SCREENING ROOM

2021

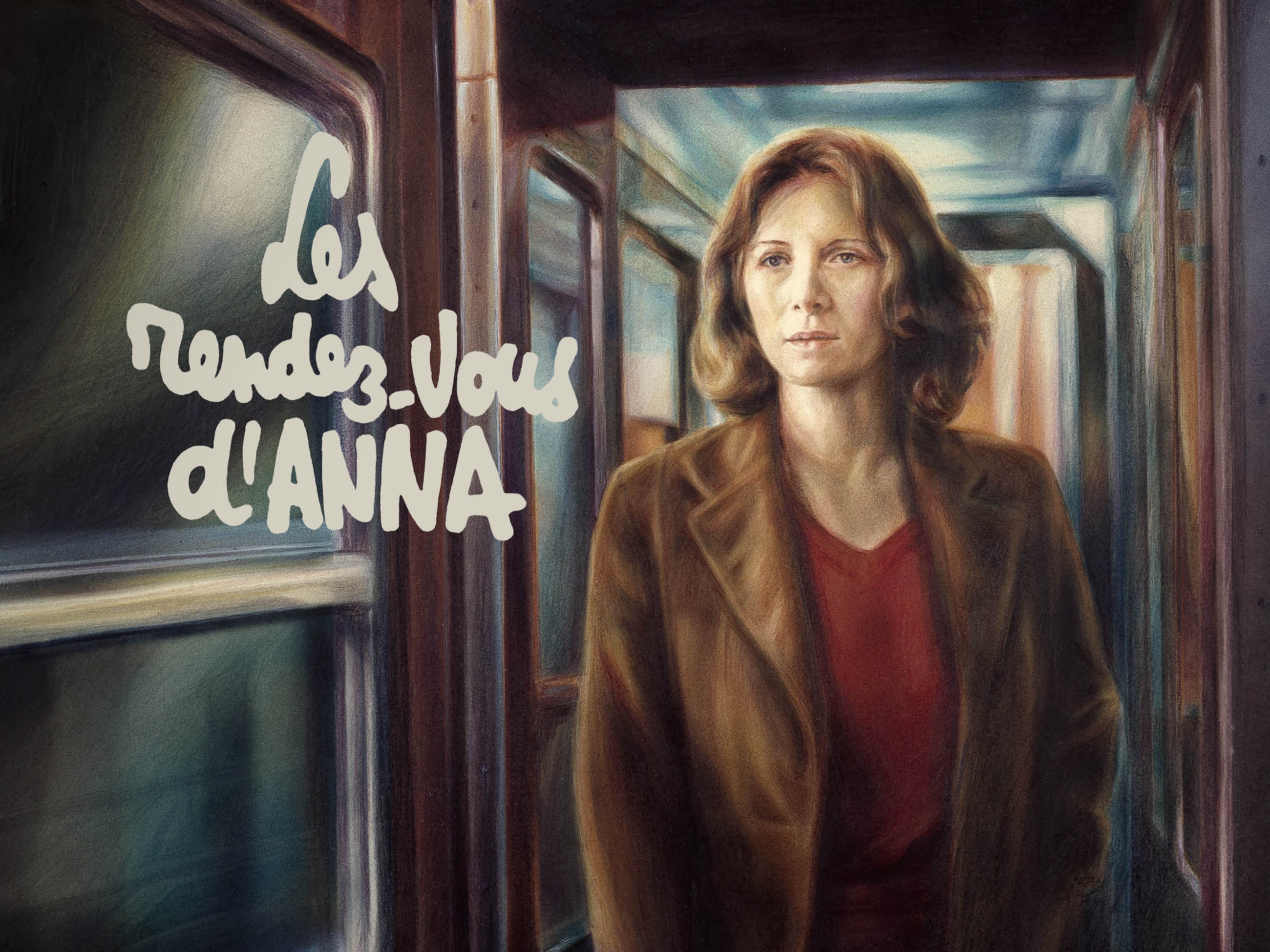

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

SCREENING ROOM

1996

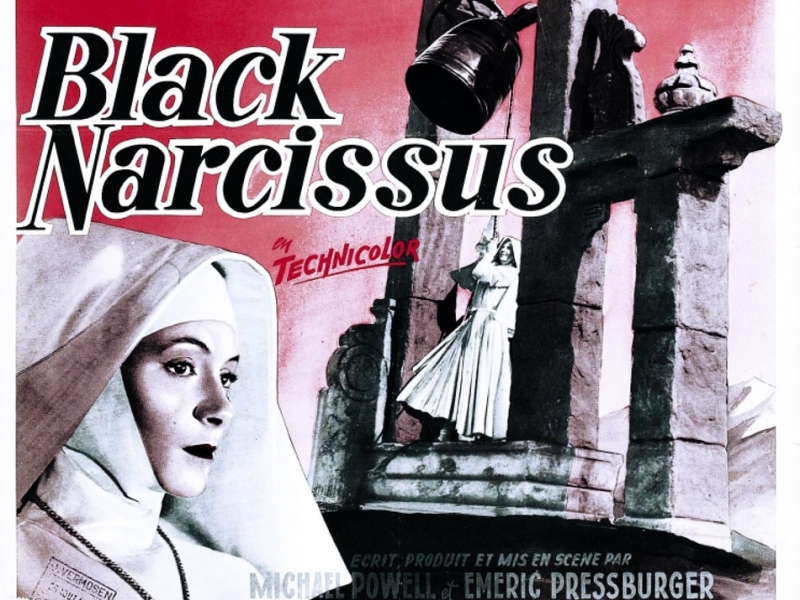

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

FILM PAGE

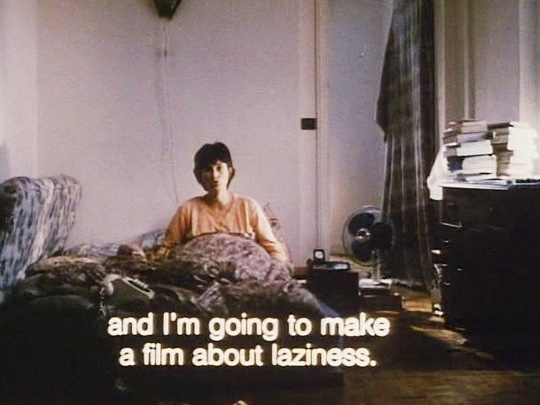

Chante Akerman

AUDIO ROOM

The fifteenth episode of The Bandwagon, Sabzian’s irregular series of film-related mixes, by editorial member of Sabzian Tillo Huygelen and photographer and film historian Hilde D’haeyere. This episode is dedicated to singing and the natural voice in Chantal Akerman’s films.

Sabzian x STROOM

AUDIO ROOM

Sabzian was invited by the Belgian music label STROOM to contribute to their radio show at The Word Radio.