Film Is Not a Language

Film is not, as is often thought, a language in which certain combinations of signs cover certain notions, and of which series of signs can be ordered to form a syntax.

Film knows no sign, and also no meaning. It is impossible to transform the statement “John is a scoundrel” into a combination of filmic signs. However, it is possible, for example, to use the camera to show John kicking a dog. Then we immediately understand why John is a scoundrel. Those who speak of film as a language are in fact speaking of a limited number of signs to which correspond a limited number of conditioned reactions: John kicks a dog = malice; a mother kisses a child = love; a hand shakes another hand = brotherhood. These signs have nothing to do with film per se. If John suddenly kicks a dog in the street, people will get angry without the mediation of Filmic language. Film is a means for registration, amplification and dissemination of a signal. It can only show, but: it can show everything, in all sorts of ways.

The idea of a film language with a respectable grammar goes hand in hand with maintaining the supposed laws of film. These laws define what you can and can’t do, but above all what you can’t do. They are applied by some critics, connoisseurs and quasi-connoisseurs in an invariably repressive manner (defence of...). The notions of the language of film and the laws of cinema are used by many as a reason to find bad films good and good films bad. Fortunately, there exist neither laws of cinema nor a language of film: everything is allowed.

This article was originally published in Kunst van Nu, August 1963.

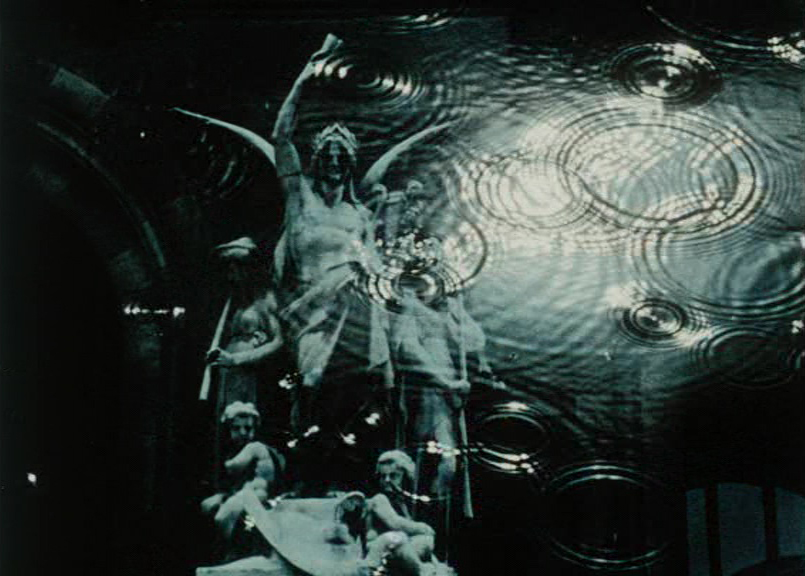

Image from Paris à l'aube (James Blue & Johan van der Keuken, 1957)