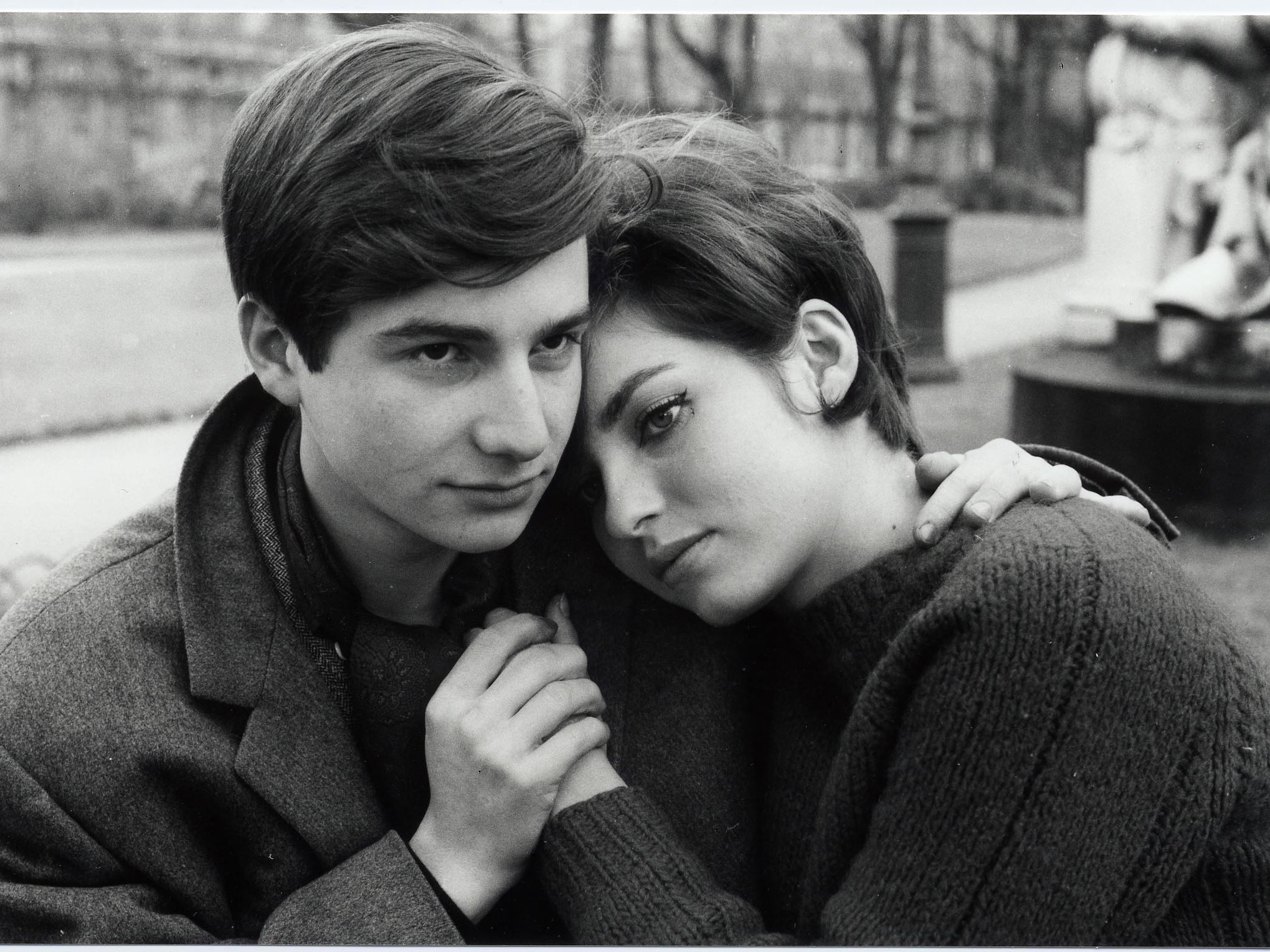

Antoine Doinel is 17, lives in a hotel and works in a factory making records; he loves music. He falls in love with a woman he meets at a concert. She sees him as a friend, but her parents love him.

EN

“Every Truffaut fan knows how staunchly attached he remained to a form of omniscient, thirdperson, novelistic narration – high on plot information and whimsical observation, delivered in a sly, swift, matter-of-fact way. This is part and parcel of his great formal economy. An example can be heard in his splendid short Antoine et Colette (1962): "Antoine and Colette met often and traded books and records. They discussed hi-fi over coffee and lemonade, and walked each other home, talking for hours on end in their doorways. Colette treats Antoine like a friend. He either doesn't notice or accepts it for the time being." In terms of sheer storytelling craft, Truffaut achieves here as elsewhere something exceptionally difficult in cinema: to convey the iterative, the things that happen in more or less the same way every darn day. But, for a more cinematic thrill, listen closely to the total soundscape of Antoine et Colette, its crisp montage of sounds and aural clusters: grabs of songs, specific everyday noises (clock alarms, pneumatic drills), classical music dwelling within a scene, then soaring beyond it. This little, thirty-minute film speeds by so fast, in fact, that Truffaut can instantly turn anyone into the narrator: Antoine tells the story of his week, Colette recalls a story. Such constantly displaced, insistent flow of show Bookmarks es helps give Truffaut's films their flavor of freedom and Iyricism.”

Dudley Andrew and Anne Gillain1

“Holmes and Ingram point out that, with the exception of his historical films, one usually finds in Truffaut “some self-referential tribute to the pleasure of watching and/or making films.” In Les 400 Coups, for example, we see Antoine and René skipping lessons and going to the cinema; the camera lifts up from street level to the sign “CINE” (in bold uppercase) as if to express the cinema’s literal ascendance (0:20:15), even eclipsing the film being shown, in spite of its lurid poster. The opening shot of Antoine et Colette is a familiar pan up from the street to the cinema on the Place de Clichy (0:1:41) before moving to Antoine’s flat.”

[...]

“despite the recurrence of movie theaters in Truffaut’s films, we seldom see any moving images actually projected in them. The newsreel footage that announces the result of a slalom while Antoine Doinel desperately tries to kiss Colette in a movie house (Antoine et Colette, 1962); the Nazi’s book-burning shown in the Studio des Ursulines where the protagonists of Jules et Jim (1962) happen to meet again; [...] are exceptional moments in that they are also actually shown to us.”

Dudley Andrew and Anne Gillain2