” he agrees, “they just stroll around the tent like it is the most normal thing in the world.” As he speaks, he points to something off screen, and that’s when you see the trailer called Eldorado. A conventional link that turns out to be deceiving, someone points and you show what he is pointing at, only there is something wrong. The man is pointing in black and white and the trailer is in color.

After the trailer there is another shot of the couple, but now they are in color themselves. Their bungalow tent turns out to be bright orange. The man’s voice goes on. "The main reason we come here is to enjoy nature. Everything we have seen here on the island, the birds and the rabbits, the dunes, the sea, everything we see here, to us it is the most beautiful place in the world." Gleaming sand reed and a sweeping dune panorama follow the orange shot of the couple, both in color as well. The man’s voice is still heard during these shots.

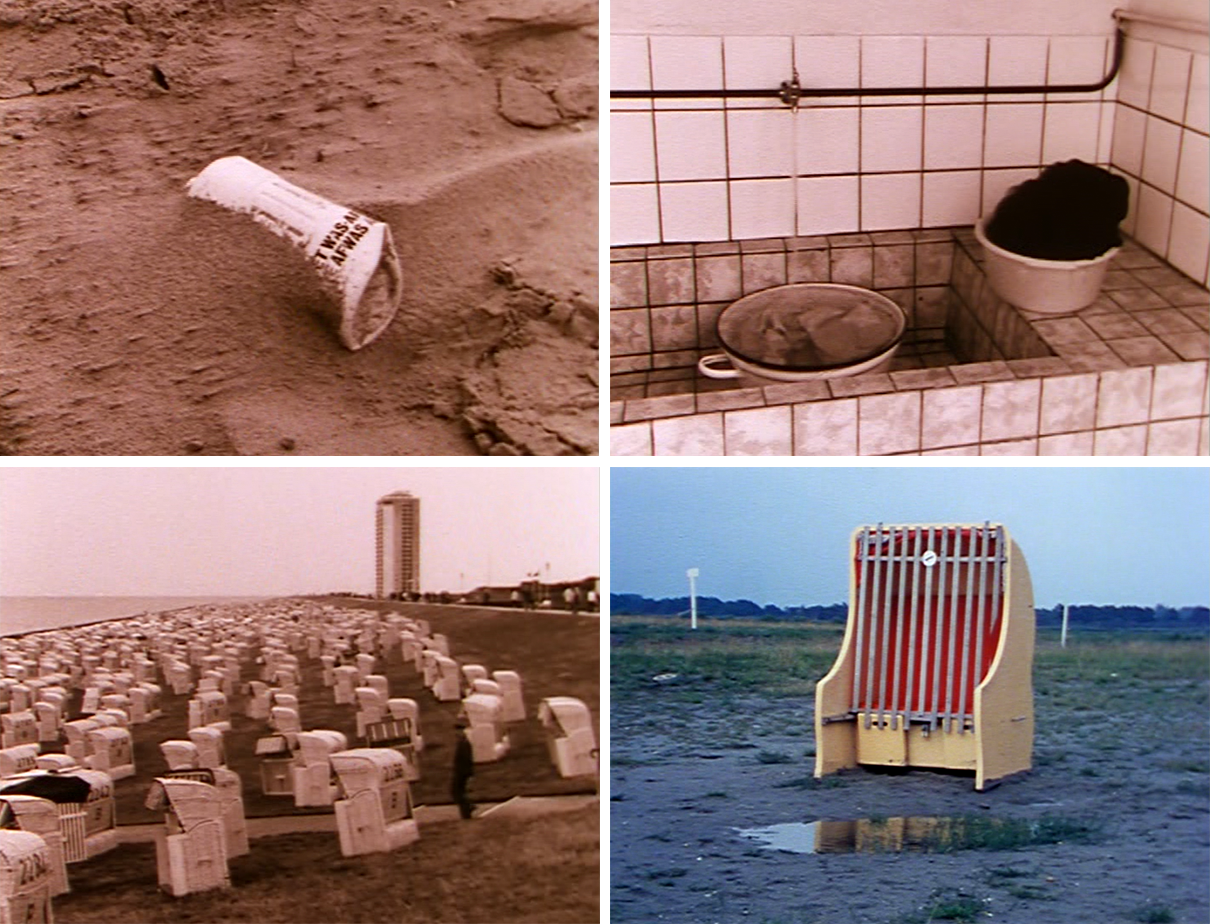

We have already got this sequence put together and now Jan and I are going to try and make it a bit more compact. First, we shorten the spoken text, for example by cutting out “like it is the most normal thing in the world.” We play it back three times just to make sure the sound splice is right. Now “The main reason we come here is to enjoy nature" comes sooner and the shot that goes with it, the orange shot of the couple, can be a little shorter. We also make the sand reed shorter, so the cut to the dune panorama comes right after the sentence starting with “Everything we have seen here.” In order to stay in the rhythm, we also shorten the dune panorama, making the whole sequence a bit more interesting. The man’s text is now longer than the shots, so that it continues into the next sequence, a short series of closeups in black and white of beer cans and plastic bottles, half buried under the sand on the beach. We take advantage of this opportunity to combine these shots with the man’s listing of “the birds and the rabbits, the dunes, the sea,” another deceiving combination: a verbal listing simultaneous to a visual listing, only the two do not correspond.

In order to make the combination coincide, we shorten the previous shots, the orange tent, the couple, the sand reed and the dune panorama even more, so that the text becomes relatively longer and completely covers the shots of the beer cans and plastic bottles. After the cans and the bottles, after the man’s text, there is a shot of a tiled shed with a running faucet above a sink filled with laundry. The shot is static; it is about eight seconds long and is followed by a wide total shot of a coastline with a high-rise apartment building in the distance. In the foreground, there are rows and rows of beach chairs, each with a big number on the back: 2432, 2449, 2352 and so forth.

For two reasons, we decide to turn up the sound of the faucet and let it run over the shot of the building and the chairs. First, for a sharp departure from the naturalism of the “documentary.” Secondly, to stress the association of the numbers of all those beach chairs flowing out of the faucet, with a clear and somewhat coarse effect that presents a different variation on the false links between the pointing and the trailer called Eldorado and between the nature words and the cans and the bottles. A more fundamental variation, since there is no inherent link between the beach chairs and the water from the faucet, which was the case, to some extent, in the other combinations. It all seems very complicated when it’s down on paper like this, but what it boils down to is that there is no medium like film.

In the meantime, it is already a quarter to 12. In this half-hour of the total of 750 hours spent editing Flat Jungle, we licked into shape a sequence of ten shots with a total length of 42 seconds, shortened it and put the sound track in its place. In the course of writing this, I realise that these 42 seconds of film are based, construction-wise, on three sham links that each function in a different way.

The first one works by way of a discrepancy between the action and the off-screen space (pointing/Eldorado), the second one by way of a discrepancy between what is seen and what is said (beer cans and plastic bottles/elements of nature the man lists) and the third one by way of the discrepancy between the objects that are seen and the sound that is heard (beach chairs/running water from the faucet). The third one has no alibi in the actual content and thus gives the biggest jolt. These 30 seconds contain a small escalation concealed under the “documentary” style of the film. Ideally you ought to be able to analyse the whole hour-and-a-half film with this kind of precision. The thought of it! Good God! The nice thing about it though is that while we work, while we play so carefully with the material at hand, we automatically discover all these links. Maybe that is what keeps us seated in these very same swivel chairs for 750 hours. Tiny unexpected perspectives keep opening up.

P.S. We later managed to fit in that Eldorado shot somewhere else. Now the man points directly at the sand reed. It makes it clearer what he means when he refers to “nature.” It makes him stronger and his words can survive the juxtaposition with the shots of the beer cans and plastic bottles. For more or less the same reason, the orange shot of the couple has been left out. It was too “cute” and competed with the color shots of the sand reed and the dune panorama. We have to do nature justice.

This text was originally first published in Skrien, April 1978. This translation was made on the occasion of the retrospective ‘Through the Lens Clearly: A Retrospective Look at the World According to Johan van der Keuken’ held at MoMA in 2001.

With the courtesy of Prudence Peiffer and Josh Siegel

Images from The Flat Jungle (Johan van der Keuken, 1979)