The Mystique of the Camera

Message for Menno Euwe, Sound Man

How to return, how to leave behind. The cinematic space of New York, the Lower East Side, “Loisaida” as its Spanish-speaking residents so aptly call it and also write it: cracked pavement, the rot of bad teeth, manhole covers, the scars of flames, scorched spot in the city – now left behind, everything forgotten, senile like in Bernlef’s Mind Shadows. Suddenly you no longer know a single name, a single place, a single number; you have gone blind from too much seeing.

Yes, it’s true, shooting a film is a Work of Love. Endless love, grand indeterminable flow to and from people, energy and yearning. Endless shlepping with the camera and all the other equipment, the rolls of film and Nosh with the Nagra recorder and the microphones, the tapes and the light, sometimes on the verge of total exhaustion, not an unusual feeling for women, she says. Endlessly “pleased to meet you, everything nice, beautiful, impressive, too much, we would like to film how people survive and the money, how it flows, those who have it and those who don’t.” That is what we want to film, that is why we want to film you. Nice people! They are just nice, in other words very much alive, or dead, addicted, broken, down and out. Ever since Bessie Smith, there has been a whole down-and-out romanticism, talking about it, defining it, singing about it all serves to specify an inconceivable experience that then goes on to become a legend, and then folklore, and then a lie. An acceptable, operable form slips in between man and his truth. ‘Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out’, a song whistled between the teeth of the rich man as he spreads his behind over his bag of gold. A form problem with no solution.

The electricity of doing something in this city. All that complaining and whining in Holland, nothing ain’t ever really possible… Come on, go for it! Anyone can do anything. My world is an enormous belly, I swell up, and over that balloon I look at other worlds below me, as tiny as my insignificant toes. This here is my America and tomorrow I will vote for more and more, it never ought to end. The other me (the author) says: what about the other worlds that get less and less, and want it to end right now? What about the tension, the violence? But we too have been touched by that go-and-get-it spark, just like the little man who is a tough and strong man, a Puerto Rican or Dominican, who is against it all, that goes without saying, but he’s also enterprising, always on the lookout for business, he makes it or dies, he braces himself to stay where he is in his neighbourhood, his house tiny as it may be, at the foot of power and not to be smoked out and exiled over the bridges to Brooklyn and the Bronx. He estimates his own worth and the worth of his equals and acts accordingly. We are charmed by that active thing, it peps you up, it is refreshing, yes. It is just as if you are writing along with a 78 RPM record, those notes go too fast, have you seen the despair, yes, seen, but senile now, a menacing feeling, sometimes, walking into the twilight among groups of twilight people, on the stoops in front of scorched houses among piles of broken TV sets, more broken TV sets and injection needles.

When we film an arrest, voices resound from above the crowd of onlookers: “Hey motherfucker, get out of our neighborhood!” Petrified, the thought alone of a knife in my back is enough, I stop the camera just as one of the cops flicks off the hat of a little detainee, is there some more heroin under it? The most humiliating moment of all, I should have gotten it, remorse for that. Our guardian angel in Loisaida, Marlis, shouts up to the voices shrieking from the scorched windowsill above us: “Shut up, you bitches, I live here! You just moved in trom Connecticut!” Next time I’ve got to have the guts.

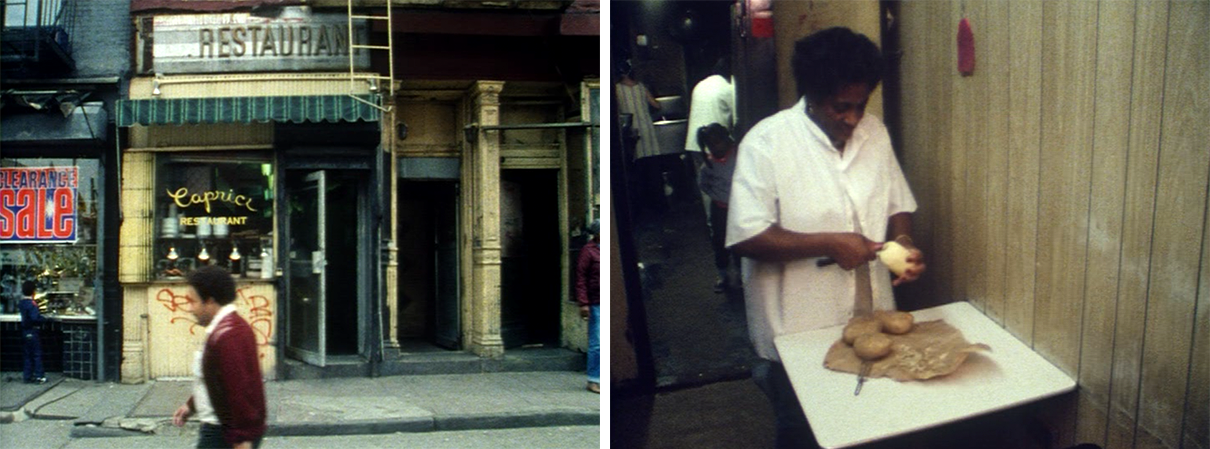

There is a mystique of the camera you have to obey. If someone is dancing and I am filming her, then I dance with the camera, I see the edges of the picture dancing with the edges of the person, that woman. Like Adela, an overweight but sturdy, shiny black woman, a scrumptious warm shy but very determined being. Dances on the sidewalk in front of her restaurant, Caprice on Avenue C, dances to the music coming out of the touching little model car contraption driven by a round-bellied Hispanic gentleman with a Panama hat and cigar, and the proceeds go to crippled Puerto Rican children – aiudales a caminar, help them walk again – and I dance along with the camera, just a few careful little steps and I hope it is barely noticeable because who can dare move in the presence of these master dancers: there is Adela herself and another woman from the restaurant, smaller more wrinkled, knowing, laughing, and the moustached man in his white jacket, also from the same restaurant, always silent but an elegant cavalier, a swinging, toothless, radiant old lady, cigarette dangling from her mouth, an introverted young girl at a distance swaying only slightly from the hips, a motley group of spectators, taking a sip now and then from a brown paper bag. Dancing with the camera with graceful precision – I know that Nosh is getting the sound right – she takes me across Avenue C, where the sound is now melancholy and distant. Italian neo-realistic. The dancers become tiny animated figures pasted against a flat housefront, the purplish reddish bricks, tin, iron, aged aluminium, yellowish paint, aged stoops, a decor with the letters Candy Store, Caprice and farther down the street, my favourite: Eddy’s Bakery Shop with the sugar-coated cake and the hope-filled bride and groom on top: Loisaida America Decor. No use holding back, go ahead and love it. The cinematic space you can’t forever keep untouched by references to older masterpieces – at the moment the barbarian Fuller is the strongest of all – but try to postpone them for a while, mistrust those references and peel down that image going back to the real-life despair and passion. Feelings that might be smaller and less classical but are at least within your own reach. Stay latent as long as possible. Be senile. Here I Stand. I’m Blind. Please Help Me, Buy a Pencil.

Bought a second-hand suit for the trip at Jojo’s on Herenstraat in Amsterdam and a tie too – had not worn one in at least 15 years – and off we go with a charming enterprising smile to financial backers, investors. I’ve already read a variety of books on money, but this is not the world of the Dutch economist Professor Heertje, this is the realm of Mark Motroni, Peter Bakstansky, Ed Kassakian, Roger Kubarych and Mike Kajanka with the icy eyes of a J.R. Those eyes give me the creeps; my tie is too tight. About money, the bloodstream, the clean killer, making something out of nothing, I think in silence and at a distance, covertly and in instalments, I don’t betray my thoughts to my unbiased thinking, waiting for the unexpected moment when the never-ending flow of info will be captured in a very everyday shot. Until that moment, I do not understand a thing. I make a composition out of the signs I pick up on the way. Signs that have eyes and a voice, received with a woman who is mistress and friend alike, in a space of flesh where I am happy, in a cinematic space where I am happy. A cinematic space between walls of radiant and innocent gas on which bodies and objects interglide in illumination. If it is rolling right and I am rolling with it, the camera is a string, an elastic string or a string of steel. When two men look, it is one thing. When two women look, it is something else. When a man and a woman look, it is something else again. Two eyes, Image and Sound, together make a third eye.

This text was originally first published in Skrien, Winter 1994-1995. This translation was made on the occasion of the retrospective ‘Through the Lens Clearly: A Retrospective Look at the World According to Johan van der Keuken’ held at MoMA in 2001.

Images from I Love Dollars (Johan van der Keuken, 1986)

With the courtesy of Prudence Peiffer and Josh Siegel