La captive by Chantal Akerman

This is an extended version of a lecture held by Eric de Kuyper, co-writer of La captive (Chantal Akerman, 2000), at the cinema of the Deutsches Filmmuseum in Frankfurt on 1 November 2018, before the screening of the film.

Before the Screening

Before I start, let me say this:

No artist, no creator is able to analyse his or her own work.

Of course, there are many artists who pretend to be able to evaluate their work.

Don’t trust them.

So, I will not be able – as a cowriter – to analyse La captive for you.

What I can do is to tell you about … what happened in the kitchen.

*

What always astonished me:

Is it not very strange that in the case of such a visual medium as film, written words are always playing such an important – indeed decisive – part?

Words, words, words … all the time. From the very beginning till the very end: A movie must be presented, accompanied and explained by words.

Starting from this horrendous thing – a pitch!

Another horrible thing is what is called MOTIVATION.

Why does one want to make this film? And how? What’s this film about? Et cetera … words, words, words to explain things a filmmaker (or a writer, or any artist) cannot explain.

Anyhow, we have to do it. Have to?

Why all these words and explanations of something which does not yet exist?

(Well, it may remind you what the philosopher J. L. Austen said in his famous How to Do Things with Words.)

After it, when the film really exists, of course, more words and more explanation. I noticed that Chantal Akerman, who had to talk a lot about her films, used to answer very often HOW when they asked her WHY! And the contrary, when HOW she made that film, she answered WHY!!!

The most crucial part about all this writing of words is: the script…

Rare, very rare are the feature films made without a script.

The script is necessary for the shooting.

But long before there is a shooting, a script is already in the vital process leading to the making of this peculiar movie.

The script must convince producers, the institutions who give you grants, the actors, the whole team…

*

Officially I have been a cowriter for four and a half scripts for Chantal Akerman.

Two of these scripts were never made into a film:

– One was the very ambitious project of The Manor and The Estate, based on novels by the Nobel Prize winner Isaac Bashevis Singer about Polish Jews immigrating to the USA.

– The other was an adaptation of two novels by Colette: Chéri and La fin de Chéri.

Of course, the novels by Colette would be situated in a contemporary setting (as is also the case of La captive). But more interesting is that Chantal wanted very much to adapt the second part too, La fin de Chéri, which is not so well known and popular as Chéri. It is a quite bitter, sad novel. We hoped to cast Catherine Deneuve…

However, we discovered too late that the rights for all the works of Colette were blocked by the Americans.

And indeed, soon after – well a few years later – there was a Chéri by Stephen Frears (2009).

A film, of course, Chantal and I disliked very much.

Another script we never finished was Patricia Highsmith’s novel The Price of Salt…. we did not find a satisfactory way to end our script.

And later when I saw Carol by Todd Haynes, I did not appreciate the film very much. I had the feeling that Haynes did not solve the problem we had with one of the main characters: the child. However, Haynes did not seem to be bothered by it, and accepted the Highsmith plot as she had proposed it in her book.

About the “ending” of a film, I will have to come back to it, when I will talk about the ending problem of La captive.

So that’s for the “half” script by Akerman/de Kuyper.

*

Officially credited… This in film language is something very ambiguous. We should never totally believe the credits!!! There are, as you know, many false or pseudo credits in Hollywood movies made during the McCarthy period in the United States.

But movie making is always a team working… and especially in commercial movies the creative process is sometimes very difficult to reconstruct. The most spectacular example being Gone with the Wind.

So, I am credited for films I was not involved in – for example, Je tu il elle! But on the other side, I remember working a lot for Les rendez-vous d’Anna. With Chantal I discussed elaborately about the project and the casting, and I was her location scout in the Rhein-Ruhr region, which I know better than she did.

Anyway… for sure, I wrote with Chantal the script of La captive.

*

But let’s be a little more precise: What is a script?

It’s a written document with the first most important purpose: to convince a producer and or a committee who give grants for films to agree that this script should be made into a movie! The definitive movie, however, can be identical with the script, or different from it or partly different.

I remember the following in the case of Jeanne Dielman, that Chantal wrote a script, sent it to the Belgian institution, the committee who give grants, and the grants where given to her.

I remember Chantal climbing the staircase of my place rue Crespel shouting, “I got the money!”

When she arrived on the landing (not even entering my rooms), she added, “But I don’t want to make this film. I don’t like the script.”

And she told me how she would like to make it instead; she told me more or less what became Jeanne Dielman.

I must say now that I am proud I agreed with her that the script was quite average and that I told her she should make what she was telling me… I did not really grasp what she wanted to do… but it seemed to me quite daring, and not at all average.

Then I disappeared from the picture…

*

Anyway… interesting also is the fact that the people who give you the money on the basis of this particular script, most of the time, are not the same who, when the film is finished, compare the movie with the original script.

A script is just a script… and a movie is not the visualization of a script. In the case of Jeanne Dielman, this makes the difference between what could have been an average movie and the masterwork which Jeanne Dielman became.

*

So why Proust?

Chantal was a great reader of novels. She really enjoyed reading… When I met her when she had just finished her first film, Saute ma ville, in 1968, I must say that I was astonished that she had no film culture whatsoever. On the contrary, she had an impressive knowledge of literature. But then living in Brussels near the Cinemathèque, we went to see as many films as possible. And of course, some time later, living in New York and Paris she became a real moviegoer.

Strange for me is that she never mentions the German experimental films we saw in, for example, Oberhausen. Especially, the Hellmuth Costard film… Die Unterdrückung der Frau ist vor allem an dem Verhalten der Frauen selber zu erkennen from 1969. In this film a man is doing the household chores Jeanne Dielman will do later in Akerman’s film.

(Correction: in one of her carte blanche programs she chose Werner Schroeter – and especially his 8 mm Maria Callas films we saw in Cologne.)

But back to Proust…

When I met her in the late sixties, she already told me and advised me to read À la recherche du temps perdu, which I did then a few years later. (Well: I started it… Nevertheless, I read it completely some years later, in the early nineties, actually just before Chantal asked me if I would like to work on a film after Proust.)

I think it was a good thing, not to try to adapt the whole of À la recherche…

But I was a little disappointed, when we met for the first time in her flat in Paris, that she wanted to focus only on the relationship Marcel/Albertine. (My own favourite parts of La recherche… are the first volumes.)

But of course, I understood very well why she wanted to make a movie around this relationship. One of the reasons was that we both liked Vertigo and Marnie very much, and I think that’s the reason why – from the start – it was out of the question to set La prisonnière/La captive in the Belle Époque, in a historical setting!

She was – as she admitted openly – afraid of historical contexts. It was something which annoyed her in the Singer project, which was of course due to be in an historical context. She had no feeling for historical costumes, settings, props etc. Actually, she was afraid of making a historical film. And in a way I think – except for the main reason that the production of the Singer films was very difficult and at the end, did not have a positive end – there always was at play her doubts about “how to visualize” the past… For her, the subject of a movie – fiction as well as non-fiction – had to be in the present.

We didn’t think for a moment about making a Proust in historical costumes and setting. And I think we did not even take it into account because the “model” Hitchcock was so present from the beginning.

And I must add: As far as I remember, there was never a moment where – for one or the other detail – we could not see it as a contemporary subject!

I remember also that she admired very much Une femme douce by Bresson, a contemporary adaption of a novel by Dostoevsky.

*

So, her reading of Proust was very simple and direct: She went directly, she jumped in the richness of the Proust novel to what was the essence of “Akerman” – or would-be Akerman. (She had a very logical mind, even structural. At the time we – Emile Poppe and myself – were writing our PhD for Greimas, extremely arduous logical-semantic thinking. We stayed at her Parisian place. She read our stuff, and I was amazed how “intuitively” she understood it.)

In a way, and she said it also, “Marcel, c’est moi,” Meaning more the writer Proust, I think, than the character in À la recherche. She felt intimate with him.

Two impressions about the writing:

It was easy,

and it was a great pleasure.

Choosing and selecting the parts in the novel which interested us for the film, was totally unproblematic.

And re-writing Proust was … a délice.

We were both astonished how good and efficient the dialogues were – I never heard before that Proust was a master in writing dialogue. But there they were… perfect. And if not totally fitting the scene, it was a great pleasure to re-write Proust. To cut a phrase, to add another one, to make necessary junctions…

Let me add this:

Chantal and I have this point in common: we are more interested in “drama” than in “plot.” And more precisely the emotions, that’s what I mean with “drama” – the story and the plot are subsidiary.

Which in this case helped us a lot.

*

As always, we worked “part time” … In the morning, after letting out the dog, we discussed for one hour or two. Smoking a lot and drinking at lot of good coffee. Then we were getting hungry. In the afternoon or evening, Chantal wrote what we had discussed in the morning.

And then the next day, again in the morning we read what she had written the day before, – always scenes with dialogue – before getting on with a new scene.

Interesting to know is that I never wrote a word. I was not allowed! Chantal did the writing, well the first draft, and then I could correct, add, propose other ways of saying, or adding one or the other detail…but never writing it.

It went always in harmony, but the writing was her private part.

I was more or less like a coach. Trying to stimulate her imagination, always in a strict Akerman way! Which is always the way I work as a co-writer, and also the reason why I never go to a shooting. On the set I am afraid to see the things as a film director, in writing a script I am conscious that I am not, and will not be, the director.

Maybe strange, but for all her feature films, as far as I know, the writing was very central in her filmmaking. For her feature films, she had to write it very precisely, and then, after it, at the shooting she could feel free. It was already written; she must have felt safe.

On the contrary with her non-fiction – like Sud (about the south of the US) or De l’autre côté, (about the Mexican border) who were made around the same time, she did not feel the necessity to write… as a documentarist she liked to be as free as possible. And her producers – mostly Arte at that time – were happy with a “one-page” description of the documentary she wanted to make ... with of course a small budget.

I notice this difference because I worked on several projects of the Swiss filmmaker Jacqueline Veuve. She was a very prolific documentarist filmmaker. And before every film she studied and read without end about the chosen subject (may it be the Swiss Army or the Salvation Army). During the shooting however she forgot what she had prepared so conscientiously … Well of course, she was an anthropologist who worked also in the beginning of her career with Jean Rouch.

*

It was Chantal who changed the original title from Proust: La prisonnière became La captive. Albertine is only metaphorically “a prisoner.” But she is “captivated” – also in the sense of “fascinated” …

*

The script as it was written, was quite faithfully shot like that, without much alterations.

Two exceptions:

- One scene with Aurore Clément I quite liked was not shot (Chantal told me due to budget-reasons)

- Another one was added… It is a scene, I have to confess, I do not like very much.

And I think the “virtuality” of the script was wonderfully “realized” in the finished film.

Which is not always the case:

For instance, the next script I worked on with Chantal, Demain on déménage, was, in my opinion, not satisfactory realized in the movie. For one thing: the script was funnier than the film. One of the reasons was that at the time of the shooting Chantal had serious health problems. And, as I have also experienced, it is very difficult to find a “light” touch, when the shooting is very difficult. She was in bad health at that time, and one must say that Demain … is not her best film. A pity, because I think the script was good, much better than the film.

*

As always, we talked a lot about casting. And often I was a little surprised by her choice. (As with Jeanne Dielman, I must confess, I was not at all convinced that Delphine Seyrig or Jan Decorte were the right choices…)

So, Sylvie Testud was quickly cast as Albertine. I was a little surprised: Testud was a young actress, with not that much experience. And she looked quite – how to say – everyday French realistic… Actually, Chantal wanted an Albertine who was not that glamourous. It took her more time to find an actor for Marcel. And I was surprised by her choice of Stanislas Merhar. Far away from how the Marcel should like to be, even in a contemporary setting.

Even if the acting of both actors may look a little – how to say? – against the grain, I am totally convinced that it was the right choice. Especially for one reason: both actors, there coupling also, gave the movie an authentic contemporary look. With another cast, let’s say a more glamorous kind of actors, I am sure as a spectator you would have remembered and been annoyed by the anachronistic situation: Proust today??? With more glamourous stars you would have been reminded that this was a relationship out of La recherche and the Belle Époque. Here you forget that La captive has something to do with Proust. Let’s say that her casting here was more in the Bresson tradition.

*

Beside the making of films, Chantal had two other obsessions, or should I say ambitions?

From her first film, Saute ma ville, on, one can notice that she wants to be an actress. And indeed, in several of her films she is acting. If not, she speaks texts off screen, like in News from Home. She liked reading text aloud.

It is her special feeling for acting that mark her sometimes wonderful choices for the casting (Delphine Seyrig in Jeanne Dielman of course). Sometimes however her casting and actor directing is less inspired.

It is after all strange that no other filmmaker asked Chantal as actress. She would for sure have accepted with joy.

Especially as a comical actress, or better: as a kind of slapstick actress she could have been interesting. You notice it in her films… but under her own direction, she was too sloppy, not precise enough in her chaotic ways. Indeed: every comical actor (from Chaplin over Keaton to Jerry Lewis) is extremely precise in his acting.

A good director could have brought this rare talent out.

I said already that she was an assiduous reader of novels. But above all she liked writing. Of course, she wrote two beautiful books.

And I am sure she would have liked to write more. The main problem for her was however that to be a writer you need discipline. You are on your own. (Or in the case of writing of a script for a feature film, she needed a coach, a co-writer who did not write, but one who organized her writing schedule.)

The making of a film is team-work. And you are in a sort of “system” … there is, from the beginning till the end a kind of pressure, a specific dynamism, a drive sustained by the different members of your team. You cannot give up in the middle of the process. You cannot afford to be lazy! There is always a deadline.

Writing, on the contrary, expects the writer to have the drive by him- or herself. I have the feeling that her not so good relation with Marguerite Duras, was actually based on some feeling of envy. Yes, she was a little jealous of the writer and filmmaker Duras!

*

As a director – and no longer co-writer – I was involved in two projects around Akerman. First, I directed Chantal and also Aurore Clément in a live reading of her book Une famille à Bruxelles. We did it in Brussels, and then in Avignon and for the radio, France Culture. It was Frie Leysen, a great fan of Akerman, who asked me to try to convince her to do something for Kunstenfestivaldesarts. Before that Chantal had had several offers for doing quite exciting things for the stage. However, she was always reluctant and asked me to be her co-director.

Then I adapted La captive for the stage. A one-act play for two actors. I was convinced that it was a strong “theatre text” — and I must confess that as a director I was more interested in stressing or bringing up the lighter side, the more humorous side of Proust. The script made other approaches possible I think, than the one which gave us La captive, the movie by Akerman. It would have been a Proust/Akerman light! It was called: Les intermittences du cœur…

After the Screening

In the novel, the relationship between Marcel and Albertine ends in a very vague way. Unsatisfying from a dramaturgic point of view… a feature film has to end! Especially with our initial choice: focusing on this relationship, Marcel/Abertine, and with this choice, consciously “erasing” all the other layers Proust masterly plays on in his novel. Akerman’s Proust is indeed an extreme choice. Differing much from all the previous adaptations of the novel (Schlöndorff, Ruiz, and also the never realized Pinter/Losey , and also Visconti project).

In the novel Albertine disappears; then 100 or so pages later in another context she is declared dead; then again, a few hundred pages later, she is not dead at all, but… another Albertine character appears…

As so often in À la recherche, characters jump from one book to another, and sometimes are quite drastically changed. Well, people do change over the years! But this is not the dramaturgy Chantal wanted!

So, in Akerman’s filmic approach this relationship has to end… The death of the character of Albertine – already suggested by Proust himself – was to be the end of our La captive. But a jump in time, as in À la recherche, would not have to been satisfactory. Jumps in time, forward or backward, are for Akerman “un-cinematographic”. The rather strange idea of Proust himself of a “false death” was also erased.

The inevitable suggestion of suicide could not be avoided. But how to keep such a “strong” event in the right register, of the atmosphere of all what preceded in our film? It should not work as an “accident,” a kind of deus ex machina. And in this case, Vertigo was no help.

*

One thing stood clear: for the end of the relationship – we had to go out of the prison, the captivity of Paris, to try to escape... and then finding an END. So, it was more or less a kind of “road movie” atmosphere, who was developed, … going somewhere, going nowhere…

And finally, the end could only be: murder or suicide or accident. No “fake” death as suggested by Proust!

*

In my memory the actual ending of the film – as one can see it now on the screen – was never written down as such in the script. It was more or less, after the written dialogue scenes in the hotel, a kind of: … !

So, no words here. For me the ending as filmed by Akerman is quite impressive, precisely because it is a mixture of three possibilities: the death of Ariane (Albertine) can be seen as an accident, a suicide, or even a murder.

Let me try to explain how I remember working on it.

First of all, we both admired very much the suicide by swimming of James Mason in Cukor’s A Star is Born (1955). Through the choice of the location – a modern villa on the beach near the sea, where the sea is viewed or reflected regularly by the big windows. The image of the sea is always present, seen from inside but also outside.

The strong presence of the sound of the waves, is then mixed with Judy Garland singing, a capella, the song ‘It’s a New World’ from Harold Arlen and Ira Gershwin).

The location seemed to us very dramatic – dramatic in the right way, meaning spatially suggesting a symbiosis and at the same time a dissolving of the couple.

The music of course playing here a very subtle roll of continuity.

*

I just had spent a week in this fabulous hotel in Biarritz, the Hôtel du Palais (build by the Princess Eugenia) where the rooms are literally in this wild sea… So instead of a villa, it would be a room in the Hôtel du Palais.

And again, some Hitchcock images were haunting us. The crossing of the lake by Tippi Hedren in The Birds, for example.

A crossing which reminded me of Zweimal gelebt, a short silent film from 1912 by the German director Max Mack. As in more silent films of this period, the theme of a “resurrection,” “reincarnation” or “duplication” of a woman, can be found. Inspired directly or indirectly by the novel of Georges Rodenbach Bruges-la-Morte (1892). In early cinema this theme is very present, in some way or another. And Vertigo is a late variation on it. Although the woman in the German movie lost her memory, and without knowing she is a bigamist… In the Max Mack film, near the end you see a long shot of the female protagonist crossing the lake in a boat, on her way to discover her first forgotten husband and her little daughter. A slow crossing as in The Birds!

I worked at the time at the Filmmuseum in Amsterdam, where not always being able to screen the film Zweimal gelebt with live piano music, I used to put on a recording of Rachmaninov, The Isle of the Dead, directed by Vladimir Ashkenazy. From the beginning till the end the score perfectly well fitted the film (as if written by… Herrmann!). The music which one can hear at the end of La captive is The Isle of the Dead. At several other moments (actually, four times) in La captive the Rachmaninov is also used.

(And I always had the feeling that Hitchcock must have seen this movie, when he was working in Germany… remembering it in The Birds, but also in Vertigo: the last shot of Zweimal gelebt, the woman jumping from a bridge in the river looks much like Kim Novak jumping from the Golden Gate Bridge…)

So there was a whole catalogue of images, referring to A Star is Born, Zweimal gelebt, and The Birds, we consciously or not consciously played with.

Images can be like palimpsests: one layer covering another or several others. In a way my obsession with this image of crossing a lake, was already present in my own Pink Ulysses (1991) – not seen by Akerman! – in the sequence of the crossing of the Lethe.

Consciously or not, images refer often to other images. So – again in Pink Ulysses – there is a projection of a film, and the projected image connected by the shadow of the projectionist. As in the beginning of La captive. In my film this idea is directly borrowed from Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom. Who, who knows, Powell borrowed from…?

But, back to the ending of La captive. Akerman’s is at her greatest here in the finale of her film: the framing, the editing, and especially her choice to have the character of Simon coming back to the shore in a boat, in this marvellous take of more than 2 minutes, rightly much admired by Raymond Bellour! In a short (four paragraphs) review of the film (Trafic 36 [2000]) he writes: “Comment évaluer la charge inouïe de ce plan, cette physicalité émotive avec laquelle ne peut rivaliser aucune autre sorte d’image, ni photo, ni tableau? (…) au long de ce film un équilibre rare a été trouvé entre les sentiments clairs et obscurs, et la façon dont les plans les contiennent, que ce dernier plan frappe au cœur, comme synthèse et supplément de ce que tous les autres communiquent.” Nearly half of the review is dedicated to an analysis of this last shot, indeed the core of the whole film.

*

One can be surprised or intrigued that here, for the ending – but also for the whole work on the script – our references were always visual or more precisely, cinematographic notwithstanding the fact I already insisted on, that Chantal was quite, in her way, a literary person, when working on the script our inspiration or references, came always in a kind of kaleidoscopic way from movies… never from novels!

Chantal radically did not want to dwell on the literary aspects of Proust’s À la recherche. On the contrary it was the filmic aspects, the filmic dimensions of his work that captivated (!) her. Filmic aspects of Proust who, of course, have often been underlined by many specialists, were not refused.

*

Quite intriguing however, as far as I can judge, Proust as writer never mentions “le cinématographe.” Notwithstanding the fact that the period À la recherche is covering, the early years of the twentieth century, was also the period where the cinematograph became a crucial new medium of entertainment. Especially in France with the productions of Pathé and Gaumont. Was this new medium too “modern” or too “technical” for an aesthete like Proust? What about his interest then – even passion – for the automobile, the telephone and even aeroplanes… so why is the cinema absent?

It is true that À la recherche starts around memories of the “camera obscura,” the magic lantern. So, the projection of images is not absent. Could one see this as a deliberate choice?

We have forgotten that the “magic lantern” was incredibly popular before the appearance of “moving images.” As home device or even toy, but on large scale also as spectacle. And this continued even during the first decade of the cinematograph. Especially, of course, in the less urban regions.

In a way one can see the magic lantern as a rival medium of the cinematograph. It can be compared with the later opposition, indeed battle, between silent movies and sound movies.

*

It’s recognized by the many admirers of the film that the music plays an important part in La captive, adding to the strength of the images.

In a text about the use of music in La captive, Philippe Fauvel in Cahiers du Cinéma (February 2021) notices that the music here seems to play the role of the off-screen narrator, present in the novel, but also in the other two À la recherche filmic versions. But starting on the script writing, the idea of using an off-screen narrator never entered our mind. “I am the narrator,” Akerman said. (Of course, like all auteur filmmakers!) Even if Akerman made beautiful use in the past – especially in her News from Home – of an off-screen voice. But it was always her own voice, and for that, never a male voice. Where here – if considered – it would have been mandatory to have a male narrator voice…!

But there is more music in La captive than the Rachmaninov.

Beside the “Così fan tutte” duet – in my opinion over-used – Ariane sings four times the beginning of a French song: “Tout ça parc’qu’ au bois de Chaville” (Pierre Destailles and Claude Rolland, 1953). I must admit that I, as would have been Ariane, listening to the whole lyrics, was surprised to discover that this was actually an extremely pacifist song.

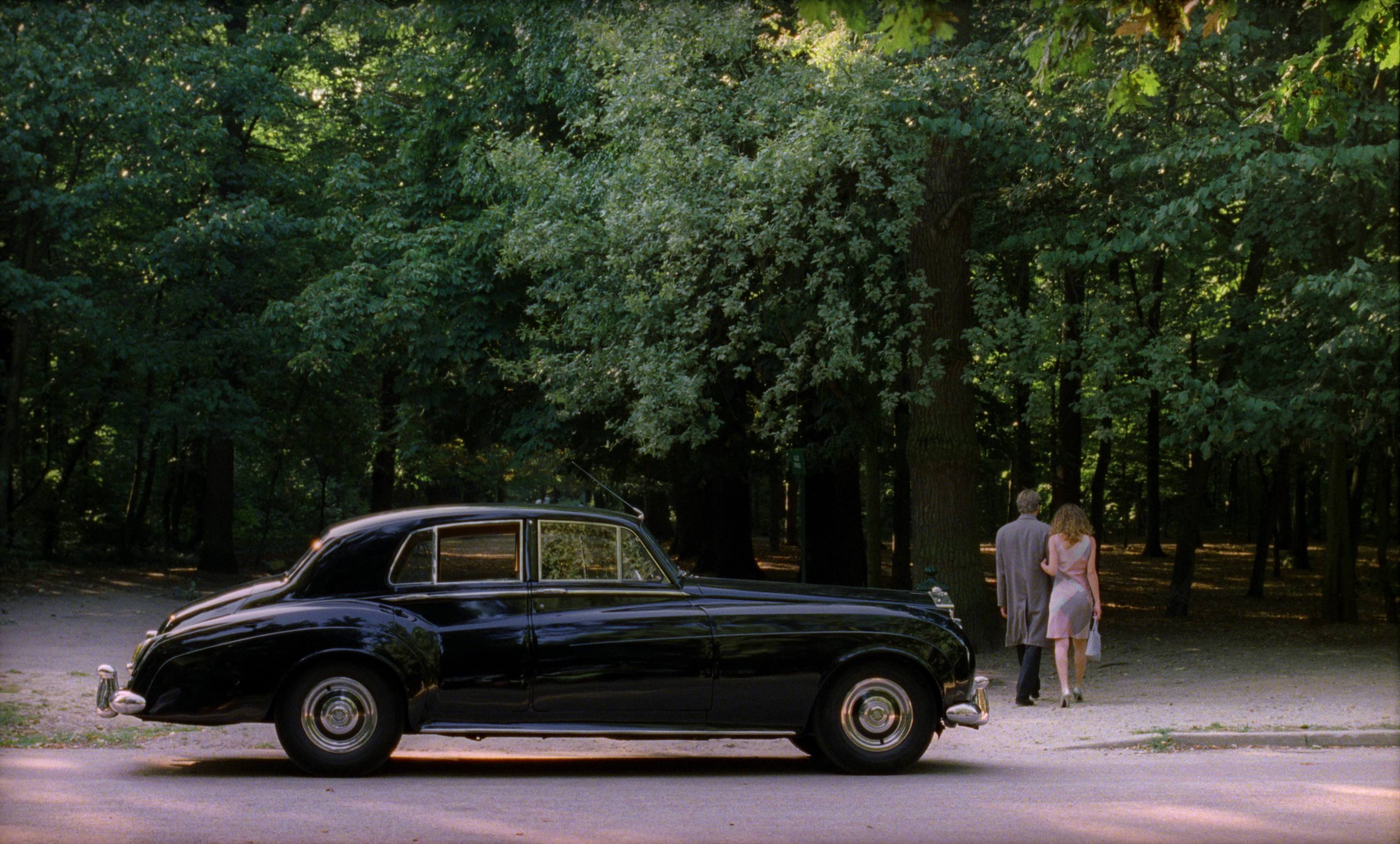

My suggestion for using the song however came to my mind for another reason than its pacifist theme (of course): It suggested the wonderful scene in the novel – but equally beautiful in Chantal’s version – of the walking of Ariane with Simon in the Bois de Boulogne. This could have happened also in the Bois de Boulogne/Bois de Chaville.

*

Remembering and writing here my co-working (not co-writing!) on the script, I may falsely give the impression that I am over-evaluating my participation in La captive.

I am not, I think, for the simple reason that the making of a film is always a collective enterprise and that I was only – in a specific way – part of that collective. I was bringing up material: some accepted, some rejected.

For a filmmaker who sets him- or herself or work consciously in the “auteur” category, this collective part of filmmaking is not really recognized.

Permit me to tell an anecdote about this attitude. When Manoel de Oliveira saw my first film, Casta Diva, which he appreciated much, he gave me some advice. “Never tell the audience your source of inspiration!” The film ends indeed with final credits where I thank several filmmakers, from Warhol to Visconti and Kümel who inspired me in one way or the other. Real authors like de Oliveira or Akerman never do this!

The French critics and filmmakers in the period of the Nouvelle Vague, stressing again the wish to consider the cinema as an art form, introduced the idea of the film director as an “auteur” – in French known as “politique des auteurs,” wrongly translated in English by “Author’s Theory” (wrongly because in the French use it is clearly suggested that this label has a polemist intention and is not at all a “theory”!).

(Earlier I wrote “again” because in the twenties there was already a strong movement trying to accept cinema as an art form, “le septième art.”)

The reference to literature is important, because in the French culture literature played a central part in the arts. A literary author is an individual. But even an auteur filmmaker has to work with a team.

The different members of the team have influence on what the filmmaker is doing. Of course, the choice of a team is, in the best “auteur” cinema, made by the filmmaker. For example, it was Chantal’s choice to ask me to work with her on the script!

But, and this is important, the final decision is made by her. The final images of La captive are her decision. And I am quite proud that she also made the decision to use there my suggestion to have Rachmaninov on the soundtrack! And in the best version, the one played by Ashkenazy!

Images from La captive (Chantal Akerman, 2000) | Courtesy of the Chantal Akerman Foundation

With the courtesy of Vinzenz Hedinger