This simple moral tale seems to prefigure Where Is the Friend’s House? Two young schoolboys, Dara and Nader, are friends until Dara returns Nader’s notebook torn and Nader retaliates in kind, setting off an escalating battle that leads to destruction of property and physical injury. In the second solution, Dara realizes his offense and repairs the notebook, preserving the peace and the friendship. The film is shot mostly in close-ups, with a narrator drolly chronicling the action.

EN

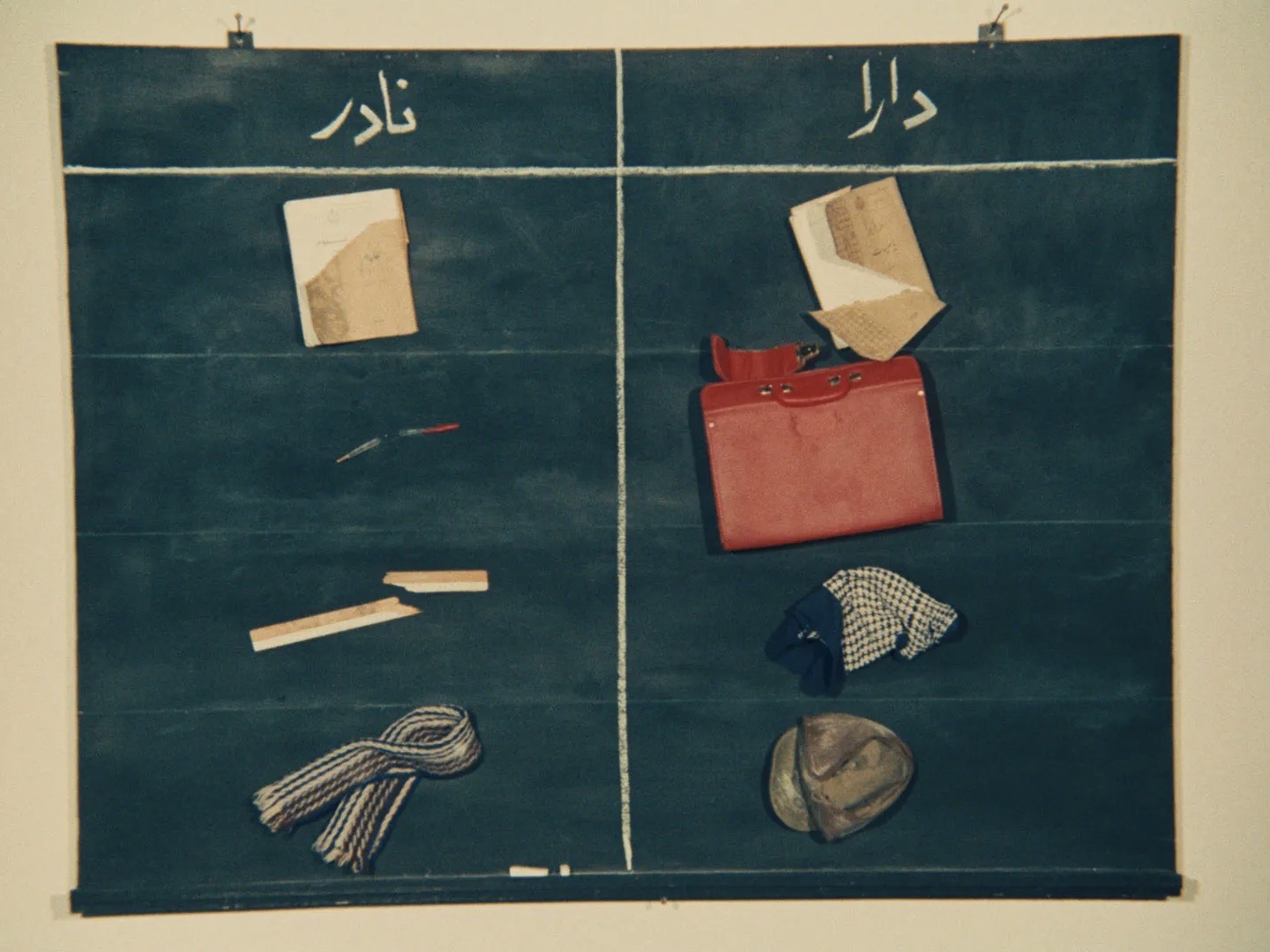

“Two Solutions for One Problem [...] shows what happens in a classroom after Dara borrows a book from Nader and returns it with its cover torn. The film is like a deadpan, Bressonian restaging of one of Laurel and Hardy’s epic grudge matches: Nader tears the cover of Dara’s book, Dara breaks Nader’s pencil, Nader rips Dara’s shirt, Dara breaks Nader’s ruler, and so on, in syncopated time. An animated two-column chart on a blackboard chalks up whose objects are destroyed; then the story begins again with Dara gluing back Nader’s book cover, the bell ringing for recess, and the boys exiting as friends.

A recurring formal principle of parallelism in these Kanun documentaries anticipates some of the repetitive elements in Kiarostami’s later features, such as the successive takes of the film being shot in Through the Olive Trees (1994) or the many drives up a hill to speak on a cellular phone in The Wind Will Carry Us. Some of these elements are even repeated from one feature to the next, such as the extended and extreme long shots concluding Life and Nothing More . . . and Through the Olive Trees [...], which are already anticipated in certain shots toward the end of Report. What I have in mind is a certain kind of construction in which a repeated shot, camera setup, narrative situation, or editing pattern structures the film as a whole. Children imitate the movements of other creatures in matching shots in So Can I; postrevolutionary authorities of various kinds comment on the same classroom dilemma with two different outcomes in Case No. 1, Case No. 2; contrasting forms of behavior, as seen and as filmed, are the subject of Orderly or Disorderly; and the drivers in Fellow Citizen are usually filmed from the same angle with a telephoto lens, recalling some of the documentary strategies in Tati’s Trafic (1971).”

Jonathan Rosenbaum1

“Kiarostami has not always been successful in keeping clear of the potential pitfalls that threaten his carefully balanced distance between reality and its undoing. In Do Rab-e Hal bara-ye yek Mas’aleb (Two Solutions for One Problem, 1975) [...], we see him falling victim to one of the most dangerous threats to his cinema: moral sentimentalism. By and large, Kiarostami has controlled this threat and kept it at bay with remarkable ingenuity – perhaps intuitive, perhaps cultivated, one can never tell, and that is a powerful aspect of his cinema. But in Two Solutions for One Problem we see what a slippery road Kiarostami has traveled. Two classmates face the dilemma of one of them having inadvertently torn the other’s notebook. With the first solution, the ‘victim’ would have his revenge but he prefers the second, his cooperation with the ‘perpetrator,’ which resolves the problem and preserves their friendship. Oddly enough, in retrospect, one develops a greater admiration for Kiarostami’s cinema when one notices such occasional setbacks. For it is in films like Two Solutions for One Problem that one sees the relentless pursuit of a cinematic language in which Kiarostami emerges triumphant. Despite its structural failure and its aesthetic collapse into moral sentimentalism, Two Solutions for One Problem still bears the marks of the same type of experimentation in uncharted realms of sensibilities. What Kiarostami questions in this film – the nature of revenge as a human trait, one of the most enduring features of human hostility – he approaches through the perspective of children. Kiarostami has always sought to experiment with alternative modes of progression from identical moments of crisis. In a sense he is trying to recapture moments in cultural infancy in which tension and aggression have resulted in a particular course of action, while other modes of response have been left perilously unattended.”

Hamid Dabashi2