Events of Images, Words and Sounds

The Films of Sergei Loznitsa

Sergei Loznitsa (1964) has referred to Zeno’s paradox of the flying arrow to describe the art of cinema. In the paradox, a flying arrow is always at rest in a specific place at any given moment. From this, Zeno concludes that motion is impossible, yet the changing positions reveal that the arrow is indeed in motion. “This paradox,” Loznitsa explains, “exists to tell us what cinema is: the illusion of movement.” Film as a physical object does not exist, he asserts. “Cinema only exists in the moment it disappears [and] when the last image ends, this is when everything rounds off. But where does it happen? In your imagination.”

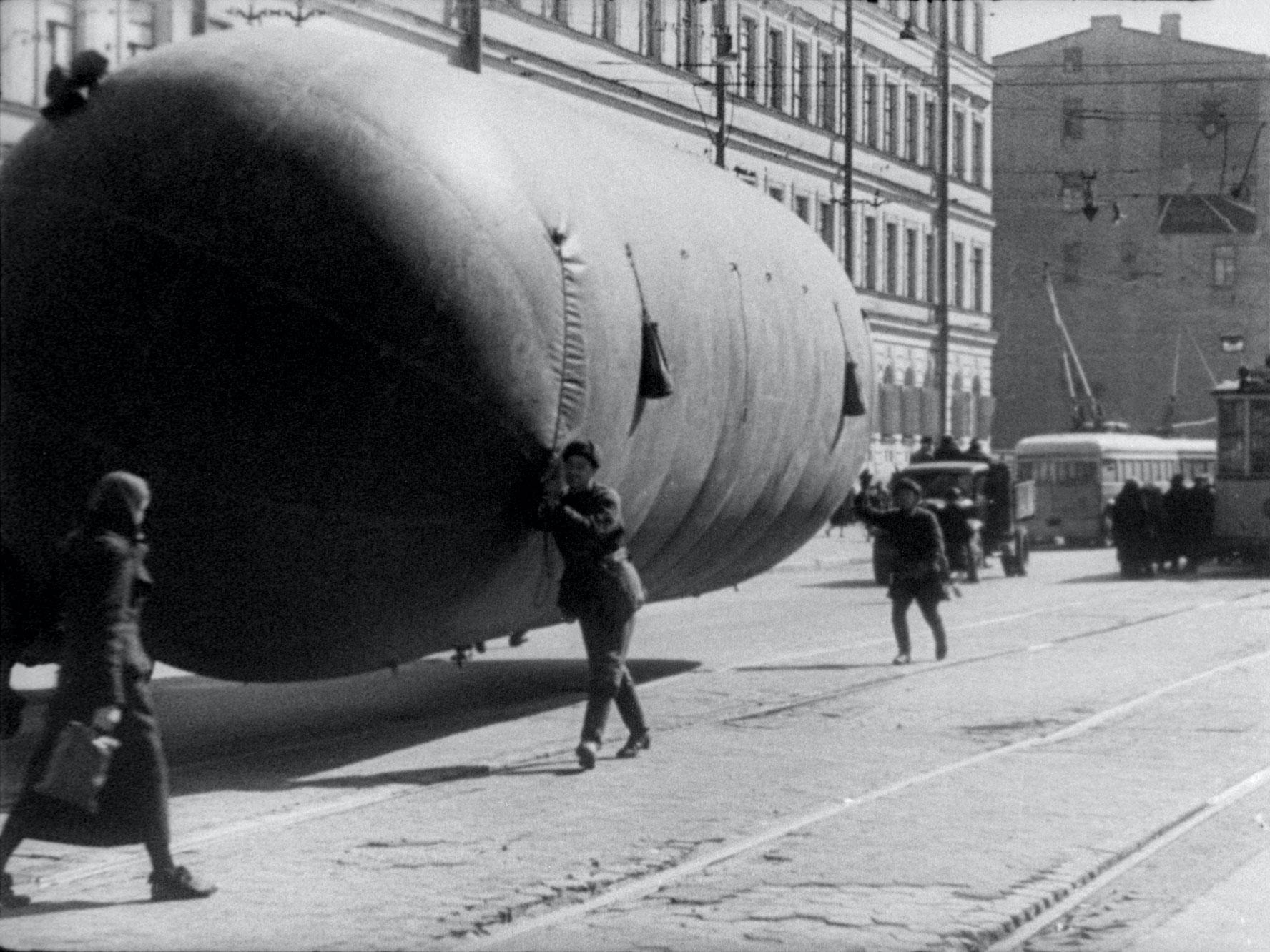

Nevertheless, finding his way in the world of cinema primarily through documentaries, Loznitsa also sees film as an instrument to describe the world. From his first documentary, Today We Are Going to Build a House (1996), his films offer incisive portraits of history – whether through everyday observations (e.g. a rural village in Life, Autumn (1999) or sleeping train passengers in The Train Stop (2000)), through the editing of found footage (e.g. the Siege of Leningrad in Blockade (2005) or the infamous Moscow show trials in The Trial (2018)), or through documenting and re-enacting contemporary events (the Ukrainian civil uprising against President Yanukovych’s regime in Maidan (2014) and more recently the fight against the Russian invasion in The Invasion (2024)). However, Loznitsa’s documentaries do not claim to show events as they are. Partly due to a carefully constructed soundtrack, precise editing and the absence of a commentary track, his films present themselves foremost as artistic creations. Reflecting on his approach, Loznitsa states, “if I could, I’d make all my films without dialogue, including my features, because I think that the substance of cinema resides in the image and the sounds.”

In 2010, Loznitsa directed his first feature film, My Joy, a dark road movie in which the seemingly random encounters of a hapless truck driver reveal the sharp contradictions that define twenty-first-century Russia. In the following years, In the Fog (2012), A Gentle Creature (2017), and Donbass (2018) followed, all three presented at Cannes.

With Zeno’s paradox in mind, we observe the remarkable place that the historical “event” holds in his work – an occurrence, a specific and significant thing that takes place, at a specific moment in time, often involving a large number of people – a mass, or a nation. The event is a point in time, a point of view of the difference between two possible worlds, but as a point itself, it cannot be perceived. It is a dead moment in time, after which things are different than before. Cinema, then, proves to be the ideal instrument to try to grasp this paradoxical non-entity, which is both nothing and something that changes everything.

Despite the strongly documentary nature of his work, Loznitsa turns the viewer of his films into a nearly spectral observer, floating through a landscape of images and sounds. His films do not seek to uncover definitive truths; instead, they propose a perspective, a way of seeing. Loznitsa presents images as they are but also how they might become or signify something else. In this sense, his films become “events” themselves – artistic arrangements of images, words and sounds, like subdued fireworks momentarily brought together in a montage of sparks, colours, and light. Loznitsa treats his images as controlled explosions as used in geological studies to uncover the world’s hidden layers. His cinema operates in paradox: nothing seems to move yet everything is in motion; nothing appears to happen yet everything unfolds. Like all great cinema, his films exist and do not exist simultaneously, straddling the realms of the real and the imaginary.

This collection is published on the occasion of the State of Cinema 2024 at Bozar, Brussels. It presents a series of texts in Dutch, French and English on Loznitsa’s oeuvre, along with film pages of his works.

Gerard-Jan Claes and Tillo Huygelen