Vertigo of Time

The method

Sergei Loznitsa is one of the most rigorous and formally disciplined filmmakers working today. Always taking a position of an observer, Loznitsa puts it to extremes, as if he is testing his own ability, as well as an ability of cinema per se, to stay still and not to collapse in the face of a social upheaval (The Event), a revolution (Maidan), an existential breakdown (Blockade, Austerlitz), or simply in the face of emptiness, void, nowhere (Portrait, Landscape, The Train Station, The Letter). This stoicism serves as a moral ground for his works and defines their style.

Loznitsa’s view is enduring and challenging at once. It is defined by distance and detachment, continuity and slowness, stillness and quietness, which sometimes result in silence or muteness. He is a minimalist, who is as precise as only a true mathematician can be. His documentaries are commonly associated with a non-narrative cinema, however they do have a touch of a narrative within them. A singular image itself is an element of narration, exposing an untold yet self-revealing story that lies behind it. Of course it is never verbalized, as Loznitsa always works in a “no comment” mode. In that sense it’s a pure photographic cinema. Portrait can be defined as a series of still photographs. Landscape is a series of continuous uninterrupted shots too, presented almost as a video installation. Based on newsreels and found footage, Blockade and Revue explore the very nature of a film image as a “documented truth” and expose the ways in which it does not replicate the actual reality, but always presents something which differs from it.

Proto-cinema

His black-and-white documentaries (Settlement, Portrait, The Letter) give the impression of being shot in the beginning of the 20th century by a contemporary filmmaker, who looks back in time to explore the very origins of cinema. He observes the reality as if the cinema has just emerged from photography and has not yet been “corrupted” by literature, theater, music and nor even by montage. As if cinema has not yet become cinema. That is another side of Loznitsa’s “archeology of vision”, which resonates with his purely archeological found-footage films (The Event, Revue, Blockade) and also with his fundamental preoccupation with the past.

Settlement, his documentary on the rural life of a remote Russian village, even looks like a film found in the early XX century, as its scratched 35mm black-and-white texture and faded, misty colors perfectly match with the archaic lifestyle of the peasants, which has not changed since XIX century. In the similar manner the characters of The Letter, patients of the forgotten and abandoned asylum deep in the Russian countryside, are filmed as shadows, whose bodies are hardly visible and are reduced to silhouettes as the only traces of their ghostly presence. Loznitsa provides a double distance, or double abstraction: not only he depicts the present as a never-ending, eternal past, but he also films it in the style of that ephemeral, mythical past, which can be attributed to the early cinema and even to the pictorialism which preceded the invention of a film medium. Not only the space is static there, the time is static too.

In Portrait Loznitsa goes even further in his experiments on time, space and continuum. The film is basically a series of long still shots of Russian villagers, but the stillness of images is reinforced there by the physical stillness of characters, who stand or sit in front of the camera without even a slightest movement. The combination of static bodies and static space provides a different sense of time, which is moving and static at once. Loznitsa removes the difference between movement and stillness, thus removing the difference between time and space and taking both of them out of an actual, “documented” continuum. Life presented in Portrait has its own category as well as dimension of time, which is neither the present, nor the past and most certainly not the future. In a similar way the time in Landscape is locked in a perpetual loop, or closed circle, formed by the series of panoramic shots which follow the line of people waiting for a bus, rendering both the waiting process and the line itself endless.

Throughout the history of the documentary cinema, it has always been the filmmaker’s subjective choice, which determined what is filmed and is visible and what is cut out and remains unseen, or invisible. In that sense, the outlook of Loznitsa presents the latest stage of the evolution of this genre, which ends up being as selective and meaningful as possible. The act of making such an artistic choice is an event itself, which means it is never random and is not even frequent. At the same time the choice of what is filmed and framed works as a key to the much larger world of the unseen as invisible that hides inside an image. Loznitsa chooses only those images that extend their own limits and serve as an evidence of a bigger picture, which lies beyond them.

This is what may be called an “economy of images”: in the digital age of overproduction, abundance and devaluation of images Loznitsa films economically, as if the resources of cinema and of a man’s vision are not just limited but are about to be depleted. This is Loznitsa’s panacea for the general “inflation of images” that happens today, and a clear example of his moral, ethical position.

Event as phenomenon

Loznitsa’s documentaries have very little to do with the traditions of cinéma vérité, such as spontaneity, improvisation, direct, active and even activist presence in reality, which is seen as a free flow, an uncontrollable energy, an unpredictable current. Unlike the filmmakers associated with cinéma vérité movement, Loznitsa has the intention to detach and completely deconstruct the actual reality by taking it out from its default context and putting it on a higher, more complex level of mimesis. Even Maidan, his most explicit political documentary shot during the eponymous Ukrainian unrest, transcends the level of political urgency, turning into an almost epic fresco, portraying the (re)birth and sacrifice of the nation, rendering current political events a status of mythological archetypal magnitude. Using the compositions of epic tableaux reminiscent of classical paintings, he does not focus on single characters but rather presents the entire group of protestors as one unified body, driven by the same will and by the shared sense of solidarity.

Loznitsa’s outlook is so distanced that it sets a totally different, if not a transcendent perspective on reality and strips it off cliches of conventional documentary realism. His documentaries always expand the limits of social and political commentary, regardless of its subject matter, and transform the real into the surreal, the current into the mythological, “the raw” into “the cooked”.

The sleeping, lethargic, deeply quiet characters of The Train Stop resemble the classic portraits of Russian painters of XIX century known as “the wanderers” (peredvizhniki), and at the same time remind us of Andy Warhol’s Sleep, the iconic work of film avant-garde. The train station itself is like a forgotten limbo there. It’s a room where you endlessly wait for something that would never come, and during that process even forget what exactly you are waiting for, if you have ever known that.

A similar Beckettian atmosphere is palpable in Landscape, an observational portrait of a crowd of people waiting for a bus at some remote station during winter. They are willing and hope to leave but remain unmoved, as if they are destined to remain in-between: neither here, nor there. Their close-ups are intertwined with the scraps of their monologues about their everyday lives. Put together, these voices sound like a disrupted chorus, where everyone speaks about his own, and yet he is indistinguishable from the others. In this “communal body” there is no difference and no distance between the self and the other. Such closeness is alienating and it only highlights the impossibility of communication.

In The Train Station and partly in Landscape the physical density of space and particularly of bodies exceeds the continuity of time, creating a visceral feeling of time devoured by space. Not being able to remember what they are waiting for, or rather not knowing what to expect, the characters in these films are losing the sense of time too. They are suspended in a limbo-like space, a space where there is no time at all. Hence they kind of fall out of any default context, including the context of present, and the context of history too. This is how Loznitsa decontextualizes and deconstructs the actual reality he is filming, presenting it not as an event, but rather as a phenomenon stripped off all markers or labels.

The future archived

Loznitsa films current events as if they already became a part of the long-distanced past, and the other way around. In his archival found footage works he excavates the past and its hidden elements like an archeologist, placing them into the context of the present and even of the future, and reveals the indistinct links between them. Perhaps he even separates, detaches an event from a moment when it happened and looks at it from a distanced point of view of a phenomenologist. In that sense Maidan and Austerlitz, which seem to record current events, are on a par with Blockade, The Event and Revue, his found-footage films, based on archival materials.

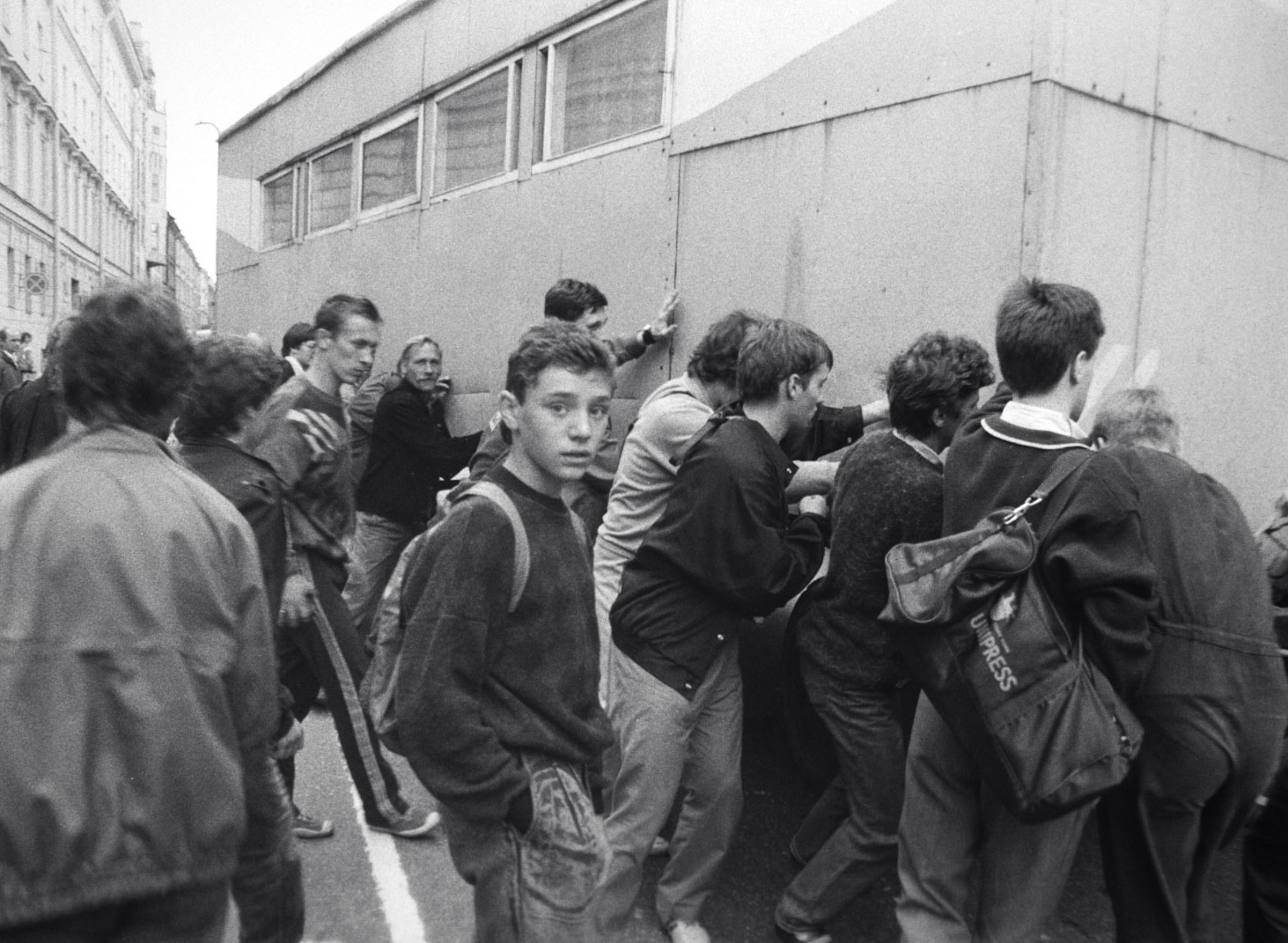

The Event may have been shot by Loznitsa himself, as the archival chronicle of Soviet anticommunist protest in August 1991 in Leningrad, followed by the collapse of USSR, perfectly resonates with the current political situation in Russia and at the same time resembles the black-and-white texture of Loznitsa’s own films. In a way Loznitsa uses found footage like a contemporary artist uses ready-mades, placing them in a different (contemporary) context and thus revealing some hidden meanings. The Event is a dramatic parallel to the antigovernment demonstrations that are happening in Russia today and in that sense it’s teetering between nostalgia and melancholia. Loznitsa definitely makes an unforgettable memorial to those demonstrators who remained anonymous, but this is an homage to a revolution that was not there. By revealing this “phantom” nature of this revolution, the film undermines the belief, shared by many liberals, that an event like this is possible in Russia today, or that it might become possible in the near future.

Loznitsa rediscovers the archival footage as a perfect evidence that reveals its true meaning and its true power only after a filmed event had happened and, most importantly, after it has been forgotten and erased from the collective and even from a personal memory. This is exactly what happened to the early Russian 90s which Loznitsa revisits and revives in The Event. He positions himself as an eyewitness to the events, even though it is known that at the time of the coup d’etat he was nowhere near Petersburg. Like an archeologist, he recalls and re-experiences the lost era in its authenticity and purity, making it free of its subsequent interpretations and questioning the legitimacy of such interpretations. At the same time the complex relations between the event itself and the institutionalized as well as alternative knowledge about it, becomes the core of the film.

![(4) Predstavlenie [Revue] (Sergei Loznitsa, 2008)](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Revue_2.jpg)

The punctum

It would be fair to say that Loznitsa’s images have a special photographic quality defined by Roland Barthes as punctum, an aesthetic punch that subtly strikes the viewer. In Camera Lucida Barthes points out a fundamental quality of a photograph, which always goes back and forth between the past, the present and the future, and between life and death too.

“I read at the same time: This will be and this has been; I observe with horror an anterior future of which death is the stake. […] This punctum, more or less blurred beneath the abundance and the disparity of contemporary photographs, is vividly legible in historical photographs: there is always a defeat of Time in them: that is dead and that is going to die. These two little girls looking at a primitive airplane above their village [...] - how alive they are! They have their whole lives before them; but also they are dead (today), they are then already dead (yesterday). At the limit, there is no need to represent a body in order for me to experience this vertigo of time defeated” (Roland Bathes, Camera Lucida).

Loznitsa’s archival films have a similar effect on the spectator. They provide the image of time and the image of the world defeated by continuous repetitions of the past. The Event presents a failed revolution, the subject which is so relevant for contemporary Russia. Blockade, a chronicle of the Siege of Leningrad during World War 2, reveals the omnipresent archetype of war and of the banality of evil. Revue is a collection of overlooked and unseen Soviet propaganda newsreels from the 50s and 60s. It is reinterpreted by Loznitsa as a commentary on new Russian ideology that borrows a lot from the Soviet mythology and uses almost the same propaganda techniques. The film explores how a fictionalized on-screen utopia can disguise itself almost as a documentary, as the makers of Soviet propaganda of the 60s effectively appropriated the free style of the Soviet films made during the period in the 1960s, known as the Thaw and commonly described as “realistic”.

Contemporary media already taught us that fiction can be more real than the actual reality, while a fake can be more authentic than a fact. In Revue Loznitsa shows the origins of the phenomenon known today as post-truth. Austerlitz, the most recent documentary of Loznitsa, examines the state of the Holocaust legacy in the times of the post-truth. However, the reference to the eponymous novel of Winfried Georg Sebald, this Proustian and deeply melancholic journey in search of lost time and lost memory, turns the film into an non-conformist attempt to retrieve the unretrievable truth about Holocaust, to seek remembrance through oblivion.

Images (1) & (3) from The Event (Sergei Loznitsa, 2015)

Image (2) de Maidan (Sergei Loznitsa, 2014)

Image (4) from Predstavlenie [Revue] (Sergei Loznitsa, 2008)

This text was originally published in Images Documentaires 88/89, July 2017.

Many thanks to Catherine Blangonnet-Auer.