Johan van der Keuken, a Writing Filmmaker

Introduction to ‘Between Head and Hands’

This text is an introduction to the Issue ‘Between Head and Hands’, a collection of texts by filmmaker and photographer Johan van der Keuken.

“When making my films, I always go through the same stages. The first is a kind of hunch, an idea about what the film should be – in other words, the reason I want to make the film, the need to make this very film now. This is always a fleeting idea, difficult to define, but already fairly complete. I’m then still at the level of imagination. One day you wake up very early and you have a kind of global idea in your head.”1

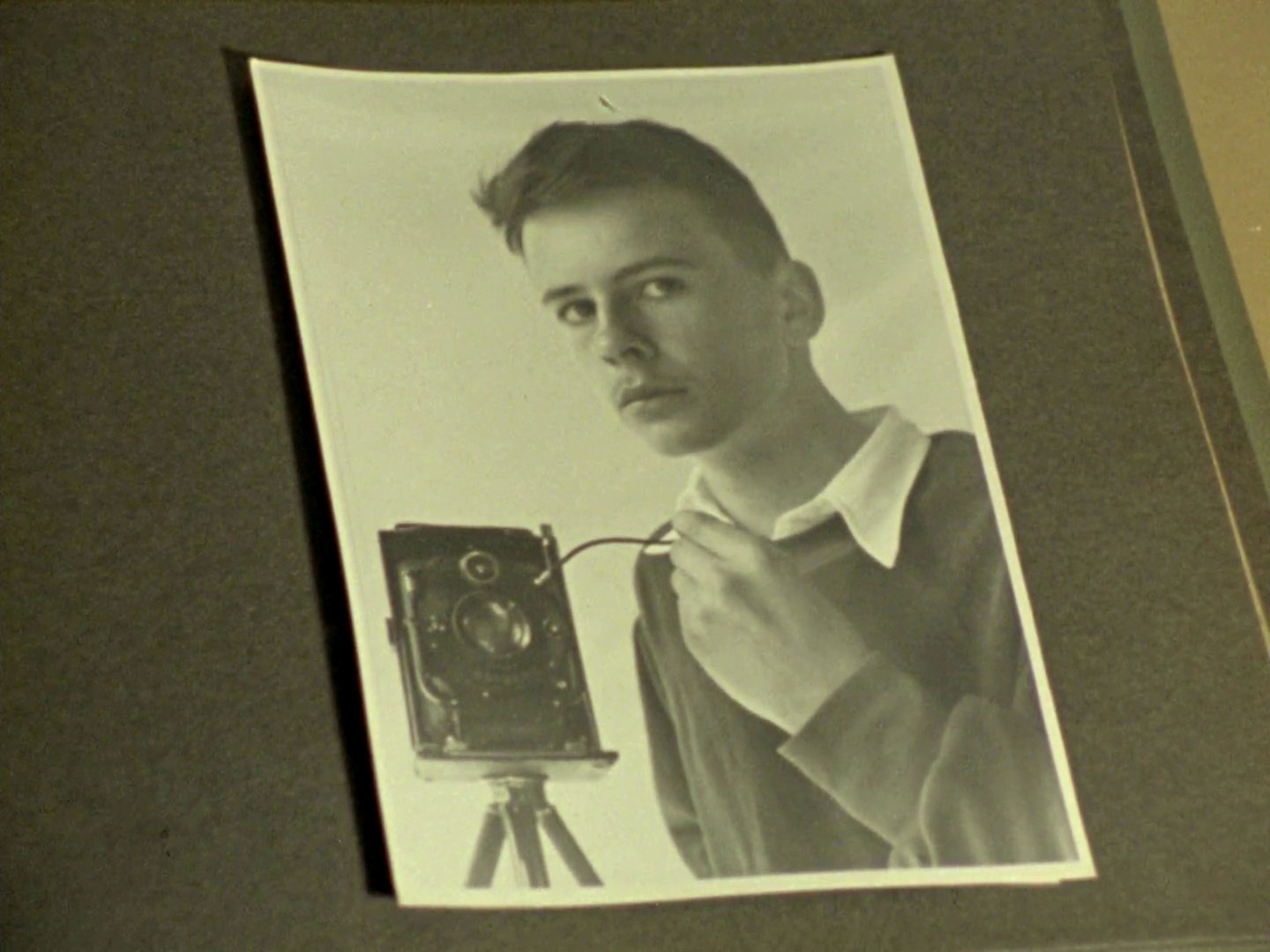

Johan van der Keuken (1938-2001) was a Dutch filmmaker, photographer, and author. At the age of seventeen, he already made a name for himself with Wij zijn 17 (1955), a photo book of portraits of peers. A year later, he entered the Paris film school IDHEC, where he discovered a growing passion for filmmaking. As a filmmaker, he broke through with experimental documentaries such as Blind kind (1964) and the North-South trilogy (Dagboek, Het witte kasteel, en De nieuwe ijstijd, 1972-1974) in which he depicted increasing global inequality. He made more than fifty films.

Van der Keuken’s cinema lives off the tension between ethics and aesthetics, between a radical commitment to the world and a distinct attention to form. The filmmaker stands radically in the world, looking through their lens, framing reality. A documentary filmmaker though, Van der Keuken said, can never pretend to represent reality. “For me, the material side of film comes first: a beam of light on a screen. And what is transmitted in that bombardment of light on a screen is always fiction.”2 Influenced by painting, he always calls attention to the matter of the medium itself through the conscious use of light, colour, and texture and a rhythmic, musical montage.

Van der Keuken was also a gifted writer on cinema, an activity through which he sought to delineate his practice as a filmmaker. Every filmmaker goes through a trajectory between the idea for a film and the final work. How that distance is covered, how to cross from that first stage – the “inner image,” as he called it – to the finished film, is different for each filmmaker. Writing played an essential role for Van der Keuken in this: “For myself, writing was necessary at times, because something lived inside of me, floated before my eyes, that I wanted to grasp. With hermetic formulas or intuitive stammering, speculative ebullitions or harsh prescriptions for the world.”3

Van der Keuken elegantly distinguished writing and filmmaking from each other. The two activities do not impose strict prescriptions on each other; rather, they run parallel in his work. They are similar searches but with different means. Early in his career, writing was a way to anticipate his films, to explore ideas that may not yet have fully manifested themselves in his work. “I suspected film for some time to be a thing in which time and space have fused and solidified, before I could really make that thing. In the meantime, I needed words to make the connection between my head and my hands.”4 While filming, he tried to forget his ideas. Or not completely: “You have to forget and not forget at the same time, but above all you have to be open to the situation itself.”5 The stammering, the formulas, and the harsh prescriptions are, “between the different situations and periods of filming,” still of crucial importance. “Writing is not my profession; it is an activity that links other activities,” he said.6

Van der Keuken wrote his texts not only for personal use. Countless texts of his were published in Dutch magazines and newspapers such as Kunst & Nu, Skrien, Algemeen Handelsblad, and Haagse Post. Texts in which he sometimes defends or explains his own films, but also writes about the work of makers he admires. In the magazine Skrien he long had a monthly column, “From the World of a Small Independent.” This ironic title pointed to his dual position as an engaged filmmaker: pleading for an equal world and at the same time constantly hawking his own artistic work.

In 1980, Zien kijken filmen, a first book with texts by Van der Keuken, appeared. Later, in 2001, an even more comprehensive edition followed: Bewogen beelden. Unfortunately, these books, and the texts contained in them, are hard to find today, and you often have to go to specialized second-hand stores for a copy. Hopefully this collection of texts by Johan van der Keuken offers a chance to (re)discover him not only as a filmmaker but also as one of the most original writers on cinema.

Gerard-Jan Claes, Nina de Vroome, and Tillo Huygelen

- 1Johan van der Keuken, “De fasen van het filmmaken,” from a conversation with Robert Daudelin on the occasion of the film retrospective in the Cinémathèque Quebecoise in Montréal, 1975. This excerpt originally appeared under this title in Zien, kijken, filmen. Foto’s, teksten en interviews (Amsterdam: Van Gennep, 1980).

- 2Serge Daney and Jean-Paul Fargier, “Een interview met Johan van der Keuken in de Cahiers du Cinéma,” translated by Johan van der Keuken and published in Zien, kijken, filmen (1980). Originally appeared in Cahiers du Cinéma 289 (1978).

- 3Johan van der Keuken, “Je wilt dat het altijd zo blijft”, in Zien, kijken, filmen (1980).

- 4Van der Keuken, “Je wilt dat het altijd zo blijft”.

- 5Van der Keuken, “De fasen van het filmmaken”.

- 6Van der Keuken, “Je wilt dat het altijd zo blijft”.

Images (1) and (2) from Vakantie van een filmer (Johan van der Keuken, 1974)

Image (3) from De grote vakantie (Johan van der Keuken, 2000)