Een ingang tot de cinema en het denken van Fernand Deligny

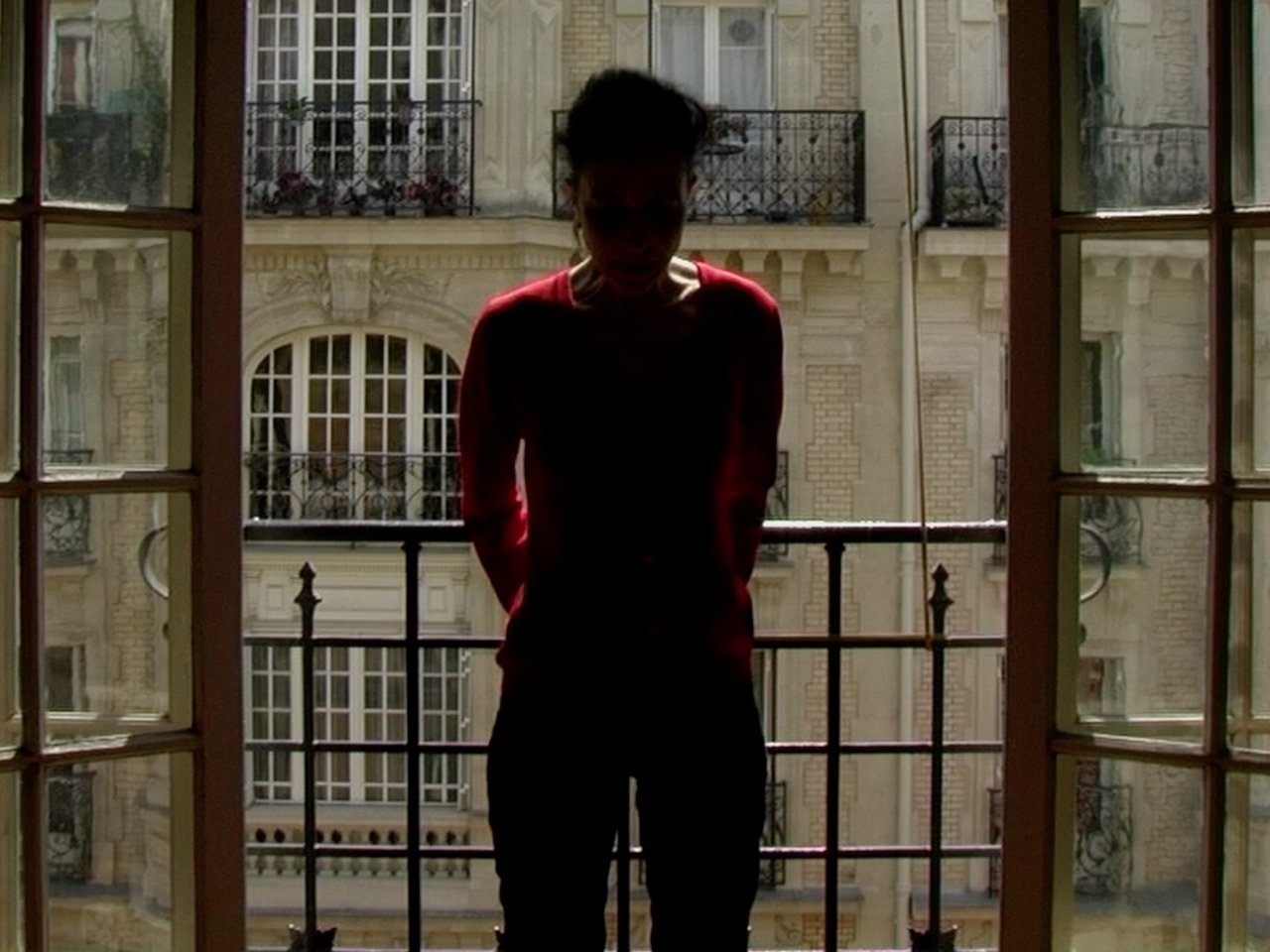

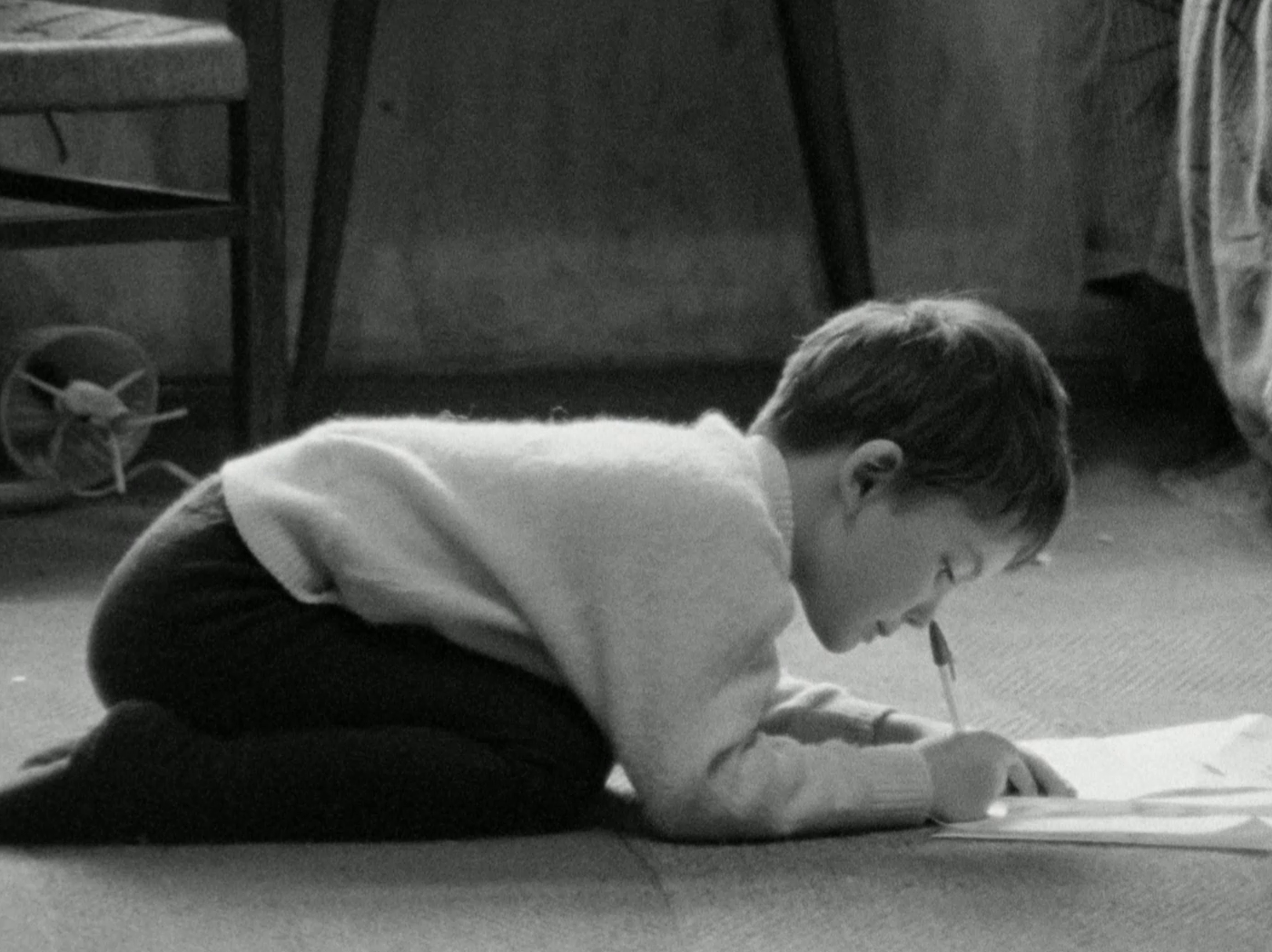

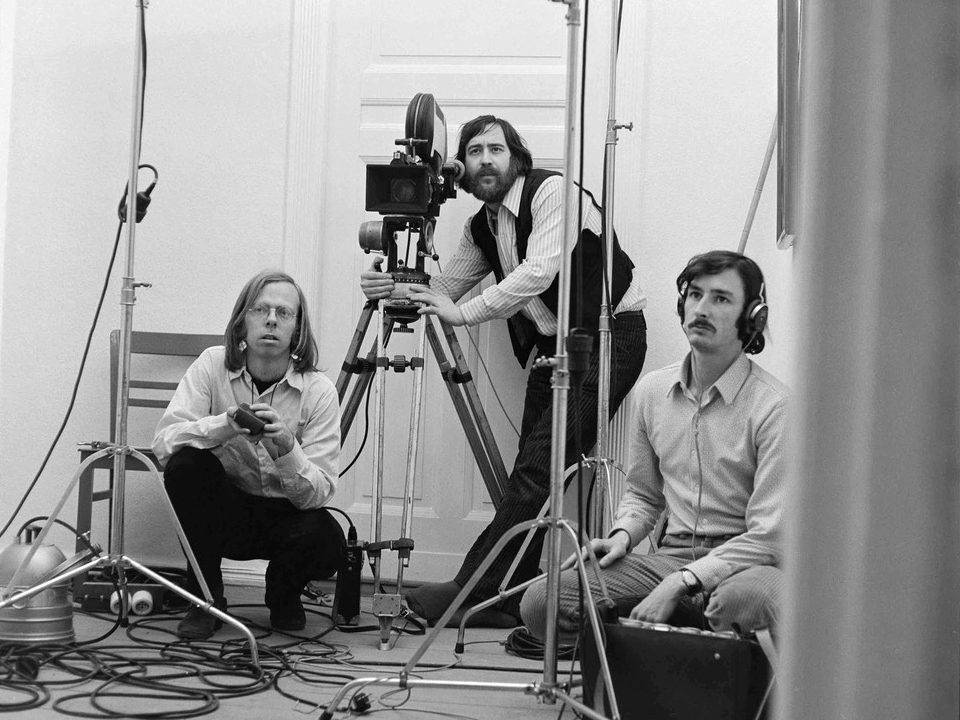

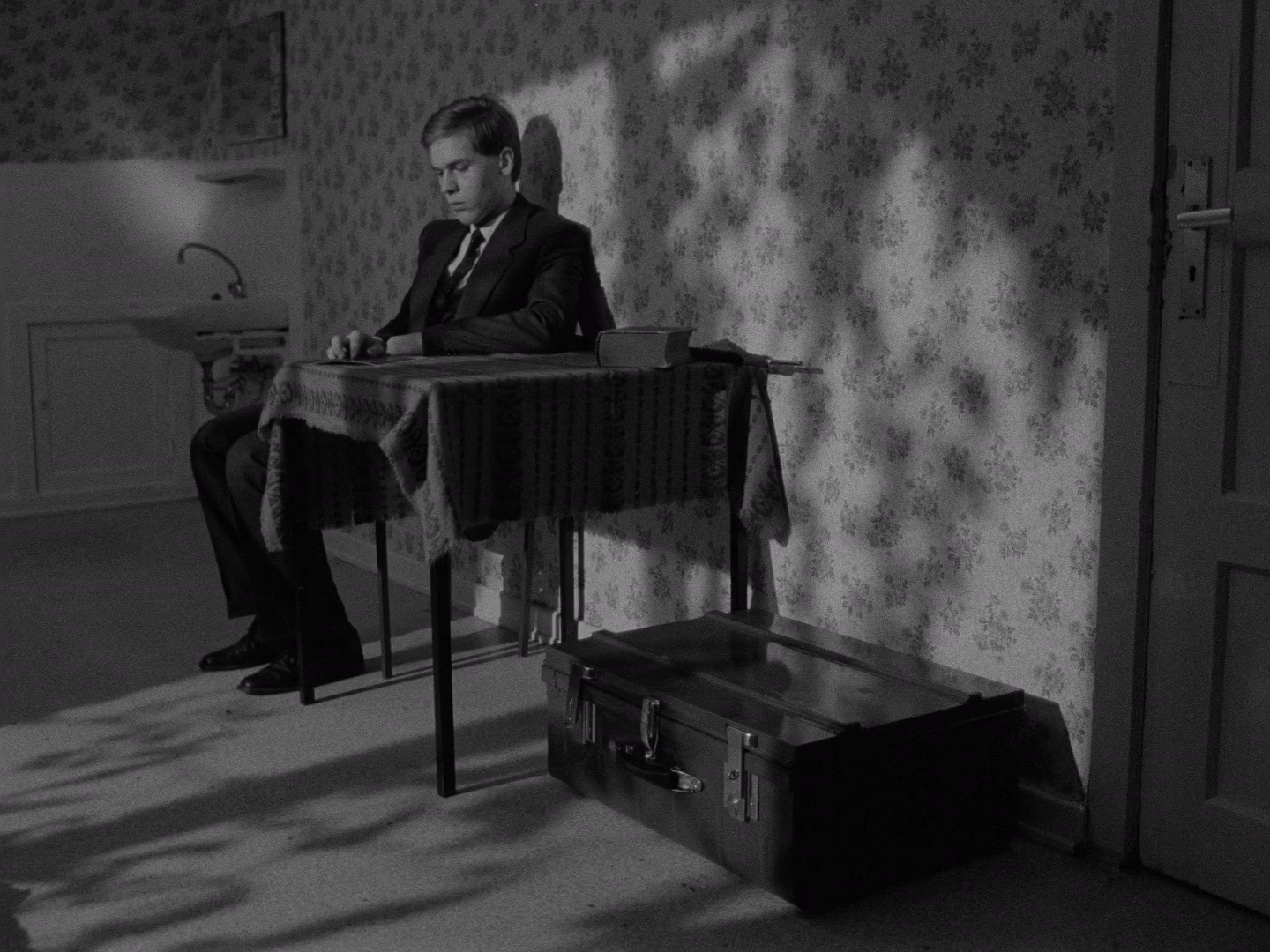

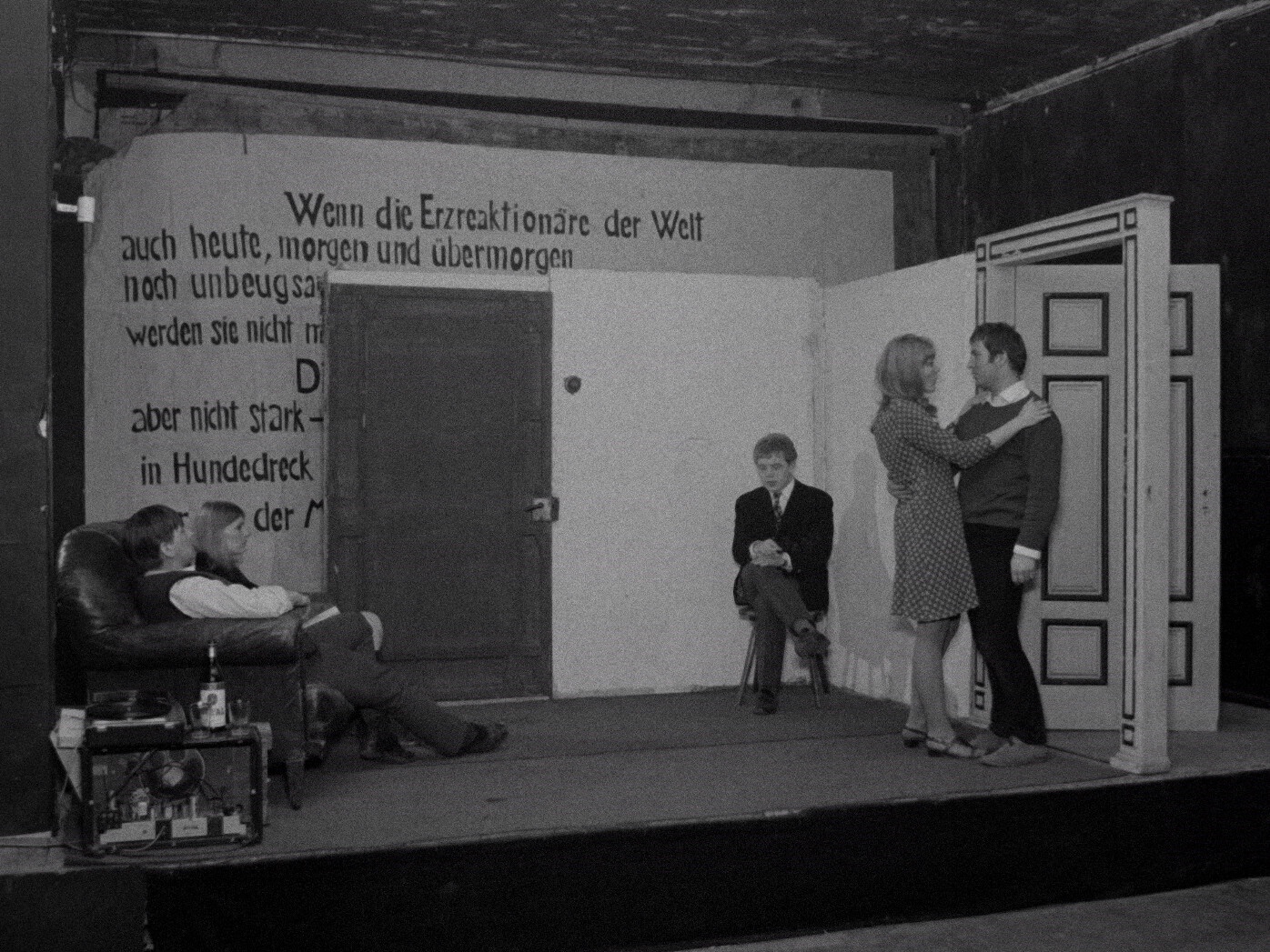

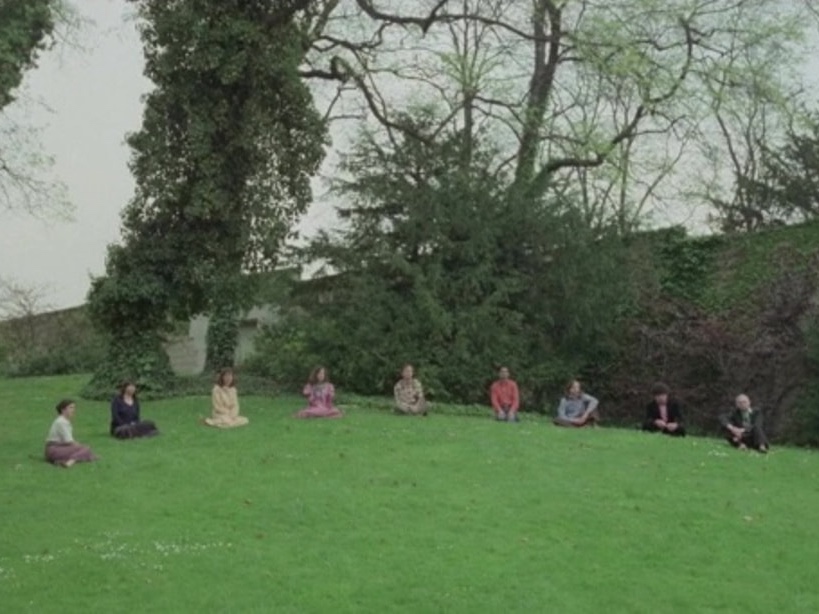

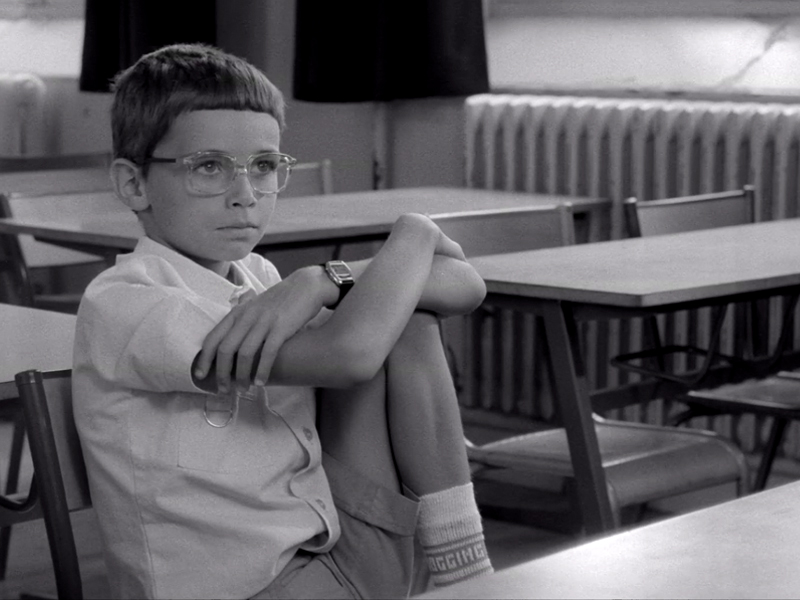

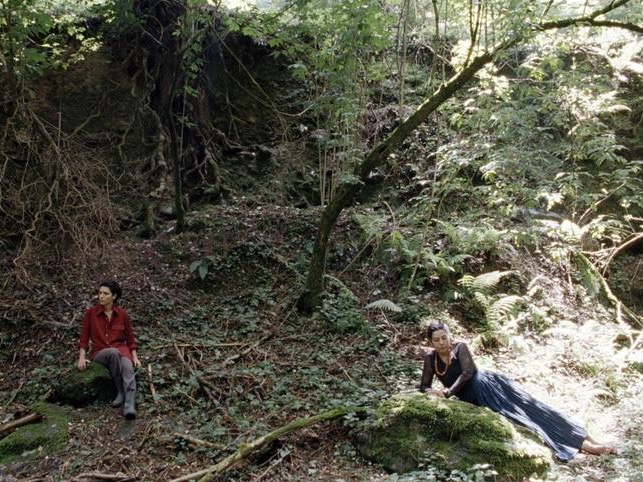

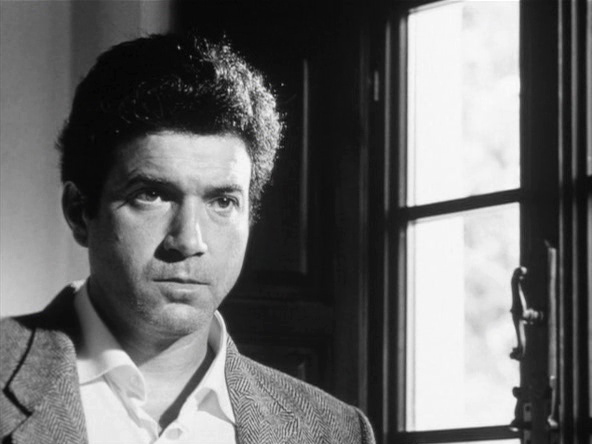

Deze film [Le moindre geste] – weerbarstig toevalsdocument, ruwe parel – lijkt te ontglippen aan elke poging tot categorisering. Hetzelfde zou je kunnen zeggen van de initiatiefnemer, Fernand Deligny (1913-1996). Deze Franse pedagoog, die een leven lang werkte met delinquente, psychisch kwetsbare en mentaal beperkte kinderen en jongeren, valt evengoed schrijver, poëet, filosoof, cineast, … te noemen. Zijn nalatenschap bevat allerlei artefacten: essays, verhalen, scenario’s, toneelstukken, sprookjes, brieven en cartografische tekeningen. Le moindre geste is de eerste van vier films die hij realiseerde in nauwe samenwerking met een wisselende entourage van medewerkers.