Texts

Every Wednesday, Sabzian publishes texts on cinema in Dutch, English or French.Chaque mercredi, Sabzian publie des textes sur le cinéma en néerlandais, en anglais ou en français.Elke woensdag publiceert Sabzian teksten over cinema in het Nederlands, Engels of Frans.

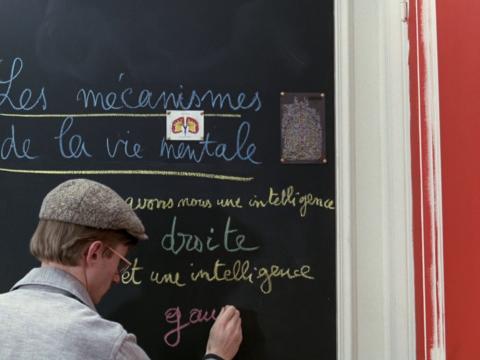

When I read the American critic Manny Farber’s text about an indispensable experimental film, I noticed that there was something extraordinary. A way of adjectivizing that which seemed ungraspable after having seen it. It was not only a matter of translating an experience but of finding the exact material to transmit that which reverberates on the screen.

Straub, who devoted his life to the voicing of German, French, Italian, and English words (and their relationship to place), must be a fellow traveller. One cannot induce divine or communist photosynthesis, but one can put words into motion. Modestly and with maximum attention, this is what Passerone and Straub do with these verses. For a few minutes they dwell on the supreme moment of illumination, asking us to match the concentration of the poet and of the speaker.

On Francis Alÿs’ Children’s Games

The concept is as straightforward as the title suggests: the collection presents the great diversity of children’s games worldwide. For Alÿs, the Children’s Games represent a seeming caesura with his previous work. Alÿs himself is no longer on view. The performative character so central to his earlier videos has here given way to a pervasive focus on the world in front of the camera. Yet the “disappearance” of Alÿs is not a radical break and results in an intensified exploration of some of the guiding principles of his oeuvre.

On the Children’s Games

I think that the children accept us because they can see that we take their game very seriously. They appreciate that. Sometimes they can see that we are not fully understanding – we, limited adults – and they will help us grasp the full logic of their actions. They want to give us the best of their skills, what Michael (Taussig) indeed calls the “mastery of non-mastery.” In all the games we filmed, the children were so much more generous than we expected. Sometimes they even protect us. They for instance make a discreet sign when they see a potential problem or danger rise on the horizon, behind the scene where the game takes place. They can see that we are so absorbed into their play that we are completely unaware of what is happening around us.

We look at Breer’s work and we begin to smile – lightly, a happy sort of smile, a happy feeling like when you see anything beautiful and perfect. It’s through an amazing control and economy of his materials that he achieves this; through the elimination of all the usual emotional, personal, biographical, sick material; by not giving in to temptations.

I am happy that Robert Breer got some recognition. I saw his new film, 69, and it’s so absolutely beautiful, so perfect, so like nothing else. Forms, geometry, lines, movements, light, very basic, very pure, very surprising, very subtle. Breer’s films do not get much public acclaim. His shows are not among the heavily attended. His films attract no noise. But they are among the best films made today anywhere. A new film by Robert Breer is an important event.

An Interview with Robert Breer

Do you know the joke about the two explorers who get captured by the natives and tied to trees? The chief tells the first one, “You have two choices: death or ru-ru.” The explorer thinks a bit and says, “Well, ru-ru.” “Wise decision,” says the chief who unties him. Then the whole tribe beats him up and abuses him sexually and completely destroys him and throws him down dead in front of the other explorer. The chief asks the second explorer which he prefers, death or ru-ru? The second explorer is very shaken up by what he’s seen and finally says, “Death.” And the chief says, “Very wise decision – death it is – but first, a little ru-ru.” I love that joke. In my work there’s always a little ru-ru.

I guess I still think of myself as a painter just using film. Film is very liberating for me, the idea that I could slide into art. Film is in motion, life is in motion. It seemed to me that if I could kind of sidle up to art by being in a fluid medium rather than having to declare “this is it for ever and ever”. It appealed to me in that way.

William Friedkin (1935-2023)

The truth is that there are fewer big misanthropes in film than Friedkin. He just rarely seems to have a decent opinion of other human beings, not that he is especially nicer about himself: his autobiography starts in a self-defeating manner, listing a series of personal mistakes, beginning with the tale of how a young Jean-Michel Basquiat gifted him a painting he promptly threw in the trash because, well, he wasted so much money that day. One suspects the reason he loved staging car chases was because it allowed him to completely downplay the human element. Machines in the environment might be the ideal form for Friedkin’s worldview.

De destructie zit niet in hem maar in de buitenwereld, waarvan onze held de aantrekkingskracht zo goed kent dat hij zich moeiteloos laat meeslepen. De scène waarin Arnaud rondjes draait op zijn scooter als op een stier krijgt door de klassieke muziek de allure van een gevecht met de wereld. Portier ziet hierin een serene schoonheid en speelsheid. Achter zijn kleine misdrijven schuilt de gratie van een stierengevecht.

Een gesprek over Soy libre van Laure Portier

Dat is wat ik leuk vind aan cinema: het is iets fysieks. Voor mij moet het lichaam reageren vóór de geest: als mijn lichaam het begrepen heeft, zal de rest wel volgen. Arnauds verlangen naar vrijheid is fysiek. Om dat te begrijpen hoef je alleen maar op zijn scooter te stappen, waarmee hij zonder helm op volle snelheid rondrijdt. Wie wil dat niet ervaren?

On the Cinema of Wes Anderson

Whereas in earlier films like The Royal Tenenbaums I felt like I was playing along with the film because there was the freedom to look around and establish connections, actively puzzling together the many rooms and rebuses, Asteroid City is playing by itself, all alone. I’m watching a music box unwinding at double speed, but any sense of a space, any notion of time has disappeared. Apathetic fatigue is the result.

Over de cinema van Wes Anderson

Waar ik in eerdere films zoals The Royal Tenenbaums het gevoel had met de film mee te spelen omdat er een vrijheid was om rond te kijken en verbindingen te maken, actief de vele kamers en rebussen in elkaar te puzzelen, speelt Asteroid City nu zichzelf, helemaal in zijn eentje. Ik kijk naar een speeldoos die zich op dubbele snelheid afwindt, maar er is geen zweem van een plaats, noch een notie van tijd meer. Apathische vermoeidheid is het gevolg.

On the Inability to Deal with Old Forms

Sometimes images present themselves with the force of necessity – or should I say inevitability? I naturally saw a film like Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers coming – I think in retrospect! – for quite some time. Sooner or later, all those images lying around will become entangled.

Over het onvermogen met oude vormen om te gaan

Soms doen beelden zich voor met de kracht van het noodzakelijke – of moet ik zeggen van het onvermijdelijke? Een film als Natural Born Killers van Oliver Stone zag ik natuurlijk – denk ik achteraf! – al langer aankomen. Vroeg of laat moeten al die rondslingerende beelden bij elkaar klitten.

It is a film that entices one to take endlessly long detours and twists and steps forward and backward in an atmosphere of uncertainty about its value and meaning. Every now and then, there are films that fall right into the pipeline of the critic’s letter stream: films on an (almost physically) identifiable “important” theme, in this case “Fascism”, but which have also built in a series of ambiguous shadows and mirror images, so that everyone is left searching for the filmmaker’s final “statement” on his subject. Quite strikingly, importance and vagueness go hand in hand.

Het is een film die ertoe verleidt eindeloos lange omwegen en kronkels en stapjes vooruit en achteruit te maken in een sfeer van ongewisheid over zijn waarde en betekenis. Zo nu en dan zijn er films die recht in de pipeline van de letterstroom van de criticus zitten: films over een (bijna fysiek) aanwijsbaar “belangrijk” thema, in dit geval “Het Fascisme”, maar die tegelijk een reeks dubbelzinnige en ambigue schaduwen en spiegelbeelden inbouwden, zodat iedereen naar de uiteindelijke “uitspraak” van de cineast over zijn onderwerp zit te zoeken. Belangrijkheid en onduidelijkheid gaan treffend genoeg samen.

There is a rightness, an inner consistency, and an absence of moral hesitation that make Visconti’s films breathtakingly modern. It is our sense of physicality that we see at work on the screen: a theatrical nudity, an artificial naturalness, a perverse spontaneity. It is important to think both contradictory terms together, because modern physicality resides in this very tension, their unresolvedness, our continuous journey between both poles.

Er is een juistheid, een innerlijke consequentie, een afwezigheid van morele verpinkingen die Visconti’s films adembenemend modern maken. Het is ons gevoel van lichamelijkheid dat we op dat scherm werkzaam zien: een theatrale naaktheid, een artificiële natuurlijkheid, een perverse spontaniteit. Het is belangrijk beide contradictorische termen samen te denken, want het is in hun spanning, in hun nimmer besliste keuze, in onze voortdurende reis tussen beide polen, dat de moderne lichamelijkheid zich situeert.

Het is ongelooflijk hoe verblindend de slogan “realisme” in onze cultuur werkt. Het is een zelfdestructief, zelfreducerend mechanisme. Zodra je die slogan hanteert, zodra je dat programma aanhangt, zodra je dat interpretatieschema hanteert, glijdt je onweerstaanbaar van de ene “basic reality” naar de andere. Je komt onweerstaanbaar de glijbaan afgegleden, maar je bereikt nooit het eindpunt van een “werkelijk realisme”, je komt nooit bij de ultieme realiteit. Realisme lijkt op een zen-denk-opgave, die je gedachten in een onontwarbaar net inspint. Om eruit te komen moet je een soort kwalitatieve sprong maken, uit de “ban” van het realisme. Want het is een sofisme, gezichtsbedrog.

It’s incredible how dazzling the effect of the slogan “realism” is in our culture. It’s a self-destructive, self-reducing mechanism. As soon as you wield that slogan, as soon as you adhere to that programme, as soon as you use that interpretational framework, you slide irresistibly from one “basic reality” to another. You irresistibly come sliding down the slide, never reaching the end point of a “true realism”, never arriving at the ultimate reality. Realism resembles a Zen thinking task, which spins your thoughts into an inextricable net. To get out of it, you have to take a kind of qualitative leap, out of the “spell” of realism. Because it’s sophistry, an optical illusion.

In the 1950s, the new American actor was formed by the Actor’s Studio. At the end of the 1960s, the next generation of actors arrived, manifesting themselves alongside established Hollywood actors (from Bronson and Heston to Newman, from Reynolds to Scott) in very different kinds of films. The common denominator of Al Pacino, Dustin Hoffman, Jack Nicholson, Robert de Niro, and Richard Dreyfuss? They aren’t introverted or haughty like Actor’s Studio actors: they’re exuberant, dynamic, aggressive. They’re not masochistic (Dean, Brando) but sadistic (Dreyfuss and Nicholson). They’re not neurotic but psychotic (De Niro). They aren’t looking for recognition but confirmation. They aren’t playing for the audience but for themselves.

In de jaren vijftig werd de nieuwe Amerikaanse acteur gevormd door de Actor’s Studio. Op het einde van de jaren zestig trad een volgende generatie acteurs aan, die zich naast de gevestigde Hollywoodspelers (van Bronson over Heston tot Newman, van Reynolds tot Scott) in een heel ander soort films manifesteerden. De gemene deler van Al Pacino, Dustin Hoffman, Jack Nicholson, Robert de Niro, Richard Dreyfuss? Ze zijn niet introvert of hautain als de Actor’s Studio-acteur: ze zijn uitbundig, dynamisch, agressief. Ze zijn niet masochistisch (Dean, Brando), maar sadistisch (Dreyfuss en Nicholson). Ze zijn niet neurotisch, maar psychotisch (De Niro). Ze zijn niet op zoek naar (h)erkenning, maar naar bevestiging. Ze spelen niet voor het publiek, maar voor zichzelf.

The filmmaker lives in his films. His decisions don’t flawlessly follow an academic ideal but flawlessly follow what he has to say. It’s not without vulgarity, demagoguery or overemphatic naturalism, but the film takes all this in unadulterated. And I take it with both hands and bring it to my eyes, which greedily indulge in it. How many years has it been since I have seen such vital images?

De cineast leeft in zijn films. Zijn beslissingen zijn niet feilloos volgens een academisch ideaal, maar feilloos naar wat hij te vertellen heeft. Het is niet zonder vulgariteit, niet zonder demagogie, niet zonder overnadrukkelijk naturalisme, maar de film neemt dit alles ongekuist in zich op. En ik neem het met beide handen en breng het naar mijn ogen, die er zich gulzig aan te goed doen. Hoeveel jaren is het al niet geleden dat ik zulke vitale beelden zag?

Lukas Dhont’s Close

Close drives home the paradox of a postnational national identity. Whereas Belgian cosmopolitanism in films like Le fidèle and Girl is still somewhat anchored in a cultural reality, Close deliberately leaves existing Belgium behind. At the crossroads between the local and the global, the film oscillates between hyper-Belgian and hyper-universal. The result is an abstract, postnational Belgian identity, stripped of cultural specificity. The film merely expresses a make-believe image of Belgium and leaves out its concrete complexity. In the absence of a meaningful reference to the existing country, the representation of Belgium becomes a self-referential simulacrum whose meaning is limited to the diegetic space.

Lukas Dhonts Close

Close drijft de paradox van een postnationale nationale identiteit op de spits. Waar het Belgisch kosmopolitisme in films als Le fidèle en Girl nog enigszins verankerd is in een culturele realiteit en een reële sociale werkelijkheid reflecteert, keert Close het bestaande werkelijke België de rug toe. Op het kruispunt tussen het lokale en het globale schommelt de film tussen hyperbelgisch en hyperuniverseel. Het resultaat is een abstracte, postnationale Belgische identiteit, ontdaan van culturele specificiteit. De film drukt slechts een schijnbeeld van België uit en laat de complexiteit van het concrete België buiten beeld. Bij gebrek aan een betekenisvolle verwijzing naar het bestaande, wordt de representatie van België een zelfverwijzend simulacrum waarvan de betekenis zich beperkt tot de diëgetische ruimte: een ideëel België.

On the Filming of Albert Serra’s Pacifiction

Shot in Tahiti, Albert Serra’s film Pacifiction, which premiered at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival, stars Benoît Magimel in the role of a high commissioner representing the French government. For Pacifiction, Serra once again collaborated with cameraman and editor Artur Tort. Tahiti is staged in bright colours, as an elusive, magical place. The camera moves at high speed on a speedboat, travels in a small plane and bobbles up and down on the waves among surfers. The images are at the same time wild and uncluttered, giving the film a rare energy. Sabzian spoke to Tort about his collaboration with Serra and the process behind Pacifiction.

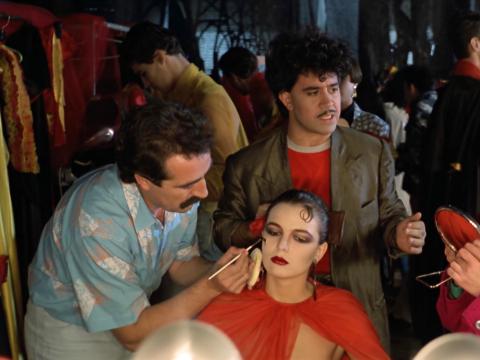

Matador (1986) and Átame! (1989)

Almodóvar’s beautiful films counterbalance the dominant academicism. Not the story, not the script, not the dialogues determine his films, nor does the preciosity of the image. The power of the films lies in the acting, the physical interaction between the actors confronted with the camera and direction. The actors play in front of a camera that always gives them the freedom to complement, encourage, correct and ironise each other.

Matador (1986) en Átame! (1989)

De prachtige films van Almodóvar vormen het tegenwicht voor het dominante academisme. Niet het verhaal, niet het script, niet de dialogen bepalen zijn films, evenmin de preciositeit van de beeldvorming. De kracht van de films is gelegen in de manier waarop de acteurs spelen, hun lichamelijke interactie in confrontatie met camera en regie. De acteurs spelen voor een camera die hen voortdurend de vrijheid schenkt om elkaar aan te vullen en aan te moedigen, te corrigeren en te ironiseren.

A film that is not at all what it claims to be at face value, a success that is not actually a success, an audience that is merely programmed. A puzzle that never really fits together and which everyone nonetheless claims to form a nice pattern. All the pieces are there, but the figures on it do not form a whole. Everything is wrong, the nose to the feet, the hands to the head. And yet you think, what a beautiful hand and what beautiful eyes!

Een film die helemaal niet is wat hij at face value beweert te zijn, een succes dat eigenlijk geen succes is, een publiek dat alleen maar geprogrammeerd is. Een puzzel die eigenlijk nooit in elkaar past en waar iedereen toch van beweert dat hij een mooi patroon vormt. Alle stukjes zitten er wel in, maar de figuurtjes erop worden maar geen geheel. Alles zit verkeerd, de neus bij de voeten, de hand aan het hoofd. En toch denk je: wat een mooie hand en wat een mooie ogen!

Men beweert dat Chaplin in Modern Times kritiek levert op onze samenleving en veel mensen zullen wel weer de indruk hebben dat hij ook voor deze tijd nog belangwekkende dingen zegt. Maar als je goed kijkt, heeft hij het over een even abstracte maatschappij, over een even abstracte en decoratieve techniek als Fritz Lang in Metropolis.

People claim that, in Modern Times, Chaplin is criticising our society, and many people will no doubt have the impression that he is saying interesting things even for our times. But if you look closely, he is talking about a society as abstract, about a technique as abstract and decorative as Fritz Lang in Metropolis.

Spiritual Gentlemen and Natural Ladies

The centre of Dreyer’s films does not appear directly. He marks its edge. The images are only scraps of the infinite, the unformed, the possible, hieratic and rigid, to demonstrate their limitations. In Dreyer films, you can never identify with just one character; heroes and villains do not exist. The struggle is more cosmic, but not ahistorical. With him, orders collide, or rather order with disorder.

De innige verstrengeling van utopie en pessimisme, zo karakteristiek voor Godards late werk, ligt reeds besloten in Un film comme les autres (1968), een typevoorbeeld van zijn activistische cinema.

On Soy libre (Laure Portier, 2021)

Soy libre transcends the merely biographical. Arnaud’s concrete life acquires a shimmering abstraction by becoming part of a history. In this sense, Soy libre is a classic story, a contemporary life chronicle reminiscent of the work of John Ford, whose films show that human resistance is largely determined by the social environment. A guide in a turbulent world, Arnaud seeks an answer to the question of what makes life worth living.

Roma, Fellini’s film uit 1972, toont een collage van groteske scènes die zich afspelen in Rome op verschillende momenten in de twintigste eeuw. Op een gegeven moment in de film zien we beelden van de nachtelijke straten en pleinen van Rome. Er klinken voetstappen die dichterbij komen, een schaduw strijkt over een gevel en dan wandelt een in het zwart geklede vrouw langs een rij huizen het beeld in.

His films are irritating, off-putting, somewhat repulsive. Admirers of his work should not brush off this negative, backward contact between Fassbinder and his audience but rather depart from it. In this oeuvre, an aesthetic of irritation is essential.

Zijn films irriteren, stoten af, zijn een beetje weerzinwekkend. Bewonderaars van zijn werk moeten dit negatieve, averechtse contact tussen Fassbinder en zijn publiek niet wegpraten, maar er juist van vertrekken. In dit oeuvre is een esthetiek van de irritatie essentieel.

On Tout va bien by Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin

Tout va bien is again a film that is addressed to me as well. Contact has been restored. I wasn’t really expecting that anymore. I feared Godard had collapsed under May ’68, which functioned as a late adolescence and identity crisis for the generation of the 1950s. Tout va bien proves that Godard used all those years well, that he worked and subjected himself to an intense, painful reconstruction.

Over Tout va bien van Jean-Luc Godard en Jean-Pierre Gorin

Tout va bien is opnieuw een film die ook aan mij is gericht. Het contact is hersteld. Ik verwachtte dat eigenlijk niet meer. Ik vreesde dat Godard bezweken was aan mei ’68, die voor de generatie van ’50 functioneerde als een late adolescentie- en identiteitscrisis. Tout va bien bewijst dat Godard al die jaren goed gebruikt heeft, gewerkt heeft, zichzelf aan een intense, pijnlijke reconstructie heeft onderworpen.

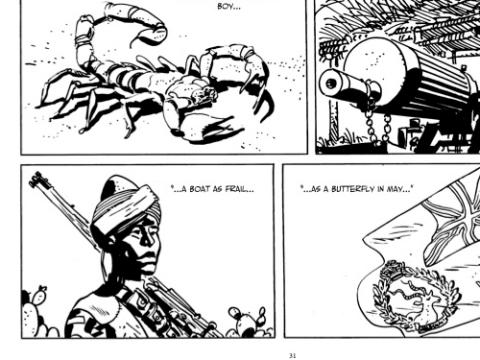

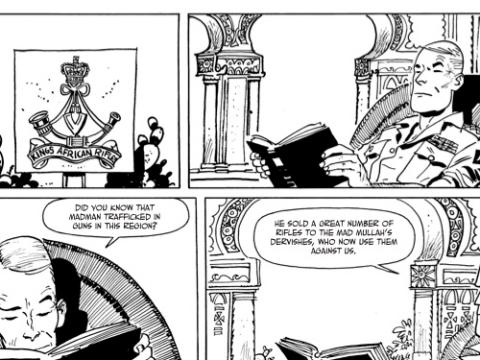

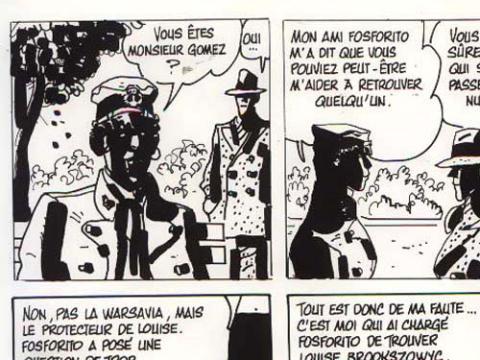

I started by skipping over Pratt’s pages, finding his drawings “ugly”. However, at some point I began to pore over them obsessively, trying to figure out why they disturbed me so much. I have no doubt that the process out of which I would emerge a film critic was put in motion at that time. There was one passage that particularly stirred me: the opening two pages of a story called The Coup de Grace. The first page consisted of what I hadn’t yet learnt to recognize as a montage sequence – built on the principle of counterpoint between image and text.

Initieel sloeg ik de pagina’s van Pratt over omdat ik zijn tekeningen “lelijk” vond. Op een gegeven moment begon ik ze echter obsessief te bestuderen en probeerde ik erachter te komen waarom ze me zo in de war brachten. Ongetwijfeld werd daar het proces in gang gezet waaruit ik als filmcriticus tevoorschijn zou komen. Er was één passage die me bijzonder beroerde: de eerste twee pagina’s van een verhaal dat The Coup de Grace heette. De eerste pagina bestond uit wat ik nog niet wist te herkennen als een montagesequentie – opgebouwd op basis van het contrast tussen beeld en tekst.

Au début, je sautais les pages de Pratt, dont je trouve les dessins « moches ». Mais à un moment, je suis mis à les étudier de façon obsessionnelle, en essayant de comprendre pourquoi ils me dérangent tant. Aucun doute, c'est à ce moment-là que s'est enclenché le processus qui fera de moi un critique de cinéma. Il y un passage qui me touche particulièrement : les deux premières pages de l’histoire Le coup de grâce. La première page consiste en ce que je n'avais pas encore appris à reconnaître comme un montage-séquence – construite sur le principe du contrepoint entre l'image et le texte.

Omtrent een schoolvertoning van La chinoise

Hoe gedateerd is La chinoise? Ik zie een film die zich tegelijk in en buiten zijn eigen tijd begeeft en daarom niet tijdloos is maar blijvend hedendaags kan zijn. De studenten lijken daarentegen een signaal uit een vervlogen tijd te ontvangen, uit een wereld voorgoed afgesloten van het leven in deze tijd. Zij incasseren een Franse arthouse-prent van lang geleden, enkel ontcijferbaar voor het getrainde oog en oor van cinefiele babyboomers. Als betreft het een geheimtaal uit een ten ondergegane cultuur in een verafgelegen land.

Wat Mekas als geen ander tastbaar maakte, is dat een moment capteren, op film of op video, een immanente spiritualiteit kan blootleggen in de werkelijkheid. Zelfs kleine, alledaagse gebeurtenissen kregen bij hem een quasi subliem karakter.

An Interview with Raoul Servais

The very first box of colour pencils Raoul Servais received as a child made a profound impression on him. Young Raoul considered the act of creating something on paper to be a real miracle. The second experience that marked him was the first time he watched Felix the Cat moving on a silver screen. This sense of marvel and the mystery of what makes an animated film fuelled his passion. Servais: “In those days there were no schools to learn the tricks of the trade, nor was there any literature available. I visited animation studios in Paris and Antwerp but they were very secretive about the technique as they feared the competition. They even went so far as to prohibit film technicians from talking to the animation team and vice versa so nobody would know the entire process from A to Z. After a lot of crazy experiments and a lot of tinkering around, I finally figured out how to make my own animated film.”

Een interview met Raoul Servais

De allereerste doos potloden die Raoul Servais als kind kreeg, liet een diepe indruk op hem na. Iets scheppen op papier was een wonder voor de kleine Raoul. Ontdekken hoe Felix de Kat bewoog op het scherm, was het tweede wonder. De verwondering en het mysterie van een animatiefilm wekten zijn passie. Servais: “Er bestonden nog geen scholen om het vak te leren en er was geen literatuur. Ik bezocht tekenstudio’s in Antwerpen en Parijs, maar zij hielden de techniek geheim uit angst voor concurrentie. Het ging zelfs zo ver dat de filmtechnici geen contact hadden met de tekenaars en andersom. Ze wilden vermijden dat iemand het volledige proces zou kennen. Na veel sukkelen en dwaze experimenten ontdekte ik hoe je een animatiefilm moest maken.”

Entretien avec Raoul Servais

La toute première boîte de crayons qu’il a reçue quand il était enfant a profondément marqué Raoul Servais. Imaginer quelque chose et le voir prendre forme sur le papier tenait du miracle pour ses yeux d’enfant. Découvrir comment étaient créés les mouvements de Félix le Chat à l’écran fut une autre source de fascination. L’émerveillement et le mystère entourant les films d’animation ont semé les graines de sa passion. Servais : « Il n’existait pas d’école pour apprendre ce métier, ni de documentation. J’ai visité des studios d’animation à Anvers et Paris, mais ils ne révélaient pas leurs techniques par crainte de la concurrence. C’était à un point tel que les techniciens d’animation n’avaient aucun contact avec les dessinateurs et inversément pour éviter qu’une même personne connaisse l’ensemble du processus. Après de nombreuses expériences, j’ai fini par découvrir comment réaliser un film d’animation. »

What are we to make of Tár? Some facts are all too familiar by now: before October 2022, the American director Todd Field held moderate renown as a fringe director with two niche movies on his CV. His debut, In the Bedroom (2001), and the later Little Children (2005) showed a quiet yet smart auteur taken to grand gestures with minimal risk. After 2005 he set his sights on “material that was probably very tough to get made,” as he described it, traipsing to the margins with pilots based off Joan Didion and Jonathan Franzen. A fifteen-year-long hiatus opened itself. In late 2022, Tár assured Field’s notoriety for cultural critics over a mere two-month span. His account of a star classical music conductor felled by a #MeToo case invites commentary – or at least invites something.

Todd Fields Tár

Wat te doen met Tár? Tot voort kort was regisseur Todd Field een kleinere maker met enkele nichefilms op het curriculum vitae. Werken als In the Bedroom (2001) en Little Children (2005) lieten een bedeesde maar slimmige auteur zien die de grote gebaren niet schuwde maar verantwoorde risico’s nam. Daarna beet hij zich vast in projecten met een (naar eigen zeggen) laag haalbaarheidsgehalte en trappelde ter plaatse met series rond Joan Didion en Jonathan Franzen. Een hiaat van vijftien jaar opende zich. Nu verzekert Tár op een paar maanden cultuurkritische beruchtheid. Fields’ relaas van een sterdirigente die door een MeToo-zaak wordt geveld, noopt tot spreken – of alleszins tot iets.

Jerzy Skolimowski, geliefd omwille van zijn in Brussel gefilmde New Wave-wervelwind Le départ (1967), heeft zich op latere leeftijd nog aan een ezel verbrand. De ezel als filmfiguur is gevaarlijk en vergt (over)moed: in 1967 verfilmde Robert Bresson het leven van een ezel, en eigenlijk dat van ons allemaal. De stille, tragisch en toch banale stappen door de tijd van een levend wezen, toevallig een ezel.

Gesprek met Hannes Verhoustraete over Broken View

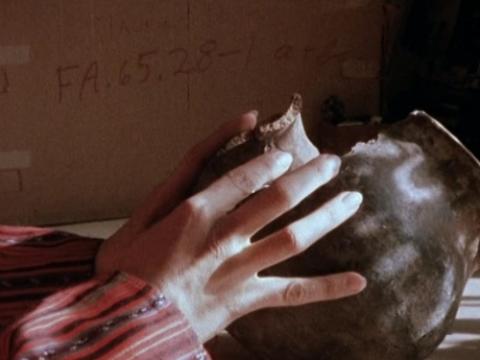

Op 2 april 2023 gaat de nieuwe langspeelfilm Broken View van Hannes Verhoustraete in première op het Courtisane-festival in Gent. Broken View vormt in navolging van Verhoustraetes eerste langspeler Un pays plus beau qu’avant een verdere exploratie van de beeldengeschiedenis van de voormalige Belgische kolonie Congo. Broken View navigeert door deze koloniale beeldenproductie door middel van montage, collage en assemblage om tot een hercontextualisering te komen van de Belgische koloniale geschiedenis. Net zoals in zijn vorige films vertrekt Verhoustraete van een essayistische schriftuur die verschillende perspectieven verknoopt en van de verhouding tussen beeld en beeldenmaker steeds een spel van toenaderen en afstandnemen maakt.

Where am I going to put my body? The question casts a shadow over the slowed-down, branched-off realities in Milestones. The bodies that no longer find a place in the service of the revolution or the ending of the war are now directing the revolution (or the war) at themselves and the bodies around them. The film’s leitmotif is to be found in the constant negotiation between the personal and the political. We see the characters searching for new forms of coexistence, alternative ways of raising their children, a new physicality, sexuality, love. The baby boomers have turned thirty, and for many of them a time has come in which the meaning of an individual life gains the upper hand over collective political projects.

In Triangle of Sadness’s deterministic portrayal of humankind and the world, capitalism is not only the best but also the only possible social order. Even on a desert island, an enclave outside the dialectics of history, it covers the entire ideological horizon. Östlund's world – in which the players change places but the game remains the same – visualises the liberal and anti-revolutionary argument that the revolution of the proletariat inevitably leads to a continuation of the exploitation of an oppressed bourgeoisie by a vengeful working class.

In het deterministische mens- en wereldbeeld van Triangle of Sadness is het kapitalisme niet alleen de beste, maar ook de enige mogelijke sociale orde. Zelfs op een onbewoond eiland, een enclave buiten de dialectiek van de geschiedenis, beslaat het de volledige ideologische horizon. Östlunds wereld – waarin de spelers van plaats wisselen, maar het spel hetzelfde blijft – visualiseert het liberale en antirevolutionaire argument dat de revolutie van het proletariaat onvermijdelijk uitmondt in een voortzetting van de uitbuiting van een onderdrukte bourgeoisie door een wraakzuchtige arbeidersklasse.

About D’Est by Chantal Akerman

D’Est – a film, a video installation. Between cinema and museum, between projection in time and distribution in space, between celluloid and electronic image. But also between two cultures, that of film and that of visual arts – between two ways of asking the question of the image: in film the question of the right image, in the museum the question of the impossible depiction.

Over D’Est van Chantal Akerman

D’Est – een film, een video-installatie. Tussen bioskoop en museum, tussen projectie in de tijd en distributie in de ruimte, tussen pellicule en elektronisch beeld. Maar ook tussen twee culturen, die van de film en die van de plastische kunsten - tussen twee manieren om de vraag van het beeld te stellen: in film de vraag naar het juiste beeld, in het museum de vraag van de onmogelijke afbeelding.

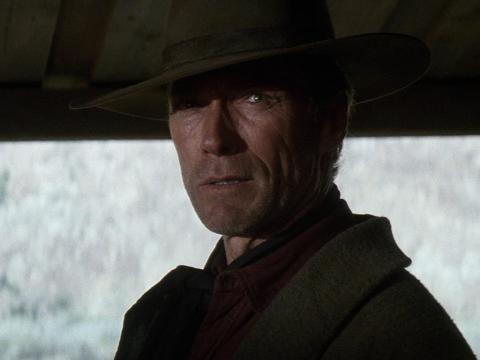

Unforgiven by Clint Eastwood

Eastwood has been one of my favourite film characters for many years: on screen and behind the camera, he has built his meditation on society around his highly stylised image. With his limits as a character actor, he does not expand his register to psychological complexity or extremity. (He’s no De Niro.) He incarnates an ideal for the male psyche: lonely, autonomous, definitively freed from the mother, withdrawn from any question, from any cry of distress. Within the script and the images, this dull, nearly mineral, fully sterile mass nevertheless becomes a wondrous sound box for the romance of unexpressed emotions. The eternally adolescent boy with his chaste, timid and excessive but vague desire.

Unforgiven van Clint Eastwood

Eastwood is sinds vele jaren een van mijn favoriete filmpersonages: op het scherm en achter de camera heeft hij de meditatie over de maatschappij opgehangen aan zijn uiterst gestileerde imago. In zijn beperktheid als karakteracteur breidt hij zijn register niet uit naar psychologische complexiteit of extremiteit. (Hij is geen De Niro.) Hij incarneert een ideaal voor de mannelijke psyche: eenzaam, autonoom, definitief bevrijd van de moeder, onttrokken aan elke vraag, elke noodkreet. Binnen het script en de beelden resoneert deze matte, bijna minerale, volledig steriele massa nochtans als een wonderlijke klankkast voor de romantiek van het onuitgedrukte gevoel. De eeuwig adolescente jongen: met een kuis, timide en mateloos, zij het onbestemd verlangen.

The One-Sided Genius of Orson Welles

The most disappointing thing about Welles – which is confirmed by Othello – is the lack of sensuality. No morbid or sentimental emotion whatsoever can be read from the screen. Jealousy and lust are cloaked in compositions, lighting and scenery; they are never made visible in the body. There is more eroticism in one shot by Straub or Bresson (surely not the most obvious ones in the field) than in an entire Welles film!

Het eenzijdige genie van Orson Welles

Het meest teleurstellende in Welles – Othello bevestigt dat – is het gebrek aan sensualiteit. Geen enkele morbide of sentimentele emotie is van het scherm af te lezen. Jaloezie en lust zijn in composities, licht en decor verpakt; nooit in het lichaam zichtbaar gemaakt. Er zit meer erotiek in één plan van Straub of Bresson (toch niet de meest vanzelfsprekende betreders van dit gebied) dan in een hele film van Welles!

Over Max Ophüls Le plaisir

Beelden overgoten met licht; flarden muziek, half gezongen, half geneuried, vanuit de verte. Zomerjaponnen temidden van korenbloemen. Wolken over de hemel. Enkele toetsen en Ophüls (en Monet) schildert het Franse landschap zoals het in de negentiende eeuw reeds vol heimwee benaderd wordt, waarvan de laatste resten reeds met een teder gevoel bekeken worden. Bij Monet reeds heimwee naar wat op het punt staat te verdwijnen, in feite reeds aan het verdwijnen is. Bij Ophüls, twintigste eeuwse cineast van de negentiende eeuw, eigenlijk een dubbel heimwee: heimwee naar het soort heimwee dat Monet kende een kleine eeuw vroeger.

Mijn bespreking van Une chambre en ville is een non-recensie. Zeker in het geval van een bewonderde filmmaker schreef ik niet graag in negatieve bewoordingen. Dat Demy’s eigenheid als filmmaker verkrampt wanneer hij zich aan ambitieuze producties waagt, mag duidelijk zijn. Tederheid kun je moeilijk beoefenen, tevoorschijn brengen als er uitvoerig moet worden gepland. Begrijpelijk, niet? Een musical, ook zoals Demy die beoefent, improviseert men niet. Draait men niet met de linkerhand!

On France by Bruno Dumont

The parable is dissolved, creating a space in which the figure of a journalist is performed “with different modulations”, like in a poem. The film does not appear to have anything to tell us, offering a topographical exploration of the empty media landscape. In this text, we explore this view and the ways in which Bruno Dumont has placed his characters in it.

Over France van Bruno Dumont

De parabel wordt ontbonden en er ontstaat een ruimte waarin de figuur van een journaliste “in verschillende variaties” wordt opgevoerd, zoals in een gedicht. De film blijkt niets te willen vertellen en biedt ons een topografische verkenning van het lege medialandschap. In deze tekst bekijken we dit vergezicht en de manieren waarop Bruno Dumont zijn personages daarin heeft geplaatst.

Over de films van Josef von Sternberg

De Kuyper typeert Von Sternberg als een “paradoxale filmmaker”, die zich op extreme wijze leek te onderwerpen aan alle clichés van Hollywood en er tegelijkertijd een démasqué van wist te bewerkstelligen. Naar aanleiding van de herpublicatie op Sabzian voorziet De Kuyper deze tekst van een nieuw commentaar. “Abstraheren of verfremden blijft een veelzeggend begrip. Wat in de context van het toenmalige Hollywood zowel het realisme als de psychologie, waar elke Hollywood-film toch op steunde, ondermijnde.”

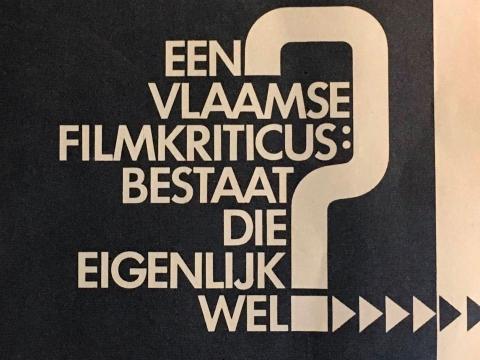

We doen wel alsof we alles hebben zoals onze buren (ook filmkritiek, die zichzelf erg goed vindt!) en misschien merkt de lezer of toeschouwer, die de situatie buiten onze grenzen niet zo goed kent, het niet eens, maar wie de wankele onderbouw kent, schrikt zich dood: cultuur wordt bij ons altijd op schaamteloze wijze onderbetaald; eigenlijk meent men bij ons dat, wie zich daar mee bezighoudt, eigenlijk zou moeten bedanken.

Monoforme

J’ai découvert le concept de Monoforme en 2003, dans une déclaration en ligne de Peter Watkins. À peu près à la même époque, j’ai vu son film sur la paix mondiale, The Journey (1987) qui constitue, selon moi, sa critique la plus claire de la Monoforme, une critique par l’exemple. Depuis, la remise en question de la Monoforme de Watkins, ainsi que ses propositions pour une réforme des mass media sont devenues pour moi un point de repère constant.

Monoform

I first encountered the concept of the Monoform in 2003 in an online statement. Around the same time, I saw Peter Watkins’s global peace film The Journey (1987). To me it remains his clearest critique of the Monoform by example. Since then, his questioning of the Monoform and his proposals for a reform of mass media have been a constant orientation point.

Monovorm

Ik kwam het Monovorm-concept voor het eerst tegen in 2003, in een online statement. Rond dezelfde tijd zag ik Peter Watkins’ wereldvredefilm The Journey (1987). Voor mij blijft deze film het duidelijkste voorbeeld van zijn kritiek op de Monovorm. Zijn vraagtekens bij de Monovorm en zijn voorstellen voor een hervorming van de massamedia zijn sindsdien een vast oriëntatiepunt.

On Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers

The dance is perceptibly preceded by a period of preparation. The dance itself, however perfect in the moment, is a culmination; it is there, gloriously in the now (only in the now). And the higher the technicity of the performance, the more intense our sense of the fragility of that performance, of its uniqueness. But if virtuosity feels inhuman, perfection feels fragile and melancholic. Anyhow, perfection is closure.

Over Fred Astaire en Ginger Rogers

De dans zelf, hoe perfect ook in het moment, is een culminatiepunt; het is er, glorieus in het nu (alleen maar in het nu). En hoe zwaarder de techniciteit van de uitvoering, hoe intenser ons besef van de fragiliteit van die uitvoering, van haar uniciteit. Maar als de virtuositeit iets onmenselijks heeft, dan heeft de perfectie iets breekbaars en weemoedigs. Perfectie is hoe dan ook afsluiten.

Didi-Huberman over Pasolini, ondanks alles

Daarover gaat het bij Pasolini: over de verschillen in het meervoudige. Niet over het enkelvoudige, eenduidige, beeld van het volk of het land, maar over de afwijkingen, de dialecten, het jargon, de woordspelletjes die hem als student al aantrekken in het werk van Dante als dichter van de aardse passies. Wat hem aantrekt is niet het grote verenigende licht, maar al die ontelbare, onvoorspelbare lichtjes: mensen als vuurvliegjes.

Seeing With Photographic Devices

Neorealist films did not seem more realistic because of the masses, the common people, the everyday life. The bourgeois-novel individuals and their psychological analysis are redundant because stories no longer need to be made convincingly plausible. But the old relationship is not merely reversed; the documentary does not gain the upper hand at the expense of the narrative. Rossellini neither relies on the fantastic coincidences of surrealist aesthetics, nor does he leave everything to devices, as cinéma vérité later did. His gaze and that of the camera are combined. A new reality only comes into view through a new way of perceiving.

Over Soy libre (Laure Portier, 2021)

Soy libre overstijgt het louter biografische. Het concrete leven van Arnaud krijgt een zinderende abstractie doordat het ingeschreven wordt in een geschiedenis. Soy libre is in die zin een klassieke vertelling, een hedendaagse levenskroniek die doet denken aan het werk van John Ford. Zoals de films van de Amerikaanse filmmaker laten zien, wordt veel van het menselijke weerwerk bepaald door de maatschappelijke omgeving. Als een gids door een woelige wereld zoekt Arnaud een antwoord op de vraag wat het leven dan de moeite waard maakt.

Beyond the terminal station at the edge of the Roman campagna, an arterial road begins, the Via Tuscolana. To the right, a film school; to the left, the walled film city Cinecittà. I looked at those great European film studios for two years but they did not stir my imagination one bit.

Voorbij het eindstation aan de rand van de Romeinse Campagna begint een uitvalsweg, de Via Tuscolana. Rechts een filmschool, links, ommuurd, de filmstad Cinecittà. Twee jaar lang zag ik daar die grote Europese filmstudio's liggen, maar ze stimuleerden mijn verbeelding geen ogenblik.

Renoir: documentarian of illusion, realist of light comedy. He distrusted creativity’s desire to rule but instead practised creativity that creates possibilities. Whoever wants to rule, must focus the field on one dominant point and neutralise all other solidarities and affinities. Similarly, whoever wants to rule the audience for the duration of a film: focus and concentrate all energy on one point! (Fear is the best strategy to do so.)

Renoir: documentarist van de illusie, realist van de lichte komedie. Hij wantrouwde de creativiteit die wou heersen, maar beoefende daarentegen de creativiteit die mogelijkheden schept. Wie wil beheersen, moet het veld focaliseren op één dominant punt, alle andere solidariteiten en verwantschappen moet hij neutraliseren. Zo ook wie voor de duur van een film over het publiek wil heersen: focaliseer en bundel alle energie op één punt! (Angst is de beste strategie daartoe.)

Introduction (2021) et Juste sous vos yeux (2021) d’Hong Sang-soo

À l’injonction du « il faut avoir vécu pour bien jouer » (Introduction), Juste sous vos yeux oppose le « vivre sans jouer ». À l’interrogation : « ma vie a-t-elle déjà réellement commencé ? » (Introduction), Juste sous vos yeux oppose une autre angoisse : « cette vie est-elle déjà finie ? ». Ces deux extrêmes ne cessent de se renvoyer la balle. Comme deux miroirs que l’on placerait l’un en face de l’autre, ces deux films ne cessent de se renvoyer de troublantes résonances obliques. C’est la grâce de Hong Sang-soo que de faire naître un vertige d’interrogations existentielles dans l’intervalle entre ses films. Pour autant, ce que nous voyons dans ses films, c’est un pur présent, aux teintes toujours renouvelées, qui nous dit que l’essentiel est toujours devant : devant la vie à venir, comme devant nos yeux.

Introduction (2021) en In Front of Your Face (2021) van Hong Sang-soo

Tegenover het gebod “je moet geleefd hebben om goed te kunnen spelen” uit Introduction stelt In Front of Your Face het “leven zonder te spelen”. Tegenover de vraag “is mijn leven al begonnen?” uit Introduction stelt In Front of Your Face een andere angst: “Is dit leven al voorbij?” Die twee uitersten spelen elkaar constant de bal terug. Als twee frontale spiegels blijven de twee films elkaar verontrustende echo’s toespelen. Het is Hong Sang-soo’s gave om tussen zijn films een duizelingwekkende reeks existentiële vragen op te roepen. Daarom is wat we in zijn films zien een zuiver heden, in steeds nieuwe tinten, dat ons vertelt dat het essentiële altijd voor ons ligt: zowel voor het leven dat komt als voor onze ogen.

Introduction (2021) and In Front of Your Face (2021) by Hong Sang-soo

Against the injunction that “one must have lived to act justly” (Introduction), In Front of Your Face posits a “living without acting”. Against the question, “Has my life already begun?” (Introduction), one finds a different fear: “Is this life already over?” The two extremes constantly throw the ball back to each other. Like two mirrors placed opposite one another, the two films keep reflecting distortive resonances. It is Hong Sang-soo’s gift to raise a dizzying array of existential questions in between his films. But what we see in his films is a pure present, with ever-renewing colours, informing us that the essential is always in front of us: both for the life to come and the life right before our eyes.

A Conversation with Helga Fanderl

“I discovered filmmaking by chance. Through an early short film that I thought was successful, I found out what I could create without language, only with the language of a small silent Super 8 film. This was overwhelming. I filmed quite a lot, and I realized that my approach to the world was very visual, although language still matters to me: I studied languages and love foreign languages, I lived abroad, I love poetry. But it was something else to create purely visual films.”

中国独立电影现状

中国电影在30 年前出现了独立电影,慢慢的独立电影变成中国年轻导演电影创作的主要途径,大量独立电影作品也改变了中国电影整体的创作生态,使中国原先单一国家体制内电影制作限制有所改变,这些好的发展也曾经给很多电影人非常大的信心,对未来中国电影报着很大希望。但是,这几年中国政治的变化和疫情的影响,使中国独立电影基本上创作和拍摄全面终止,只有很少的导演还在坚持独立电影创作。

The State of Chinese Independent Film

After independent films first appeared on the Chinese cinematic landscape three decades ago, they gradually became the method of choice among young Chinese filmmakers. The large number of Chinese independent films also transformed the broader creative ecosystem by bending the constraints of China’s once-monolithic state-controlled film system. These positive developments gave many filmmakers great optimism and confidence in the future of Chinese film. In recent years, however, domestic political changes and the effects of the pandemic have essentially put a halt to the development and production of independent films in China. There are very few directors left who continue to create independent films.

De huidige staat van de Chinese onafhankelijke film

Drie decennia geleden verscheen de onafhankelijke film voor het eerst in het Chinese filmlandschap, om daarna geleidelijk aan de creatieve methode bij uitstek te worden van jonge Chinese filmmakers. Het grote aantal onafhankelijke films transformeerde de ruimere creatieve context door de beperkingen van het zo specifieke, door de staat gecontroleerde Chinese filmsysteem naar hun hand te zetten. Door deze positieve ontwikkelingen keken veel filmmakers met optimisme en vertrouwen naar de toekomst van de Chinese film. Binnenlandse politieke veranderingen en de gevolgen van de pandemie hebben de ontwikkeling en productie van onafhankelijke films in China de voorbije jaren echter vrijwel tot stilstand gebracht, zodat vandaag nog slechts een handvol filmmakers doorgaat met het maken van onafhankelijke films.

L’état du cinéma indépendant chinois aujourd’hui

Le cinéma indépendant a fait son apparition en Chine il y a 30 ans et s’est progressivement imposé comme la voie principale des jeunes cinéastes pour réaliser des films. Beaucoup de ces œuvres cinématographiques indépendantes ont transformé l’environnement créatif général du cinéma en Chine et ont fait évoluer les contraintes de production au sein de ce système si particulier qu’est le cinéma officiel chinois. Ces développements positifs ont donné confiance à de nombreux cinéastes et ont porté de grands espoirs pour l’avenir du cinéma chinois. Pourtant, l’évolution politique de la Chine et l’impact de l’épidémie de Covid de ces dernières années ont pratiquement mis à l’arrêt la création et le tournage de films indépendants chinois, si bien que seule une poignée de réalisateurs persévèrent encore dans cette voie aujourd’hui.

A Critical Reflection on Wang Bing’s cinema

Wang Bing explores how people’s ideals and dreams relate to reality, how cinema makes it possible to affectively rethink one’s subjective relationship to society. Wang belongs to a generation of Chinese filmmakers who since the 1990s, but exponentially since the turn of the century thanks to the introduction of lightweight affordable DV cameras, document society from the bottom up, independently, (mostly) outside of the state-sanctioned film industry.

For me, film has long been first and foremost the bizarre art of showing and looking at bodies, the art of inventing hundreds of ways in which emotions and consciousness become bodily visible. Film is narration through bodies rather than images. Images are at the service of those bodies, are draped around those bodies, filled with bodies, carried by bodies.

Sabzian publiceert de eerste Nederlandstalige vertalingen van enkele teksten van Fernand Deligny. Hij schreef verschillende teksten over camereren, een werkwoord dat zich onderscheidt van wat we doorgaans filmen noemen. Via dit neologisme opende hij een uniek perspectief op de camera. Deligny: “Wat een buitenkans om vrijuit te kunnen camereren net zoals een kind – of een idioot – kiezelsteentjes gooit in het water, ik wil zeggen de gemeenschappelijke ontroering.”

“Ryuji and I are from different countries, but when making movies together, when making a life together, our differences allow us to view people and situations from different perspectives. And so we decided to use ten months to shoot Stonewalling, and use the perspective of time and its changes to help us find the character and film’s essence.”

André Delvaux, de vader van de Belgische cinema die prijzen en gouden medailles kreeg op tal van festivals, was een cultureel ambassadeur voor zijn land, dat hij wereldwijd heeft doen schitteren. Zijn diepe band met de kunsten, waarvan hij een originele synthese biedt, maakt van hem een dichter met een onvergetelijk beeldende stijl.

André Delvaux, père du cinéma belge, primé dans de nombreux festivals dont il rapporte des médailles en or, fut un ambassadeur culturel de son pays qu’il a fait rayonner dans le monde. Dans ses rapports profonds avec les arts, dont il offre une synthèse originale, il demeure le poète mémorable d’un style imagé.

Aan de uitnodiging om – als auteur van de roman (aan scenario en film heb ik niet meegewerkt) – mijn mening neer te schrijven over André Delvaux’ verfilming van mijn Man die zijn haar kort liet knippen, voldoe ik tegelijk graag en ongraag. Graag om hulde en dank te betuigen aan Delvaux, ongraag omdat het altijd kies is zich te uiten omtrent een aangelegenheid waarin men persoonlijk betrokken is.

Watching and appreciating a film starting from its mise-en-scène is like adding a fourth dimension to plot and characters. Behind the characters their maker appears, behind the plot the process of the mise-en-scène appears.

Nightmare of a Divided Self and Nation

Displacement in relation to language stands at the center of André Delvaux’s troubling and troubled Un soir, un train (1968) – so precisely and so relentlessly that even the disquiet created by the collision of disparate nouns in the poetic title (a time and a place/thing/vehicle, improbably yoked together like a chance meeting between a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissecting table) arguably becomes lost or at least diluted in its English translation.

Film, at a time when there was no television, did not only live on the screen in the theatre. Film lived all the time, its many fragments and images colouring and flooding everyday life. It lived in conversations that – about novels read as well – filled me as a child with frustration and longing. All too often I had to make do with mere snippets.

Film, in een tijd waar er nog geen televisie bestond, leefde niet enkel op het scherm, daar in een zaal. Film leefde voortdurend als zovele flarden en beelden die het dagelijkse leven kleurden en overspoelden. Ook in gesprekken die – overigens ook over gelezen romans – het kind dat ik was met frustratie en verlangen vervulde. Ik moest het voorlopig maar al te vaak met snippers doen.