A native of Mauritania is delighted when he is chosen to work in Paris. Hoping to parlay the experience into a better life for himself, he eagerly prepares for his departure from his native land. Although an educated man, he has extreme difficulty finding work and an apartment. He sees racial inequity as blacks are relegated to manual labor while less skilled whites are given preferential treatment. A dinner with a liberal white friend even reveals a continuing attitude of colonization towards third world countries. The disappointed man runs off to the woods where he hears the far off cry of the jungle drums calling him home from a cold and indifferent land.

“God is surely a white man.”

“Unless he’s a negro.”

“Well if he’s a negro then he’s the biggest bastard the world ever invented.”

D’origine mauritanienne, Mohamed Medoun Hondo Abid, dit Med Hondo, est né le 4 mai 1936, à M’raa une oasis saharienne. Après des études dans une école professionnelle marocaine. Il s’embarque un beau jour pour le pays de ses ancêtres les Gaulois.

S’étant initié au cinéma en voyant film sur film, il tourne deux courts métrages en 16 mm, noir et blanc : Ballade aux sources et Partout ou peut-être nulle part.

C’est sans un sou qu’il commence le tournage de Soleil Ô en 1969, avec des amis qui acceptent de travailler en participation. Le devis de ce film de 98 minutes ne s’élève qu’à 18 millions d’anciens francs : les frais de pellicule, la location de la caméra 16 mm (le film a été gonflé en 35 par la suite) et du magnétophone Nagra. Le tournage dure une année.

Guy Hennebelle : Med Hondo, pourquoi Soleil Ô ?

Med Hondo : S’il me fallait définir ce film en un seul mot, je dirais : c’est un vomissement ! Ce qui m’intéressait, ce n’était pas de faire du cinéma, c’était d’exprimer, de crier, de hurler la révolte du Nègre que je suis. Même si j’avais été certain que le film resterait sous mon lit dans des boîtes, je l’aurais fait. Il fallait que je me libère de la réalité oppressante que je m’entourait depuis dix ans que je vivais à Paris. Ce qui m’a guidé prioritairement dans la réalisation, c’est le souci de traduire la réalité intérieure de mon héros problématique. J’ai horreur du « nombrilisme » dans lequel s’enferme une grande partie du cinéma français. Moi, si je fais du cinéma c’est pour dire quelque chose.

La plupart des film africains réalisés à ce jour restent prisonniers d’esthétiques relativement traditionnelles. Soleil Ô, au contraire ; manifeste une profonde originalité.

L’essentiel pour moi était de trouver le meilleur moyen d’exprimer ce que j’avais à cœur, ce qui me pesait sur le cœur. Je tenais absolument à ce que Soleil Ô soit un film violent. J’ai cherché à faire partager par le spectateur le sentiment du héros : il débarque en France et le voilà bombardé de toutes partes par des événements qui constituent autant d’aggressions.

Guy Hennebelle en conversation avec Med Hondo

« Toutes les scènes partent de réalités. On n’invente pas le racisme, surtout au cinéma. On ne l’invente pas. Ce sont des choses bien précises que vous subissez et que vous enveloppent. C’est une espèce de manteau qu’on vous met dessus et avec lequel vous êtes obligé de vivre. Toutes les scènes un peu anecdotiques, même celles qui sont poussées à l’extrême, partent d’une expérience vécue.”

Robert Liensol

« Réalisé en France par Med Hondo et les acteurs de théâtre noirs fixés à Paris, Soleil Ô me paraît le film qui jusqu’à maintenant exprime le mieux l’Afrique. Est-ce paradoxal ? Pas tellement. L’éloignement, la nostalgie du pays, l’identité qui se confirme face à d’autres (à nous autres) qui sont différents et se jugent supérieurs doivent logiquement renforcer non pas un Africanisme archaïque et verbal que Med Hondo refuse, mais une Africanité globale (aussi bien, les acteurs proviennent, de tous les coins du monde noir) aucunement anecdotique. Et l’exil doit favoriser aussi le côté visionnaire que développent certaines partie du film.

Mais en outre ce film est un regard sur nous dont nous avons besoin, un regard fier, un peu âpre quelquefois, mais nuancé par l’humour, sur notre comportement à l’égard des Noirs, dans la vie de tous les jours à Paris, un regard sur notre civilisation de gaspillage qui est juste, mais qui est plus perçant venant d’hommes qui leurs origines rattachent aux domaines de notre pillage et (avant ce pillage) à une sagesse, une intimité dans les rapports avec la nature que nous n’avons guère connue à ce point dans toute notre histoire.

Il n’est pas sûre que dans son mode d’expression très personnel, Soleil Ô, plaise à tout le monde, mais il est sûr qu’on doit le voir si on s’intéresse soit au destin de l’Afrique, soit au cinéma. »

Bernard Tremege

“Soleil Ô, a title that owes allegiance to the old song of African slaves en route to the West Indies, sung to express indignation over their abrupt disengagement from their native land, is Med Hondo’s first feature-length film. Described by the maker in the opening sequence as a ‘pamphlet,’ this film meticulously attacks foreign imperialism in Africa from slavery to the present. It is this colonial-neocolonial paradox that provides the core of Soleil Ô’s complex structure. In it we see a tapestry of history fashioned as an avant-garde essay on racism and the intense sense of estrangement and alienation to which Med Hondo and entire black immigrant communities in France are subjected.

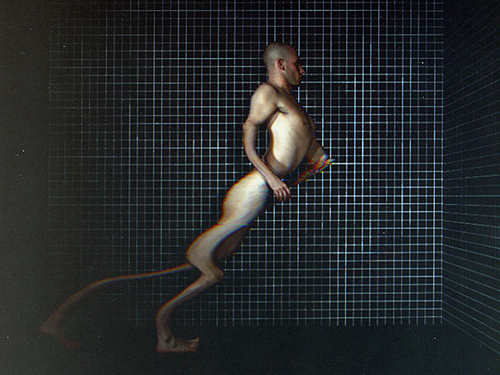

“I make films,” Hondo said, “to show people the problems they face everyday and to help them fight those problems.” Soleil Ô begins with an animated sequence of an African puppet ruler being catapulted to power by foreign military intervention only to have his reign terminated by the same people who installed him. From here, the film’s subsequent episodes revolve around a young African immigrant, an accountant, whose experience Hondo uses to dramatize the frustrating existence of numerous other black immigrant workers (Africans and West Indians) living in France. The accountant goes through unprecedented humiliation as he faces racially motivated rejection looking for a job and accommodations; even when he does menial jobs, cold attitudes greet him. As he meanders through dehumanizing settings, indicative of living conditions for blacks in France, Hondo synthesizes contradictory vignettes of colonial and neocolonial life suggestive of Africa’s relationship with France. Subjected to anguish, mental torment, and internal conflict, the accountant is forced to reflect on his conscience, seeking solace in a hospitable enclave where social and political actions for self-determination and liberation are preferably contemplated. The last segment is a meditative sequence with glimpses of superimposed images of martyred revolutionaries (Patrice Lumumba, Che Guevara, Malcolm X) shown as cultural metaphors reminiscent of Fanon’s concept of returning to one’s roots.”

Nwachukwu Frank Ukadike

“This questioning of aesthetics as a benign sphere without political ramifications is also questioned as a means of distancing the viewer from the visceral impact of depictions of suffering and oppression and figures as another aspect that Third Cinema brings to its criticisms of mainstream media practices. The latter’s slick, almost parasitical use of debilitating images of a suffering that takes place elsewhere (‘blood of others flowing from the television’) can be contrasted to such directors as Med Hondo when, back in 1978, he offered that ‘to depict the objective reality of people… we must live it in the first person’.”

Howard Slater

« Au-delà de ses défauts de constructions, d’un style souvent chaotique et de passages a vide, Soleil Ô s’impose à l’évidence : rarement première œuvre aura offert une telle impression de force, de bouillonnement, de richesse de témoignage. Moins européen que Désiré Ecaré, d’un humour moins feutré, moins soumis que Ousmane Sembene aux pièges tendus par le néo-réalisme, Med Hondo a réalisé un film dérangeant, qui laisse une brûlure sur l’esprit. Soleil Ô est un film primitif au sens noble du terme comme pouvait l’être, au Brésil, Le Dieu Noir et le Diable Blond [Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol] auquel, par bien des aspects, il faut penser : c’est en effet la même rage d’attaquer, de dénoncer, d’aller jusqu’au bout de soi-même que l’on trouve dans le premier long métrage de Hondo. A travers le portait et les mésaventures d’un Noir qui débarque à Paris et se heurte d’abord à l’indifférence puis au racisme des Français, Hondo s’attaque à un système, à une façon de voir, de comprendre, à une morale. »

Positif

« Très riche sur le plan thématique, Soleil Ô est d’autre part d’une facture esthétique remarquable. D’emblée, l’auteur a su dépasser les styles souvent surranés dans lesquels d’autres cinéastes africains piétinent encore. Sa mise en scène est délibérément moderne, sans être pour autant d’inspiration occidentale. Tout au plus, peut-on lui reprocher le recours intermittent à quelques tics du théâtre dit d’avant-garde. Le mérite de Med Hondo est, fondamentalement, d’avoir su combiner avec beaucoup d’intelligence, le « discours » didactique et la « représentation » spectaculaire.

On notera aussi l’importance de la bande sonore, le plus souvent en étroit rapport dialectique avec l’image. Deux exemples : après avoir discuté de leurs conditions d’existence en France, divers Africains concluent par intermédiaire du commentaire en voix off qui rien ce chargera jusqu’à ce que … On entend alors un déclic et l’on voit surgir une lame de couteau libérée de son cran d’arrêt. »

Guy Hennebelle

“It was purely by chance that we ended up being artists ‘of colour’, as is the term usually used. In Paris together for basically the same reasons, Bachir, Touré, Robert and I found ourselves right in the middle of a country, a city, where we had to get by, for a lack of better words, where we had to work: being an actor, a musician, a singer. And where we realized immediately the doors were closed […]. As a solution we thought of creating a theater group and, in the meantime, we all made Soleil Ô. In order to make the film we had to overcome every bureaucratic and material obstacles, in other words, find a producer and tell him: “It’s the best story around, because we believe in it”. Like they say: “If you’re good at talking, you’re good at making film”. And so, we made Soleil Ô without money […]. All the scenes were based on reality. Because racism isn’t invented, especially in film. It’s like a kind of cloak put on you, that you’re forced to live with. Even the confession scene, at the beginning: in fact, in the Antilles, where I was born, they taught children that knowing how to speak Creole was a sin to confess.

I know that the cinema you called cinéma-vérité has always avoid saying things of the kind. The only thing it has done in this sense is take black faces and mix them in the crowds. To demonstrate that as the West continues to expand itself economically, the more it will need black labor. And so Africa will always be an underdeveloped continent: saying the contrary is a lie […].

The original idea was to show tourist spots packed with blacks only. All of a sudden you would see Sacré-Cœur, and you would see only blacks. It would have had a powerful cinematographic impact. But the idea remained on paper and wasn’t translated into images.”

Med Hondo

“So we return to the necessity of knowing what we want to say, and to whom we have to say it. For what public has learned to read, to decode a film? An elite public. But there are other publics. Film criticism does not play its role, or rather, it plays it too well. The handful of critics we know whom I will qualify as “progressive” must then fight in place of all the others. They have no right not to be present, they must reject demagogy, paternalism, quasi-journalism. For if they desert, what remains? Criticism as practiced in the columns of the right-wing press does not interest me. My relations with progressive critics have never been negative. I must say it is thanks above all the western press, especially the French press, that the films which have been seen have been available, an that Africans have been informed about them. For sure, with some inadequacies on some people’s part, but without undue paternalism. Criticism’s influence on the conscious public, on the distributors, is an essential and often decisive support. It is very encouraging and positive that our films are taken into consideration, that they are dealt with on an equal footing, and so with the same rigor as all the other. Sembene, Tawfiq Salah, I myself and many other have been put into the festivals and some theatres thanks to some critics, whose initial battles were sometimes with their own editors.

For me the country where for over ten years film criticism has never yielded up its responsibilities, is France. I don’t forget that Soleil Ô came out in a 64-seat theatre because the critics fought to find a screening space when so many owners were indifferent or suspicious. Today, when an American distributor or journalist wants African films (a rare occurrence), he telephones or writes to a French journalist: it is significant, all the same.

That said, an African film criticism is indispensable. At the present time, very few critics can express themselves in our countries, and they only have a very relative power (to inform, that is) on their national, even local level. The lack of a film criticism is not Africa’s special privilege. But it is a historical given that western film criticism is, today, the only one capable of reviewing our attempts; of informing the public and helping us; of studying and reflecting on African and Arab cinema. We, as African filmmakers, must ourselves invent, in our own, the film language to be spoken to be able to be understood, one day by our brothers. You are witnesses. On this account, you must not make out that our actions are in accordance with our ideas when it is not true. I mean that one does not have the right when defending progressive intentions, when one is a creative artist, a theorist, a critic, to produce or defend a consumer cinema. The public has to be awakened, or re-awakened. That demands courage. A leftwing (or so-styled) filmmaker or critic, then, is only doing his duty; we don’t have to award ourselves “medals.””

Med Hondo