Vivre sa vie (The Story of Nana S.) by Jean-Luc Godard

At the beginning of this film, the camera inspects the backs of a couple sitting at a bar chatting. The wall of mirrors behind the bar occasionally reveals fragments of a male and a female face, though nothing guarantees that these are the faces of the people chatting. What is said is therefore by no means a trivial introduction; it is decisive for both characters.

This scene suggests an entire aesthetic programme. From the outset, it indicates to the spectators what is expected from them and what awaits them.

We are used to films in which image and language complement each other, in which one confirms the other as a deceptively similar imitation of reality. Dialogues are deployed so as to show either the speaker’s or the listener’s reaction, a dramaturgical procedure that, in relation to the characters, insinuates a permanent, absolute unity of external appearance and language and in which every utterance is an essential utterance, essential speech which provides information about the characters’ true being.

In Godard’s films, this interpretative combination of image and language that purports to capture the characters’ innermost being and give a complete picture of them, does not exist. It is made clear that language does not merely accompany the image. Rather, it is juxtaposed with the image as an independent, equally expressive element. Instead of the reassuring interplay of image and language to enhance the clarity of what is represented, in Vivre sa vie both what is represented and the means of representation are put into perspective by way of a constant dissociation of image and language. This separation also results in a double perspective: the perspective of the people represented and the perspective of the person who sees them. Godard’s camera keeps its distance; it registers. Godard refuses to impose an opinion on the spectator through dramaturgical manipulation. The verisimilitude of his art does not rest on faithful imitation of reality but manifests itself in the recognition of its fictional character.

The main effect of this process is a disruption of illusion. The spectators are prevented from succumbing to total fascination. They are made aware that they are not seeing reality but a film that shows aspects of reality, whose estimation of truthfulness is left to them.

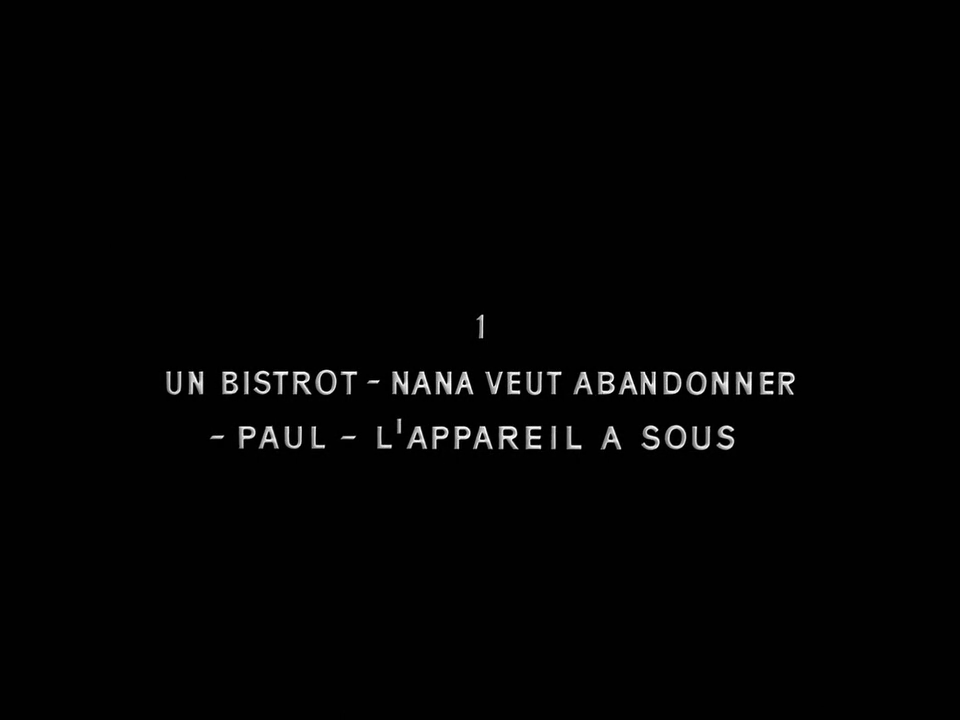

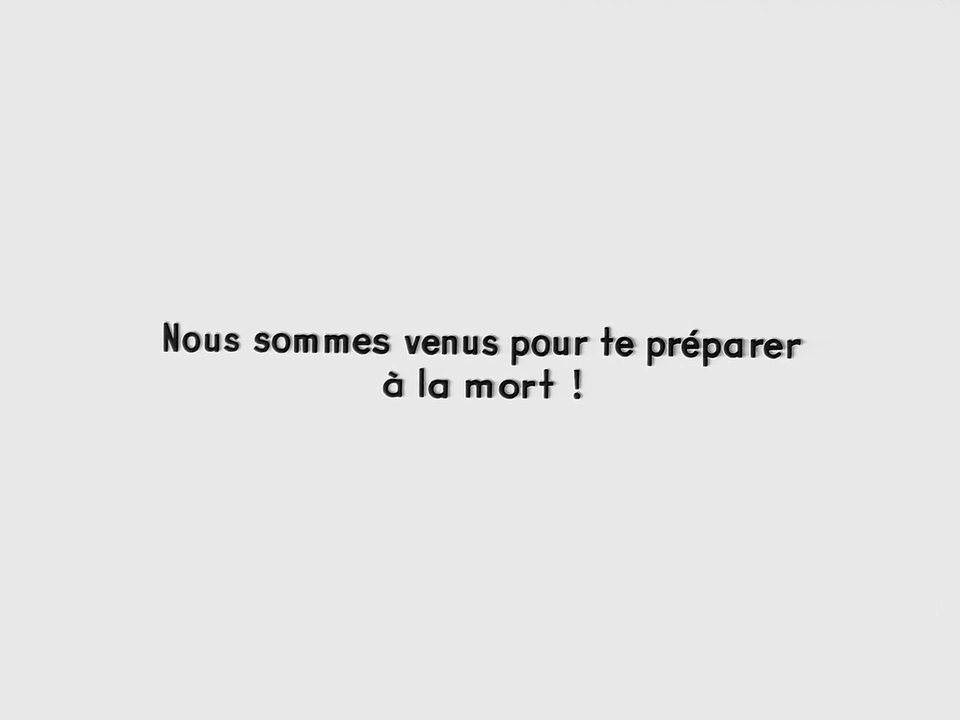

Furthermore, this separation of image and language shows that it depends on the medium through which aspects of a situation come to light. The division of the film into twelve scenes by means of intertitles is not just a means of hampering the narrative flow and pointing out that the film is not the story of a continuous development. The intertitles demonstrate that a linguistically formulated and written statement is a version of the reality depicted that differs from the representation through image and dialogue.

Such attempts at relativisation by Godard could be considered aesthetic skirmishes. But when he attacks the sign systems whose authenticity underpins our usual conception of reality, it becomes unmistakably clear that there is more at stake – namely, our very understanding of reality as mediated by forms. Godard combines his mise-en-scène of the work of prostitutes with statistical texts on prostitution. The double perspective thus created again makes it clear that the power of a statement about reality is independent of the objectivity of the means of expression. A comparable scene is that in the police office, when Nana puts her personal details on record. It is not disputed that these data are an aspect of Nana as a person. But it is no coincidence that in this very scene Godard has Nana say a slightly modified version of Rimbaud’s famous phrase from the Lettres du voyant: “I am an other.” Or when Nana measures her height in hand spans; the gestures with which she does so say more about her as a person than the resulting centimetres. She wants to attach her photo to the cover letter to her future employer. The letter says that she still has short hair but that it will soon grow back. She will certainly no longer look like Louise Brooks but perhaps more like Brigitte Bardot, just as Bardot in a black wig looks a lot like Anna Karina in Le mépris. Neither the fixations of appearance nor the appearance itself justify a definitive statement about reality.

There is a lot of quoting in this film. The quotations have mostly been understood as simple naturalistic comparisons, as interpretative or explanatory examples to substantiate the truth of what is depicted. A closer look reveals that they actually have the opposite function. Godard does not claim that Nana is like Joan of Arc or Porthos any more than he claims that Vivre sa vie is reality.

The pre-formed units of meaning that Godard inserts into his narrative are rather a kind of critical apparatus, variants of both the subject matter and the film’s mode of representation.

There is hardly any concrete reason to consider the school essay about the chicken a reduced, more-or-less distorted parallel to the film about Nana. Rather, it is a parody of the still ubiquitous essentialist separation of form and content. Godard never says that Nana preserves a pure inner self despite the filthiness of her external situation. Godard does not consider his character a mere symbol for some abstract quality. He takes his characters seriously in the way they are.

The serial the saleswoman in the record shop is reading, however, does have certain similarities with Nana’s fate in terms of content, but it is still a reflection on the aesthetic assertion repeated by this film in ever new forms: the credibility of the content only occurs through its form.

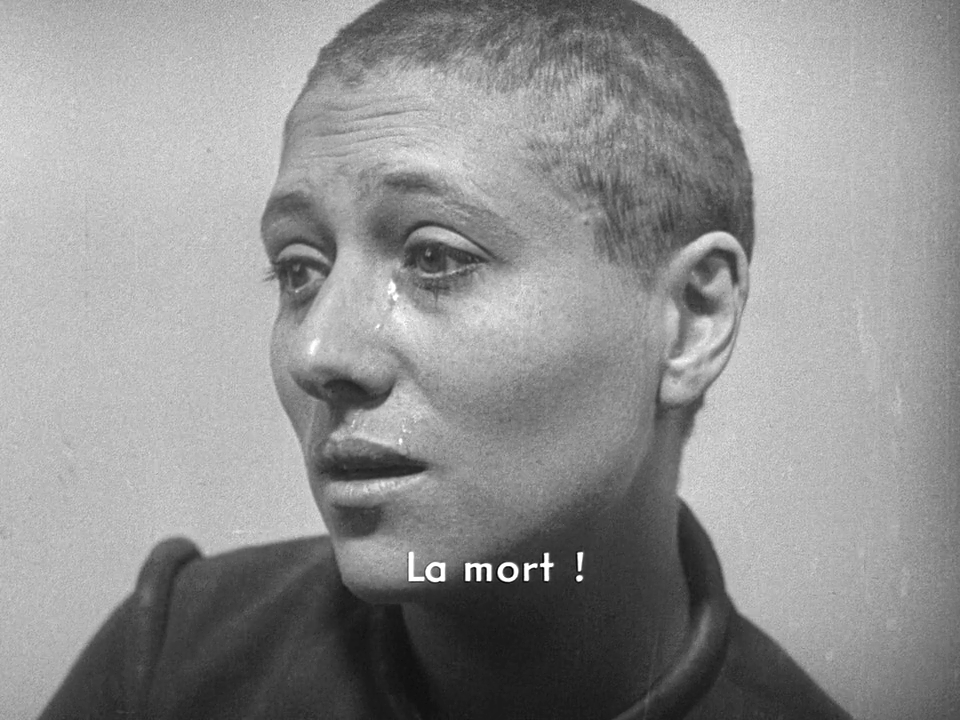

One sees Nana at a screening of Dreyer’s La passion de Jeanne d'Arc. Since both are young girls and both die at the end of the film, it occurred to some to claim that with this quote Godard wanted to elevate Nana to the status of a saint. Leaving aside the fact that Godard was obviously primarily concerned with the depiction of fascination and influence through art, if one does absolutely want to draw a parallel in terms of content, one could just as rightly claim that Godard is offering a historical variation on the theme of a woman’s freedom in a male society.

Nor is Poe’s story The Oval Portrait a comparison to what Godard himself does. It is a paraphrase of Godard’s concept of art. It is a mistake to want to grasp something, because that would be an attack on the freedom of reality; one must come to profit from things without grasping them. This is what Godard said in an interview with Jean Collet. Godard’s art is a detached art, both in relation to his invented characters and his audience. It presents itself at all times as something made, something that does not feel like a substitute for reality. This does not mean, however, that Godard propagates an art that has no relation to reality. It is precisely his technique of quotation that shows that, for him, art is not a form but a factor of reality that operates on an equal footing with other factors. Godard shows art in action. That is the meaning of the Poe quote or the Dreyer excerpt: art only comes about in the confrontation with people. He is not interested in what is elevated to the status of art according to changing standards and is gathering dust between two book covers or on a strip of celluloid.

Godard’s concept of art is perfectly relative. When he shows the effects of art in his film, he leaves no doubt that, in his view, they depend on individual disposition. Nana is deeply moved by the Dreyer film, her neighbour hardly at all; the painter is decidedly more fascinated by the Poe novella than Nana; the philosopher is impressed by the Dumas story, while Nana doesn’t quite know what to make of it.

The relativisation of art, however, has nothing to do with a cheap scepticism. Rather, it is a kind of humanisation. Art thus appears as something man-made, as something temporal. Godard strips it of the numinous veil woven around it by those for whom artists are still blessed by the muse and who still consider art to be otherworldly.

Godard by no means considers himself an original genius; his technique of quotation proves this. He practises the method that Brecht believed suited our times and which he described as a collective method that brings together all experiences and uses what has already been achieved in order to arrive at an increasingly precise and powerful description of reality. Godard’s film may consist of 90 percent quotations, but what do we hope to learn today from buildings that can be built by one person? This, too, comes from Brecht, from one of the Keuner stories entitled Originality.

This piece originally appeared as “Vivre sa vie (Die Geschichte der Nana S.) von Jean-Luc Godard,” in Filmkritik 6, no. 11 (November 1962): 511-516.

Images (1), (2), (3), (4), (5), (6), (7), (8), and (9) from Vivre sa vie: Film en douze tableaux (Jean-Luc Godard, 1962)