Bio-Filmography of Chantal Akerman

From 1996 to 2015

1996

Un divan à New York (feature film)

“New York has changed hugely. Everyone knows it, says it and it’s true. When I was there in ‘71, the city was pretty run-down. That was its charm. It was that seediness I loved so much – and those contours. The city was bankrupt. Dangerous. Everyone said as much, but I wasn’t afraid. On the contrary, I was exhilarated. [...] I understand people who say that this film will be their last. Then, a few years later, they make another. People tell them, but you said... Yes, I said that. As for me, I never said anything. But I’d thought about it hard after Divan, it had been too difficult... That wasn’t why I’d wanted to make films, having been inspired by Pierrot le fou. With that film of mine, I’d truly become an adult. Joined the world of adults who act like adults. I’d left behind the minority that Deleuze speaks of and I’d fallen into the noise. Yes, with Divan, I’d stopped dwelling on the nothing that my mother talks of when she says, there’s nothing to add.” (Chantal Akerman: autoportrait en cinéaste, Paris: Éditions du Centre Georges Pompidou/Éditions Cahiers du cinéma, 2004)

The screenplay of the film was published simultaneously by Éditions de l’Arche. The critical reception was mixed and the film was a commercial flop.

“Divan was so heavy… At the beginning, when I’d wanted to make films, it was to express myself, I didn’t want to wage war. Writing lets you stay closer to yourself.”

Akerman created the production company Chemah I.S., which produced, notably, Sud, De l’autre côté, Là-bas, À l’Est avec Sonia Wieder-Atherton and No Home Movie.

Chantal Akerman par Chantal Akerman (documentary)

Self-portrait co-written with Janine Bazin and André S. Labarthe and commissioned for the programme Cinéma, de notre temps. It was, according to Claire Atherton, “a reconciliation with her cinema”.

“In the synopsis of the film Chantal Akerman par Chantal Akerman, I wrote that ‘if someone else was directing this film, they could “make like” more easily. As though the filmmaker’s words contained the truth of their work, as though they penetrated the origins of their desire to make, and continue to make. As though the filmmaker themself, their face, their smile, their silence and their body might speak the loudest about their work and as though there was always the temptation to seek out the author’s words, to try and find out more through them and finally for the author to be unmasked, if mask there were.’ I wrote that ‘making something about oneself, about one’s own work, poses multiple questions, disconcerting questions. (…) The question of the I and of the documentary, of fiction, of time and truth and thus too many questions so that naturally I would never be able to respond to them in that film.’ Nor in this book.

And why not? Because. Because I myself don’t understand, not everything. And because doubtless if I understood everything, I’d never make anything again.” (Chantal Akerman: autoportrait en cinéaste, Paris: Éditions du Centre Georges Pompidou/Éditions Cahiers du cinéma, 2004)

1997

Le jour où (short film)

“The day I decided to think about the future of cinema, I told myself I wouldn’t live to see it. I asked myself if the future is always in front of us. So I looked ahead, then I turned around. I wondered if the people who walk with their heads down have a sense of the future, or only those who walk proudly, heads high. I said to myself that, for me, the future was behind me, because one doesn’t say about someone my age that she has a bright future ahead of her. So the day I decided to think about the future of cinema, I got up on the wrong side of the bed. When you get up on the wrong side of the bed, you can’t think, and, even less, think about the future of cinema.” (Voice-over by Chantal Akerman in the short film Le jour où, part of a collective film about the future of cinema, produced to mark the 50th anniversary of the Locarno Film Festival in 1997) In an interview with Nicole Brenez in 2011, Akerman described the film as follows: “Essentially, a tribute to Godard.”1

Akerman started to teach at Harvard’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts.

1998

Une famille à Bruxelles (book)

First publication by Éditions de l’Arche; a fictional text, in flux, encompassing multiple subjectivities and full of autobiographical references.

“Everyone lives their own life. Especially when you’re far away. And even when you’re close, but when you’re close you can feel it over the phone and you can say see you soon and sometimes you’ll see each other soon. You also say see you soon to those who are far away on the phone but you know that you will not see each other soon and sometimes you don’t call those who are far away or almost never even when they’re close relatives.” (Chantal Akerman)

Self Portrait / Autobiography: A Work in Progress (installation)

Presentation of the installation at the Carpenter Center, Harvard, then at Sean Kelly Gallery in New York and Frith Street Gallery, London.

First photography on Sud with Raymond Fromont (sound engineer and asssistant cinematographer), shot on Sony MiniDV, in Louisiana, Georgia and Texas. An initial cut was presented in Paris that autumn.

Start of work on the script of La captive with Eric de Kuyper.

“We decided that at the root of the film there’d be Proust. Then we hastened to say let’s forget about Proust. And think about the film.” (Eric de Kuyper, Trafic 35, autumn 2000)

“I think that cinema often suffers from too much scripting, or from the wrong kinds of script. That’s why I often try to write screenplays that are also pieces of writing that already give me pleasure. Eric de Kuyper told me, something I’m not aware of at all: ‘what’s crazy is that you made the film against the script. I don’t understand why.’” (Chantal Akerman, radio broadcast, 27 September 2000)

1999

Sud (documentary)

Presented at the Cannes Film Festival during the Quinzaine des réalisateurs (Directors’ Fortnight); it was the first ever documentary screened at the Quinzaine.

“Sud was shot in the American South, and its strength is the dialectic between past and present. Chantal went down there, attracted by Faulkner and Baldwin. The film begins gently, almost peacefully: people talk about how everything seems better now than it used to be. But little by little, in this quiet landscape, you start to feel anxiety. The strident sound of insects becomes threatening, and so do the trees. We begin to hear about slavery and lynching, and then, as the tension grows powerful, we start to question the placidity we saw at the beginning.

Chantal and I often listened to Billie Holiday’s Strange Fruit during the editing process. We even considered putting the song in the film. Ultimately, we didn’t even try. But we put in trees – one, two, three of them. When you look at them in the film, you can’t help thinking about hangings. And the shot of prisoners working in a cotton field conjures up the memory of slavery. What guided me during the construction of Sud was Chantal’s extreme attention to the present. We never show or describe the past, but it is dredged up by the present.” (Claire Atherton, “L’art du montage”, translated by Nicholas Elliott, Sabzian, 12 December 2020)

Une famille à Bruxelles (lecture)

Story read by Chantal Akerman and Aurore Clément, directed by Eric de Kuyper. First presented in Avignon.

2000

La captive (feature film)

Presented at the Cannes Film Festival during the Directors’ Fortnight.

Chantal Akerman: “I know that the question of modernity versus non-modernity is a real one. But it’s not something I think about when I’m making a film. In the seventies when I started making films, some of which were dubbed experimental, I had this notion of the avant-garde in the back of my head and the idea of always moving forward. It’s something I don’t think about at all anymore. [...] [The character of Simon] is both obsessive and romantic. He has this idea that when you love someone, the two of you have to become one. And she says to him: ‘We’ll never be as one. We will always be two.’ I don’t know where this notion comes from. I think that even today every kid of fifteen, sixteen or seventeen thinks that when they meet the love of their life they will be as one. Later on, even if you dream of that, you know perfectly well that it’s false. [...] When I finished writing the screenplay, I told myself that I didn’t understand what I’d written. And I told myself that I’d understand the scenario better when the film was finished. Only when it was finished, I still couldn’t figure it out. And I said to myself, that’s the strength of the film, this opacity which raises questions for all who see it, introducing a feeling of confusion and resistance.”

Reading of Une famille à Bruxelles at the Kunstenfestivaldesarts, directed by Eric de Kuyper.

2001

Woman Sitting After Killing (installation), conceived and edited with Claire Atherton

Installation based on the last shot of Jeanne Dielman, shown at the Venice Biennale.

Chantal Akerman teaches at the European Graduate School in Saas-Fee, Switzerland.

Filming of De l’autre côté in Mexico and the United States, accompanied by artist and filmmaker Robert Fenz, among others.

Akerman works on several projects that are never made: adaptations of Colette’s Chéri and La fin de Chéri, with Eric de Kuyper; and of The Price of Salt, by Patricia Highsmith.

2002

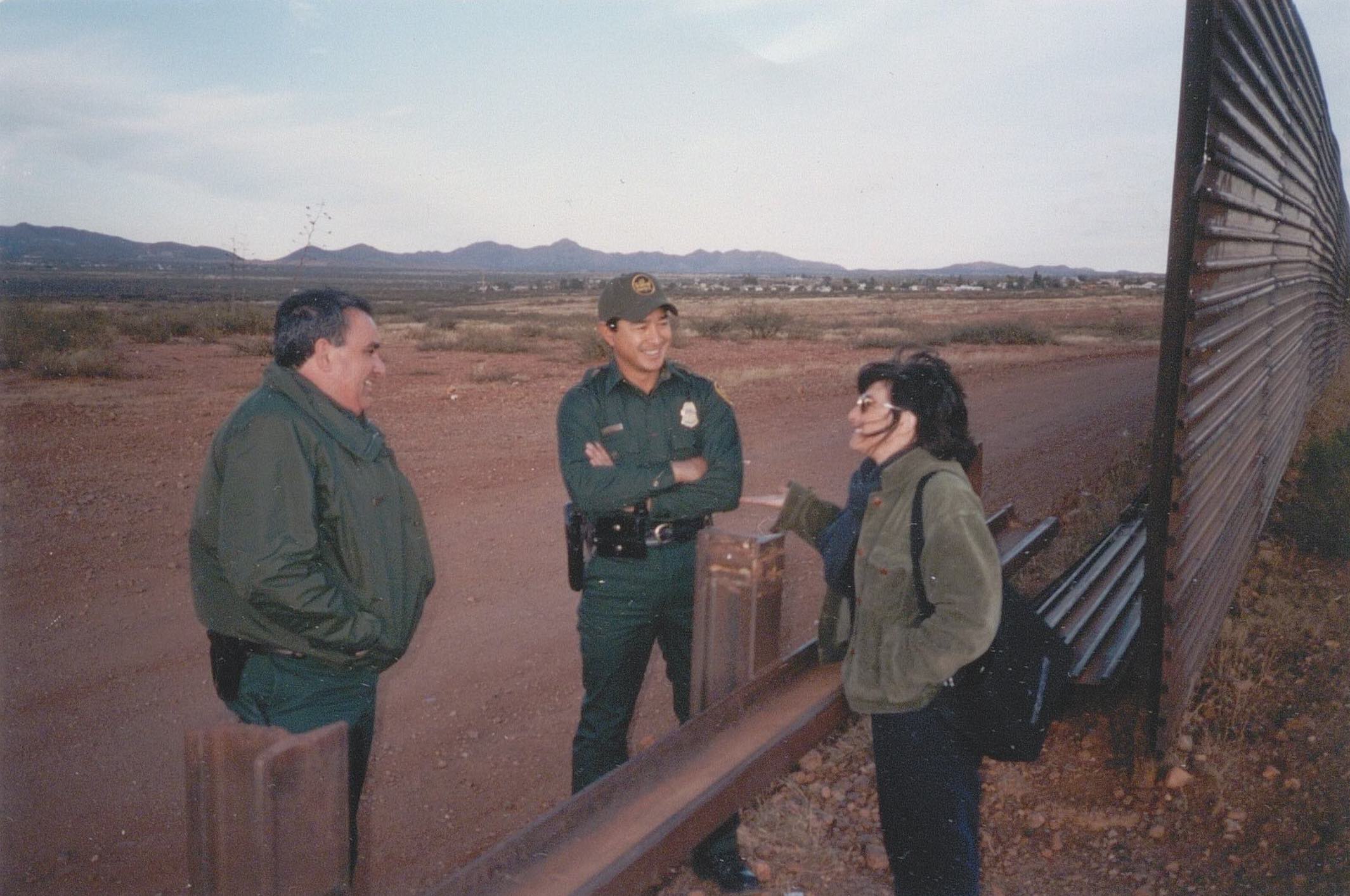

De l’autre côté (documentary)

Presented out of competition at Cannes.

Akerman writes a letter to her producer Thierry Garrel after he rejects her proposed project Du moyen-orient. In the pre-production stage, she writes him a letter defending her new film De l'autre côté. She says: “[that] could almost be used for all my documentaries. To forever defend the documentary cause. Forever is a big word, but suddenly I like it.”

“You’ve asked me to clarify my thoughts. You would like to know how I’m going to tackle this subject. [If I did that] I too would feel better, calmer, but also likely less interested in the project, because what fascinates and frightens me at the same time when I set out to make a documentary is to discover that documentary in the process of making it. To clarify my thoughts would, I believe, go against the very grain of the documentary project, and it therefore scares me somewhat. Because, in making it, I allow myself to be led, I’d almost say led blindly, and I become a sort of ‘sensitive sponge-plate’ with a free-floating attention, from which the film eventually emerges or floats to the surface.” (Chantal Akerman: autoportrait en cinéaste, Paris: Éditions du Centre Georges Pompidou/Éditions Cahiers du Cinéma, 2004)

“The most effective politics is not one of portable cameras trying to stick close to the bodies of clandestines running in the night, towards the small vans where they will be piled up. It’s the one setting up flush to the wall, on the day when the cars pass by indifferently, the evening when children play baseball, the night when the spotlights compose a fantastic ballet; the one confronting its silence with the words of those who, on one side, describe their stubborn journey in search for a ‘form of better life’, on the other side, confer their problems of density and environment. De l’autre Coté constructs the space of a modification of relations between those who speak and those who keep quiet. This modification could define the programme of a minority art. It is also a fairly good definition of politics.” (Jacques Rancière, “Un cinéma des minorités?,” Cahiers du Cinéma 605, October 2005)2

From the Other Side (installation)

Presented at Documenta 11 in Kassel.

“I also want to tell you about the installation From the Other Side because it as born from a very specific desire. Chantal wanted to put a screen in the desert, on the border between Mexico and the United States, to project part of her film On the Other Side, which was filmed in this border zone, and to film the projection of this extract in its authentic setting: the desert. She wanted this image to be broadcast live at Documenta 11 (2002) in Kassel, where the installation was to be shown. This vision was the starting point of our work. Very quickly, we thought that the image of the big screen recaptured on film could be the culmination of the viewer’s journey. It would therefore be screened in the final room. And we imagined that the extract from the film projected in the desert would be simultaneously broadcast on a plasma screen at the start of the installation, in the first room. The third room would therefore echo the first. [...] The big screen was mounted in the open air, between two mountains, one Mexican and the other American. In the morning, in Kassel, we could barely see the two mountains in the image being broadcast because it was night in Mexico, but we could see the image of the film projected on the big screen very clearly. Then as it got later in Kassel, day broke in Mexico, the mountains appeared and the image on the screen faded. We could still hear Chantal’s voice mingling with the wind. Subsequently we mounted a reduced version of this desert projection, which gradually passes from night to day.” (Claire Atherton, “L’espace des installations,” interview with François Bovier and Serge Margel, Décadrages, 2022)

2003

Start of the collaboration with Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

From the Other Side: Fragment (installation)

Presented at Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, Rotterdam.

Avec Sonia Wieder-Atherton (video/installation)

“Encore Sonia”. Screened at Noisiel, as part of the festival Temps d’images.

“It is said of Sonia Wieder-Atherton that she was born in San Francisco, that she grew up in New York and Paris, and it’s true. That if she chose the cello, it was because she wanted to play a stringed instrument whose sound she could extend for as long as she liked. It's true. [...] And that she grabs us, takes us with her, so far and so fiercely into territories that are still unknown, sometimes dark, sometimes light, old or new, in a mixture of pleasure and tension. It is also said that hers is an atypical career path, and an atypical repertoire, that’s what people say. But as for her, she searches, she searches again and again, she advances, she moves, she never stops searching, she searches for the breach. The sound, the breath. The breath of origins. It’s true.” (Chantal Akerman, Avec Sonia Wieder-Atherton, press release for the film, 2003)

Une voix dans le désert (installation)

Presentation at Marian Goodman Gallery in Paris.

“There is really nothing to say about her. Every day, she left and came back around the same time. She hardly went out again. Except on Sundays, she must have gone to the beach, I think. Because on Sundays there was always a little sand on the stairs. Sometimes she went out to smoke. I don’t like when people smoke inside. She’d wander down the block, smoking, thinking. About what? That I can’t tell you. […] I wonder whether she is in Mexico or someplace else. Sometimes I tell myself she is dead. But that’s just the dark ideas I have. She’s not dead. She is in Mexico or elsewhere but I can’t say where. I never saw her again. Well, once I thought I did… But I’m not sure it was her… It wasn’t far from here… on the corner of the street, and the boulevard. There are a lot of Mexicans there. I was in the car, and when I got there, no one was there. It must have been a hallucination.” (Voice-over in De l’autre côté)

2004

Marcher à côté de ses lacets dans un frigidaire vide (installation)

Demain on déménage (feature film)

Co-written with Eric de Kuyper; screened at Berlin Film Festival.

“Sylvie Testud, the main character in the film, calls me a sad clown. I’d never thought of that before, but maybe it’s not wrong. That’s the other side, or the end. With Demain on déménage, I nonetheless tried to rewind to the beginning, the burlesque of the beginning, but obviously I didn’t quite get there. It’s natural. One can’t start over again. However, there is something burlesque to the film though the joyous desperation is perhaps less visible now than then. In Demain on déménage, Charlotte doesn’t cry out. Not a bit. She lets things happen without defending herself. Sylvie, doubtless unconsciously, is secretly like me.” (Chantal Akerman, Chantal Akerman: autoportrait en cinéaste)

Autour de Jeanne Dielman (Sami Frey, 1975) (feature film)

Shot in January 1975 during the making of Jeanne Dielman, black and white video, edited by Chantal Akerman and Agnès Ravez.

Le frigidaire est vide. On peut le remplir (text)

Long autobiographical text in Autoportrait en cinéaste.

Akerman is made Commander in the Order of Leopold, Belgium’s most prestigious honour.

2005

Autour d’hier, aujourd’hui et demain (feature film)

The making-of Demain on déménage, conceived by Akerman and edited by Claire Atherton from images shot by Renaud Gonzalez during filming.

D’Est en musique (film with live musical accompaniment)

With Sonia Wieder-Atherton on the cello and Laurent Cabasso on piano.

2006

Là-bas (documentary)

Filmed alongside Robert Fenz; screened at the Berlin Film Festival.

“In fact, I neither wanted nor had the willpower to make a film about or set in Israel. [...] I immediately had the impression that it would be a bad idea, even an impossible one – almost paralysing, almost sickening. [...] The decisive thing was that one day there was a frame and therefore there was a shot. One day, I took up my camera and stationed myself somewhere and suddenly there was a frame, a shot. And I said to myself, this frame is great. All you have to do is wait for things to happen. [...] So I looked out the window, a window covered with blinds made of a very fine straw, with very fine slats, and very fine gaps, and I could see through, I could see but I could not be seen, at least I don’t think. And it was like a scene.” (Chantal Akerman, interview with Franck Nouchi)

Production of a DVD box set of Akerman’s early films by Carlotta Films. Akerman and Atherton film interviews with Babette Mangolte, Aurore Clément and Akerman’s mother Natalia for the DVD extras.

2007

Tombée de nuit sur Shanghaï (short film)

Short film as part of the anthology film O Estado do Mundo [The State of the World], which also included contributions by Ayisha Abraham (One Way), Wang Bing (Brutality Factory), Pedro Costa (Tarrafal), Vincente Ferraz (Germano) and Apichatpong Weerasethakul (Luminous People); screened at the Cannes Film Festival.

Je tu il elle (installation)

La chambre (installation)

In the Mirror (installation)

Three installations created for the exhibition Ellipsis at the Museo Tamayo in Mexico.

2008

Femmes d’Anvers en novembre (installation)

The exhibition Chantal Akerman: Moving Through Time travels across the United States all year, stopping in Houston, Cambridge, Miami and Saint-Louis.

2009

À l’Est avec Sonia Wieder-Atherton (installation/video)

Maniac Summer (installation)

Tombée de nuit sur Shanghaï (installation)

Chantal Akerman, de ça (medium-length film)

Video interview directed by Gustavo Beck and Leonardo Ferreira.

Big retrospective in Brazil.

2010

Shooting of La folie d’Almayer in Phnom Penh and Koh Kong, Cambodia.

2011

Akerman begins to teach at at City College, New York; she will work there until 2014.

La folie Almayer (feature film)

Presented out of competition at the 68th Venice Film Festival.

“A tragic history, like ancient tragedies that never grow old. A story as old as the world. A story as young as the world, of love and madness, of impossible dreams.” (Film synopsis written by Akerman)

“La folie Almayer ‘works’ on you a great deal after the screening. In the moment it leaves things unsaid, but the images come back to haunt you, I think. It’s all because I’m not trying to say something I already know. I work from my subconscious, and it speaks to another subconscious – that of the viewer. La captive was the same. When I finished the script, I didn’t know what the film was about. What is this thing? I asked myself. Little matter, I’ll know when the film is done. I’ll understand. But it took a while.”

“It’s scarcely an adaptation. Conrad’s novels are above all novels about men who have committed errors are more or less in the process of redemption. It’s a Christian and masculine notion having to do with law and, by contrast, I made a film that was neither Christian nor about the law. It’s a film where I tried to surpass mastery.” (Interview with Philippe Piazzo, UniversCiné)

Viennale retrospective accompanied by a catalogue including Nicole Brenez’s now famous ‘The Pyjama Interview’.

2012

Maniac Shadows (installation)

My Mother Laughs Prelude (installation)

Too Far, Too Close (exhibition)

Exhibition at M HKA Museum of Contemporary Art, Antwerp.

Big retrospective organised by the festival Doclisboa, accompanied by an exhibition entitled Passagens, also including two installations by Pedro Costa.

2013

Ma mère rit (book)

Published by Mercure de France.

“I wrote it all down and now I don’t like what I’ve written. That was before, before the broken shoulder, before the heart operation, before the pulmonary embolism, before my sister and my brother-in-law called me so I could say goodbye to her (for ever). Before she returned home to Brussels for the last time. Before she laughed. Before I realised that maybe I’d got it all the wrong way round. Before I realised that my vision had been narrow and delusional. And that this was all I could manage. Not even faithful to my own truth. For now, my mother is alive and well. That’s what everyone says and everyone also says that she’s strong and nobody understands how she’s managed to survive. She hurts all over but her hair has grown back. It’s a miracle.” (Opening of the book, published as My Mother Laughs, translated by Danielle Shreir, London: Silver Press, 2019)

In 2013, the mother of filmmaker Chantal Akerman falls ill. Akerman flies from New York to Brussels to look after her, and during this period she writes – writes about her childhood, about her mother’s escape from Auschwitz, which has gone unmentioned, about the difficulty of loving her partner C., about her fears over what she will do when her mother dies. Between these revealing fragments of her life, she sets images taken from her films.

In-depth retrospective at the ICA in London organised by the collective A Nos Amours (Adam Roberts and Joanna Hogg).

2014

On 4 April her mother Natalia Akerman passes away.

De la mèr(e) au désert (installation)

2015

No Home Movie (feature film)

Screened at Locarno International Film Festival.

“I had the feeling for a long time – my mother went into the camps and never said a word about it – that I had to talk for her, which is crazy because you cannot talk for someone else. So I was obsessed by that, by her life, I was also obsessed by the way when she went out of the camps she made her house into a jail. That’s Jeanne Dielman. Now I can tell that, but I was not aware of that when I did it, you know? So I thought that I was the one that had to make, because she would not say anything, that I was the one who was going to bear witness instead of her.” (Chantal Akerman, interview by Daniel Kasman for MUBI, 17 August 2015)

NOW (installation)

Conceived and edited with Claire Atherton, shown at the Venice Biennale.

I Don’t Belong Anywhere: The Cinema of Chantal Akerman (Marianne Lambert, 2015)

Filmed for the series “Cinéastes d’aujourd’hui”: a portrait of Chantal Akerman through her works.

On 5 October, Chantal Akerman commits suicide. She is buried at Père-Lachaise in Paris.

After her death, numerous tributes pour in from filmmakers, critics and viewers across the world. Below, a small sample of them:

“Many of her films had an impact on me, as well as the incredible installations she created for museums, but above all it was my discovery of Jeanne Dielman that had an immeasurable influence on me when I was studying film. I’ve often watched it since, at home, and remain amazed at the boundaries she breaks in the film, what she invents in terms of the narrative and her relationship to the character. When I made films like Gerry, Elephant and Last Days, it was a more than critical influence on me: for me, no one existed but Bela Tarr and Chantal Akerman.” (Gus Van Sant, Libération, 6 October 2015)

“I met Chantal Akerman at Anthology Film Archives, which had only recently opened, in 1970. She must have been about 20, and spent several months in New York at the time. She’d already made a short film but Anthology was her university, her film school. […] I don’t know if I’d say we influenced her, but I think that the cinema she discovered then, mine and that of all the others, maybe helped her to develop an interest she already had for real life and her own life. A variation on the diary film approach, which reinforced her own ideas – it’s sometimes reassuring to realise that others are doing what you have in mind. [...] She had a combativeness, a very direct way of doing things, had no doubts, and perfectly controlled the ideas and material she planned on using, but always in a personal, a very personal, way. All her work became more and more personal over the years, culminating in the film about her mother. We don’t know what she would have done next, which is so sad. All her work is like a great film epic where one can link together all the constituent parts.” (Jonas Mekas, Libération, 6 October 2015)

“’I was born as an old baby, in 1950’, she said. Birth of a wünderkind, a wanderer, a wonderer and writer. She brought us her acute view, her unmistakable voice, and left us her art and much more as comfort.” (Vivian Ostrovsky, Senses of Cinema, December 2015)

“Faced with Chantal Akerman, I understood that you can be an adult and still want to learn, all the time, without stopping. She had a very youthful appearance, permanently wide-eyed. She pushed things to their limits and loved imperfection. She had been manic-depressive, and there were difficult moments as well as very sunny ones. When she was low, it was melancholy more than anything. She had the curiosity of a teenager, always ready to get excited about something and then be gripped by passing doubts. I don’t think that Chantal Akerman defined herself as complete, as a finished person. Adults take on roles: doctor, lawyer, director. She didn’t even want to fully endorse the latter. Chantal was so sunny, so present, that when she left a room, she created a void.” (Sylvie Testud, Libération, 6 October 2015)

“For her cinema was a way of living and thinking. There was a necessity and self-evidence to aesthetic work – whether you think of Jeanne Dielman or d’Est, where whole sequences linger in the memory. In all her work she achieved maximum effect with minimal means, a moral vision of form light years away from some current posturing. Her ending was her own but she has long been and will remain one of those authors that stick with you.” (Cathérine David, Libération, 6 October 2015)

“Each film, each installation was like the first time. We had no rules, no fear, no barriers. Each time we embarked on a new adventure, both sensory and intellectual. Our discussions were very straightforward. There were few words, as if too many words risked damaging something. We often said ‘it’s beautiful’ or ‘it’s strong’. There were words we liked, she said we have to be drastic, uncompromising. We also said that we were going to cut to the quick. Sometimes I told her: ‘we need to complexify it’. She liked that word. She said to me: ‘Yes, that’s it, complexify it a bit.’ That was when we felt that too much had been said, things were too linear. But once the editing was done, there was a great simplicity to the film’s construction. To complexify wasn’t to complicate, but to add weight and counterweight, to refine the tension.” (Claire Atherton, extract from a text read during an evening held in honour of Chantal Akerman at the Cinémathèque française on 16 November 2015)

“With heavy hearts we have tried to gather our thoughts. Our perspective is hard to describe; in curating Chantal’s work, we came to know her personally. And in doing so we discovered that Chantal’s films and Chantal herself are, in so many ways, the same thing. She eschewed categorisation – as an artist, as a female film-maker. She was simply Chantal Akerman.” (Joanna Hogg and Adam Roberts, The Guardian, 8 October 2015)

“[Discovering Jeanne Dielman] was one of those experiences that change the way you think, see and conceive of cinema. It had a profound influence on the way I understand narration or how a woman’s life can be depicted on film: the experimentalism of the film in honing in on the routine of a woman’s domestic tasks and this Ozu-style camera which unflinchingly confronts her in her kitchen, all this aroused in me an unimaginable emotion. [...] This film exercises a unique power on you, through its unique way of focusing on certain things and excluding others, its political character, its particular ethics. [...] She had a cinematic language of her own, comprised equally by formal invention and humour. I think about the last time I saw her in Paris, and it makes me very sad.” (Todd Haynes, Libération, 6 October 2015)

- 1All translations in this paragraph by Sis Matthé. Original article available here.

- 2Translation by Stoffel Debuysere, available here.

Image (1) and (3) from Collections CINEMATEK - © Fondation Chantal Akerman

Image (2) from Le jour où (Chantal Akerman, 1997)

Images (4) and (6) from I Don’t Belong Anywhere: The Cinema of Chantal Akerman (Marianne Lambert, 2015)

Image (5) from No Home Movie (Chantal Akerman, 2015)

Special thanks to the Chantal Akerman Foundation.

This second part of the bio-filmography of Chantal Akerman draws extensively on the chronology in Chantal Akerman. Œuvre écrite et parlée (Paris: Éditions L’Arachnéen, 2024).

Translated by Clodagh Kinsella except when otherwise stated.